February 27, 2013, Wednesday — Last

“A life which belongs totally to the work of God”

“I will no longer bear the authority of the office for the government of the Church, but in the service of prayer rest, so to speak, in the yard of St. Peter. St. Benedict, whose name I bear as Pope, will be a great example for me in this. He showed us the way to a life which, active or passive, belongs wholly to the work of God.” (“Non porto più la potestà dell’officio per il governo della Chiesa, ma nel servizio della preghiera resto, per così dire, nel recinto di san Pietro. San Benedetto, il cui nome porto da Papa, mi sarà di grande esempio in questo. Egli ci ha mostrato la via per una vita, che, attiva o passiva, appartiene totalmente all’opera di Dio.”) —Pope Benedict XVI today in St. Peter’s Square, in his final public audience as Pope

Last General Audience

Today was the next-to-last day of Pope Benedict XVI’s papacy.

Today he gave his final public address as Pope before an estimated 200,000 people in a packed St. Peter’s Square, under an unusually warm February sun.

It was a beautiful day.

One of the signs held up in the piazza said, “Elect Benedict again!”

The cardinals may not be willing to do this, but the sign expressed a widespread feeling that there isn’t a better choice right now, among the cardinals or in the whole world, to be the Bishop of Rome and successor of Peter.

And yet, the central point of the Pope’s remarks today was that he himself — the reigning pontiff, the one who holds the power of the keys to “bind and loose,” the one who wears “the ring of the fisherman” and wields its authority — has decided differently.

He has decided that someone else can be, or can function, as a better Pope, in the particular circumstances that now exist, given his age, his health, and given everything he knows about his own condition and the needs of the Church.

And so, tomorrow evening, after a morning meeting in Rome with his cardinals, who are gathering from around the world — only 65 of them were present this morning — Pope Benedict will fly by helicopter to Castel Gandolfo, a short distance outside of Rome, and the cardinals will undertake to meet in conclave and elect a new Pope.

(Note: The word “conclave” means “with a key” — “con” is the Italian for the Latin “cum,” “with,” and “clave” is from the Latin word “clavis,” “a key”; in the ablative form “clavis” becomes “clave,” and that form is carried over directly into English; so “conclave” means “a gathering in a room locked with a key,” or, “a gathering in secret, with no outsiders present to influence those who are meeting, all outsiders being kept outside a door locked with a key, until those who are meeting end their deliberations.”)

Uncharted waters

All of this puts the Roman Catholic Church in uncharted waters, of course.

Everyone is aware of the questions:

Will the cardinals choose as the next Pope someone “in line” with Pope Benedict, or someone who will be dramatically different?

Then, will the two men speak together? Rarely? Often? Daily? Will the new Pope ask the old Pope for advice?

And then, does Benedict’s decision to resign weaken the idea, and the reality, of the papal office? Until a few days ago, the papacy has always been considered an office (but also more than an office, a charism, a special service accompanied by a special grace, the grace of infallibility) to be held until the moment of death. Was that thinking incorrect? Was it incomplete?

And, does the resignation decision have ecumenical implications? Does it open the way to better relations with the Orthodox, and with some Protestants, for whom the Roman papacy, both in its theological claims and in its historical manner of functioning, has been seen as a “stumbling block” on the path toward possible Christian unity?

And, will the new Pope make dramatic changes in the Roman Curia, changes Pope Benedict might have made, or might have wished to have made, but was too old or tired to make, or for some other reason impeded from making?

Many questions… and there are many more.

But today was not a time for questions.

Today was time for a morning of peace, in the warm February sun.

