May 27, 2017, Saturday

Universal or Particular?

The article below, by American Catholic writer Matthew Schmitz, originally published on May 22 (five days ago) in the important American journal of ideas First Things (link), is noteworthy. (The journal calls itself “America’s most influential journal of religion and public life.”)

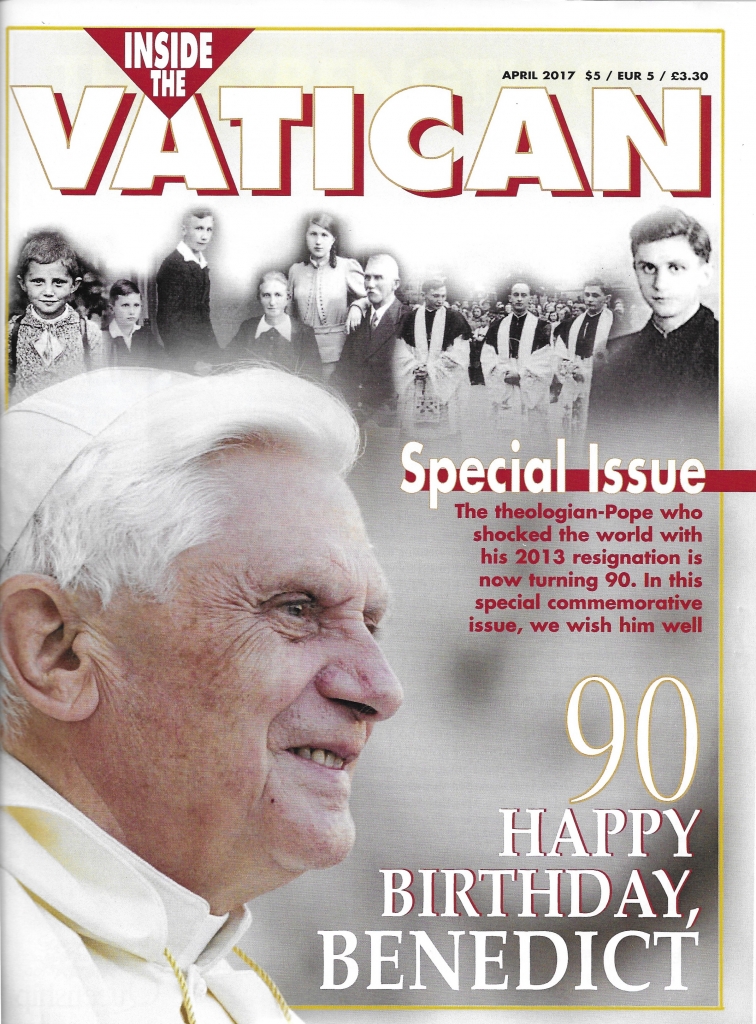

(Below, the cover of the April 2017 special commemorative issue of Inside the Vatican, on the occasion of the 90th birthday of Emeritus Pope Benedict on April 16, 2017)

It is an interesting and useful, though by no means comprehensive or exhaustive, summary of the theological debate between then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (now the 90-year-old Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI) and Cardinal Walter Kasper.

And it explains, briefly and synthetically, how that debate is in some way “reopened” in the current debate over Amoris Laetitia.

So a theological debate that was important for about two years in around the year 2000, 17 years ago, remains important today, 17 years later.

At stake? In a profound way, the identity of the Church.

And that is why this article is worth reading.

The key question the debate around the year 2000 raised — and continues to raise in 2017 — is whether the Church, in being “one” and “catholic,” can also be, without contradiction, “many” and “particular.”

Yes, or no?

To phrase the question in the opposite way: can a Church that becomes “many” and “particular” still be the “one” and “catholic” Church of the Creed.

Or… does such a Church, or Churches, become… something else.

No longer the Church of the Creed.

So it is a quite serious matter.

We know from the Creed that the four attributes of the Church are that she is “one, holy, catholic and apostolic.”

And we know that the Church, due to human frailty and human sin, can always “fall away,” in one way or another, from these four “characteristics” — dividing into many denominations rather than remaining “one”; becoming, or wishing to become, profane, idolatrous, or sinful rather than remaining steadfastly and faithfully “holy”; becoming local or national, “particular,” rather than remaining universal, “catholic”; and, via new insights and innovative theological arguments, breaking with the apostolic tradition rather than remaining firmly dependent on what the apostles taught, and not on what any other teachers or gurus of subsequent centuries have taught, in this way remaining “apostolic.”

One, holy, catholic, and apostolic.

We profess that these are the qualities or characteristics of the true Church.

And the debate between Cardinals Kasper and Ratzinger in about the year 2000 brought into question whether the Church could remain one, and catholic, or whether it could be somehow “multiple,” or “many” while still being “one” or “local” and “particular” while still being “catholic.”

The article by Schmitz notes that some Catholic theologians in the post-conciliar period (after the 1962-65 Second Vatican Council) had agreed that “doctrine might be universal and unchanging,” but went on to argue, nevertheless, that doctrines “could be bent to meet discrete pastoral realities — allowing for a liberal approach, say, in Western Europe and a more conservative one in Africa.”

Schmitz writes: “In order to guard against this idea, Pope John Paul II and Ratzinger, then head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, insisted that the universal Church was ‘a reality ontologically and temporally prior to every individual particular Church.’”

So, it was Ratzinger, evidently partly at John Paul’s behest, who argued for the “universal Church.”