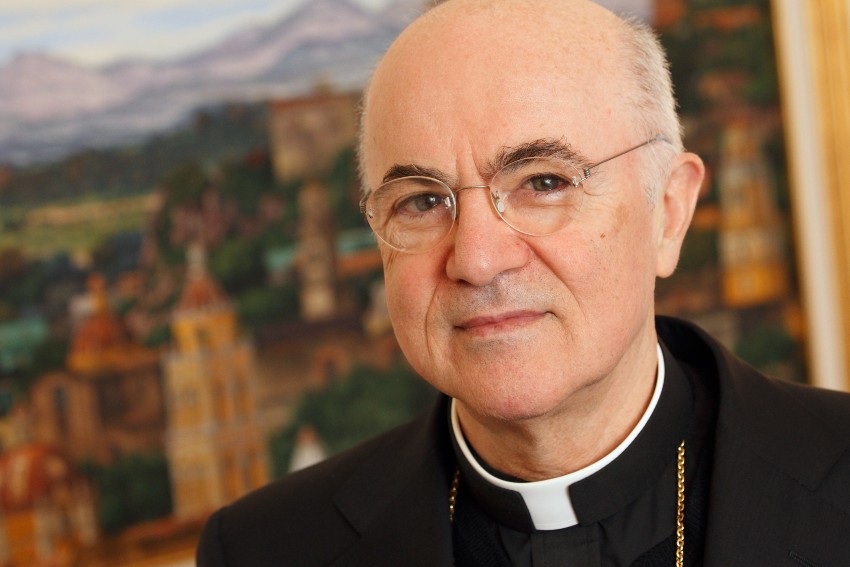

The Pope drove into the Square in his Popemobile, accompanied by his personal secretary, Archbishop Georg Gaenswein (photo).

It took nearly half an hour for the Pope to reach the front of the Square and take his chair on the sagrato, that consecrated area of the piazza which is raised above the level of the main square, just in front of the facade of the basilica.

On one side sat cardinals and archbishops — as I said, I counted 65 cardinals present. On the other side, the diplomatic corps, representatives of governments from around the world.

The Pope then spoke, gave his teaching in Italian, and at the end of his speaking, after greeting the crowd in several foreign languages, all that vast throng prayed the Our Father, singing the prayer in Latin.

The Pope then rode in his popemobile out of the square, and the 348th, and last, papal general office of this nearly 8-year pontificate, was over.

A “double helix” linking Peter to Peter…

There was no dramatic announcement. The Pope did not say anything that from a “news” perspective was extraordinary.

Or did he?

Upon reflection, what Benedict said today had quite profound importance: what he said seemed to render his decision to resign, in some way, “irreversible.”

That is, he seemed to make the idea of a pontiff resigning part of the ordinary landscape of the papacy.

This is a remarkable shift, considering that 16 days ago, on February 11, when he announced his decision to resign, the idea of a papal resignation was almost unthinkable — had not in fact been thought for 700 years, and had not been thought in this precise way ever. (The circumstances of previous papal resignations were all quite different.)

In this sense, what Benedict did by resigning on February 11, and what he did today during his General Audience by “codifying” that decision, together make up the greatest single revolutionary act of his pontificate, and of his life.

Here is the relevant part of the talk today, which I will try to analyze paragraph by paragraph.

“In recent months, I felt that my strength had decreased, and I asked God earnestly in prayer to enlighten me with his light to make me take the right decision not for my sake, but for the good of the Church.” (“In questi ultimi mesi, ho sentito che le mie forze erano diminuite, e ho chiesto a Dio con insistenza, nella preghiera, di illuminarmi con la sua luce per farmi prendere la decisione più giusta non per il mio bene, ma per il bene della Chiesa.”)

Here the Pope introduces the subject of his resignation.

He sets it against the background of his declining strength. He does not say it, but this includes his fall in the night where he hit his head causing bleeding last March in Mexico; his declining sight in one eye; his inability to sleep at night; his exhaustion at the end of a long day of appearances; the looming burden of the multiple, long liturgies at Easter; and the looming burden of World Youth Day this summer in Brazil, though his doctor a few months ago told him that he should not take any more international flights for health reasons.

But despite all of this, he is not interested in his own health, his own life, but in what would be good for the Church.

“I have taken this step in full awareness of its severity and also newness, but with a deep peace of mind. Loving the Church also means having the courage to make difficult choices, suffering (in the process of deciding), having always before one the good of the Church and not oneself.” (“Ho fatto questo passo nella piena consapevolezza della sua gravità e anche novità, ma con una profonda serenità d’animo. Amare la Chiesa significa anche avere il coraggio di fare scelte difficili, sofferte, avendo sempre davanti il bene della Chiesa e non se stessi.”)

“Allow me to return once again to April 19, 2005. The severity of the decision was precisely in the fact that from that moment on I had been given my task to carry out always and forever by the Lord.” (“Qui permettetemi di tornare ancora una volta al 19 aprile 2005. La gravità della decisione è stata proprio anche nel fatto che da quel momento in poi ero impegnato sempre e per sempre dal Signore.”)

Here is the place where Benedict states that his election to the papacy was something, “always” and “forever.” And “forever” would seem to exclude any sort of resignation.

“Always – he who assumes the Petrine ministry no longer has any privacy…” (“Sempre – chi assume il ministero petrino non ha più alcuna privacy…”)

He is repeating the word “always.” This is clearly what was on his mind as he wrestled with his decision. He is letting us see inside his decision-making process. We can almost see him saying to himself: “Always… but I am too weak… always… but I am unable to do what I must do, for the Church’s good… Yet I am committed, and made a commitment, to continue always…”

“He always and totally belongs to everyone, the entire Church. His life is, so to speak, totally deprived of the private sphere. I experienced, and I am experiencing it right now, that one receives life precisely when one gives it. I said before that a lot of people who love the Lord also love the Successor of Saint Peter and are very fond of him. I’ve said before that the Pope has truly brothers and sisters, sons and daughters all over the world, and that he feels in the embrace of their communion, because it no longer belongs to himself, instead he belongs to everyone, everywhere. (“Appartiene sempre e totalmente a tutti, a tutta la Chiesa. Alla sua vita viene, per così dire, totalmente tolta la dimensione privata. Ho potuto sperimentare, e lo sperimento precisamente ora, che uno riceve la vita proprio quando la dona. Prima ho detto che molte persone che amano il Signore amano anche il Successore di san Pietro e sono affezionate a lui; che il Papa ha veramente fratelli e sorelle, figli e figlie in tutto il mondo, e che si sente al sicuro nell’abbraccio della loro comunione; perché non appartiene più a se stesso, appartiene a tutti e tutti appartengono a lui.”)

Here the Pope is speaking about how it is to be Pope, how one loses one’s private life, gives it up entirely, but then receives back much in return.

Then he comes back to the question of the resignation:

“The ‘always’ is also a ‘forever’ – there is no return to the private [life]. My decision to forgo the exercise of active ministry does not revoke this fact. I am not returning to private life, to a life of travel, meetings, receptions, conferences, and so on. I am not abandoning the cross, but I am remaining at the foot of the Crucified Lord.” (“Il ‘sempre’ è anche un ‘per sempre’ — non c’è più un ritornare nel privato. La mia decisione di rinunciare all’esercizio attivo del ministero, non revoca questo. Non ritorno alla vita privata, a una vita di viaggi, incontri, ricevimenti, conferenze eccetera. Non abbandono la croce, ma resto in modo nuovo presso il Signore Crocifisso.”)

Here the Pope is emphasizing that his resignation does not contradict the “always,” meaning, this resignation is not a normal one, it isn’t a stepping down from a public office to a private life.

Nor is it a “coming down off of the cross,” as one cardinal from Poland who had been close to Pope John Paul II at first said he was doing. Benedict flatly denies this is the case.

So we know from these lines that he is not simply “resigning” as we would think in the ordinary course of things. Something else is happening here. But what?

“I will no longer bear the authority of the office for the government of the Church, but in the service of prayer I stay, so to speak, in the yard of St. Peter.” (“Non porto più la potestà dell’officio per il governo della Chiesa, ma nel servizio della preghiera resto, per così dire, nel recinto di san Pietro.”)

This is the phrase I find fascinating. Clearly, he says he will no longer “bear the authority of the office” but then he adds “for the government of the Church.”

And then he adds a “but” — “but in the service of prayer, I stay…”

He is leaving, but he is staying.

He is leaving the authority of government.

He is staying in the service of prayer.

The word “recinto” is a bit strange and hard to translate. It means “enclosure,” “paddock,” “pen,” “surrounding wall.” A “recinto” is therefore a closed-in area, an area quite defined, an area created to enclose things and keep them safe.

So he is saying he is staying within the area etablished and closed in by St. Peter.

Though it is not entirely clear, it certainly means he continues to have some sort of connection to St. Peter and to Peter’s ministry, to “care for the flock,” to “love the lambs” the Lord asked Peter, and Benedict, to care for.

“St. Benedict, whose name I carry as Pope, will be for me a great example in this. He showed us the way to a life which, active or passive, belongs wholly to the work of God.” (“San Benedetto, il cui nome porto da Papa, mi sarà di grande esempio in questo. Egli ci ha mostrato la via per una vita, che, attiva o passiva, appartiene totalmente all’opera di Dio.”)

This is a key phrase. Benedict is named “Benedict.” As an old man, at age 85, faced with infirmities and many problems requiring great energy to resolve, he is trying to understand his role, his path. He thinks back to St. Benedict, his namesake. St. Benedict committed “all” to the Lord, to the work of the Lord. But that “all” had two parts: to pray, and to work. Orare, e laborare. First, pray, then, work. Ora, et labora.

Pope Benedict feels he is too weak to work. Yet he can still pray.

So, in this motto of St. Benedict, he finds that he can do one half of his task, while being unable to do the other.

So, he will do one part, even if he cannot do the other.

In this sense, he will continue… And that is what he says in these next lines…

“I thank each and everyone for your respect and understanding with which you have welcomed this important decision. I will continue to accompany the journey of the Church through prayer and reflection, with that dedication to the Lord and to his Spouse with which I have tried to live until now every day and which I want to live always. I ask you to remember me before God, and above all to pray for the Cardinals, who are called to such an important task, and the new Successor of Peter: may the Lord accompany him with the light and the power of his Spirit.” (“Ringrazio tutti e ciascuno anche per il rispetto e la comprensione con cui avete accolto questa decisione così importante. Io continuerò ad accompagnare il cammino della Chiesa con la preghiera e la riflessione, con quella dedizione al Signore e alla sua Sposa che ho cercato di vivere fino ad ora ogni giorno e che voglio vivere sempre. Vi chiedo di ricordarmi davanti a Dio, e soprattutto di pregare per i Cardinali, chiamati ad un compito così rilevante, e per il nuovo Successore dell’Apostolo Pietro: il Signore lo accompagni con la luce e la forza del suo Spirito.”)

Thus, Benedict today said his decision to resign was arrived at in deep prayer, was desired by God, was decided “for the good of the Church.” Implicitly, this means the decision that may again be taken in the future by another Pope.

Pope Benedict has, in this way, made a radical, dramatic change in one of the world’s oldest, most unchanging, global institutions, a change both in how it functions, and also in how its leadership is conceived.

In these words today, the Pope is explaining what an “Emeritus Pope” is, theologically and ecclesially, and what the role of such a Pope is, or may be, in the Church.

And he did this calmly, without fanfare, as if it were something completely normal.

Have even the cardinals understood the magnitude of the change the Pope’s decision has brought?

From the perspective of Church history, and from the perspective of Catholic theology on the Petrine office, the Pope’s decision goes far beyond anything connected to administrative decisions, or to “lobbies” in the Roman Curia (of whatever sort…), or to struggles for power and influence in Rome or throughout the world.

These there have always been.

The Pope’s decision is new.

Vacant and not vacant…

We are now less than 24 hours away from a “sede vacante,” an empty See of Peter.

A vacant papal throne.

And yet, if Benedict’s words of this morning mean anything — and I acknowledge that my way of interpreting the situation may seem quite mysterious and strange — they also mean that the See is not totally vacant.

They mean that, in some mysterious way, since Pope Benedict is still alive, and still committed to the office he was called to in 2005, and still committed to living inside Vatican City, though entirely hidden from the world, there is a sort of continuity, there is something of the papal office that continues, a strand of vibrant, spiritual continuity, even as he publicly sets the main part of that office down.

I hesitate to formulate it in this way, as it may seem that I am proposing that there are two Popes, or soon could be. This is not the case.

Rather, there are emerging two ways of exercising the Petrine office, one of action, the other of prayer and contemplation.

In this interpretation, the new Pope will take up the active office, while the “emeritus Pope” continues that aspect of the office which is of prayer and contemplation.

This is what Benedict seems to be saying — disconcerting, perplexing, confusing as it may seem.

Joseph Ratzinger made clear this morning that he will never again be simply Joseph Ratzinger, a private citizen. That is excluded. He made that quite clear today.

He will not be a like a president who resigns and moves out of the White House and takes up writing his memoirs, as an ordinary citizen again.

So, he will, in some sense — in some sense that may require some heavy lifting by theologians to clarify — remain “Peter.” Peter living a hidden life in the gardens of the Vatican, in the city of Rome. Petrus Romanus.

On the day he was elected, April 19, 2009, he took the new name, Benedict, leaving behind his baptismal name, Joseph.

And on the day of his crowning as Pope, he took on the name “Peter,” promising at that moment to be “Pope forever” (“Papa per sempre”).

And he said this morning that he will not go back on that “forever,” even though he is resigning: “I am not returning to private life, I am remaining in the yard of St. Peter” (“Non ritorno alla vita privata, resto nel recinto di San Pietro”).

Instead, he said he plans to emulate St. Benedict — again, his papal name is Benedict — in leading a life dedicated completely to God.

This space, this yard, this “recinto” where Benedict will remain, is not simply a physical space, the former nun’s convent in Vatican City, in the gardens.

It is actually a spiritual space in the structure of the Church herself, a place “near Peter,” a space in which an emeritus Pope, even if “hidden from the world,” continues to live and have a role, like one more link in the chain of apostolic succession.

One might almost say it like this: (1) the new Pope, who will be elected in two or three or four weeks time, will be linked to all previous Popes who have died, and this is shown by the many tombs of Popes found in St. Peter’s Basilica, and by St. Peter’s tomb (which is directly under the high altar, and directly under the massive cupola of Mchelangelo); but (2) the new Pope will also be linked to one previous Pope who has not physically died, but has, in a sense, been buried “to the world,” and yet lives “in prayer,” in a convent near the basilica, though “dead to the world.”

It will be up to Pope Benedict’s successor to decide how to use this resource, how to relate to the still living Pope who has nevertheless died to the world.

Will he consult with him? Will he not see him at all? We do not know.

On Sunday, the Pope spoke in his homily about the Transfiguration of the Lord.

Today, Benedict was, in a manner of speaking, “transfigured.”

His figure is no longer that of a reigning Pope.

Nor is it that of a citizen who has stepped down from a high office. That is not at all what has happened.

Benedict has become a unique figure, not one, and not the other, not a Pope, and not a non-Pope.

He is an “emeritus Pope” who has finished his active service, but not laid down the burden of a life of service which he took upon his shoulders on the day of his election to the See of Peter.

This is something new in Church history, and like all new things, there will be a period of time before we really begin to comprehend fully what it means.

The Pope’s spokesman, Father Federico Lombardi, seemed to sense this when he spoke about this morning’s events to the press corps.

There was a climate of “profound emotion and serenity,” Lombardi said.

Then he added: “I don’t know if you were able to see, on the television monitor, the last moments of the Vatican television feed that showed a face of the Pope that was very beautiful and extremely serene, with a radiant smile.”

That “beautiful face,” that “radiant smile” suggests that Pope Benedict has “moved on.”

He is in a new place.

The old descriptions no longer suffice to descrive where he is.

It will take us time to understand better what it means.

After the audience, the Pope returned to the Apostolic Palace and received privately the president of Slovakia, Ivan Gasparovic, and the president of Bavaria, Germany, Horst Seehofer, as well as the mayor of Rome, Gianni Alemanno, and the ruling captains of the Republic of San Marino, Teodoro Lonferini e Denis Bronzetti.

Early this afternoon, Lombardi said the Pope’s serenity and joy were due to his consciousness “of having finished a good work and of having taken this decision before God and in complete accord with what the will of God was asking of him.”

Lombardi then went over a few passages from the Pope’s teaching.

Lombardi said the passage on the work of God, where the Pope referred to St. Benedict, was very important.

“Opus Dei, the work of God, what he has tried to do and what he will continue to do,” Lombardi said. “He showed us a way for a life that, active or passive, belongs totally to the work of God. Thus (the Pope was saying) my work is in the work of God.” (“Opus Dei, l’opera di Dio, quello che lui ha cercato di fare e che lui continuerà a fare. Ci ha mostrato la via per una vita che, attiva o passiva, appartiene totalmente all’opera di Dio. Quindi la mia opera è nell’opera di Dio.”)

Lombardi also told journalists that the stove to burn the ballots after each vote during the conclave has not yet been installed in the Sistine Chapel.

Tomorrow the College of Cardinals — those who are already in Rome — will meet with the Pope in the large Sala Clementina.

Cardinal Angelo Sodano, 85 (the same age as the Pope), who is the dean of the College, will give a talk of farewell to the Pope. The Pope will then have a moment to speak with each cardinal, one by one, privately.

The Pope will then leave from Vatican City by helicopter at 5 p.m. sharp.

A few minutes later, at Castel Gandolfo, Benedict will enter the papal summer palace, then come to the window and say a few words to the people of that small town. Those will be the Pope’s last public words ever.

(to be continued…)

Facebook Comments