And Cardinal Kasper, a leader of the theological school seeking to “bend” doctrine to meet “discrete pastoral realities,” argued for the ontological validity, for the acceptability, of something he called the “particular Church.”

Schmitz’s article notes that this debate, which seems to deal with abstract theological concepts, actually has an important role to play in other debates which seem to play a more important role in the daily lives of ordinary men and women.

And, in particular, in the matter of marriage, divorce, remarriage, and receiving the sacraments — the matter which has become so controversial in light of the Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitia, issue in April 2016, a little more than one year ago.

Schmitz notes that Ratzinger once wrote: “The basic idea of sacred history is that of gathering together, of uniting human beings in the one body of Christ, the union of human beings and through human beings of all creation with God. There is only one bride, only one body of Christ, not many brides, not many bodies.”

The point is that, because the Church is this “bride,” the Church is in some way a “nuptial” reality, and likewise, human marriage is in some way a mirror of the relationship between Christ and his bride, the Church.

That is, the debates over the two questions intertwine.

Schmitz writes of the Kasper-Ratzinger debate: “Ratzinger cited1 Corinthians, where Paul describes the unity of the Church in terms of two sacraments — communion and matrimony. Just as the two become one flesh in marriage, so in the Eucharist the many become one body. ‘For we being many are one bread, and one body: for we are all partakers of that one bread.’”

But then Kasper responded, appealing to “pastoral reality.”

Kasper, Schmitz notes, “laments that Ratzinger does not see things his way.” Kasper says: “Regrettably, Cardinal Ratzinger has approached the problem of the relationship between the universal church and local churches from a purely abstract and theoretical point of view, without taking into account concrete pastoral situations and experiences.”

Ratzinger argued during the debate with Kasper that Christian baptism is a truly trinitarian event; we are baptized not merely in but into the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

We are not made members of one of various local Christian associations, but are united with God, Ratzinger stressed.

For this reason, he argued, “Anyone baptized in the church in Berlin is always at home in the church in Rome or in New York or in Kinshasa or in Bangalore or wherever, as if he or she had been baptized there. He or she does not need to file a change-of-address form; it is one and the same Church.”

And Ratzinger taught in this way during his papacy as Pope Benedict XVI.

Schmitz notes that the theological debate between Ratzinger and Kasper over “universal Church” vs. “particular Church” drew to a close in 2001, and that, after Ratzinger then became Pope in 2005 and up until 2013, when he resigned, he emphasized the ontological importance of the concept of the Church as “universal.”

But, Schmidt argues, since the election of Pope Francis in March 2013, and Francis’ public praise of the theology of Cardinal Kasper in his very first Angelus address, the pendulum has swung back again in favor the Kasper thesis of adapting doctrine, for pastoral reasons, to the situation of different “particular” Churches.

And for this reason, Schmitz argues, there has been a theological reversal over the past four years which has not been only about marriage, divorce and remarriage, but also about the very fundamental ecclesiological question of whether the Church is “one” and “universal” or “multiple” and “particular.”

To bring about this theological reversal, it has been necessary to downplay the theological arguments of Cardinal Ratzinger-Pope Benedict in favor of the “universal” Church, and to revisit Kasper’s arguments in favor of the “particular” church.

And that is why Schmitz, or his editors, gives a rather sensationalistic title to his essay: “Burying Benedict.”

So here we are… a 17-year-old theological debate of the most “abstract” sort that ends up having a very practical effect; a debate between theologians from about the year 2000 in different journals and magazines which ends up taking on new life 17 years later at the crossroads of many of the most critical theological and pastoral debates of our present time.

For this reason, the article is well worth reading.

Clearly, Schmitz’s position is polemical. He is attacking the position of Cardinal Kasper, and, by extension, of Pope Francis. He ends his article by saying: “For better or worse, Francis now seeks to reverse Ratzinger.”

But that very phrase “for better or worse,” reveals that Schmitz is allowing space for some sort of theological response from the Francis and Kasper camp. Such a response might argue that, in some way, the positions of Ratzinger and Kasper, though seemingly so different, are not in fact incompatible. And that is precisley, it appears, what they have argied.

But is that the case?

That is the question of the moment.

So it is a continuing debate.

With that as a preamble, the publication of this article is a welcome contribution to this continuing debate in the Church, a debate which, arguably, will have to be settled, for the sake of the Church, and to avoid continued confusion among the faithful, with considerably more clarity than up to now, in the months and years ahead…

(continued below)

===========================

ONCE-IN-A-LIFETIME PILGRIMAGE

JUNE 16-25, 2017

LONDON AND OXFORD, ENGLAND

Join me in the prison cell of St. Thomas More in the Tower of London for Mass on St. Thomas More’s Feast Day, June 22! A pilgrimage in the footsteps of St. Thomas More and Blessed John Henry Newman. Don’t delay: only 2 places left!

[email protected]

+1.202.536.4555

=====================

(continued from above)

Here is the text of the Matthew Schmitz article:

BURYING BENEDICT

by Matthew Schmitz

5 . 22 . 17

First Things

Though Benedict is still living, Francis is trying to bury him. Upon his election in 2013, Francis began to pursue an agenda that Joseph Ratzinger had opposed throughout his career. A stress on the pastoral over against the doctrinal, a promotion of diverse disciplinary and doctrinal approaches in local churches, the opening of communion to the divorced and remarried—all these proposals were weighed and rejected by Ratzinger more than ten years ago in a heated debate with Walter Kasper. For better or worse, Francis now seeks to reverse Ratzinger.

The conflict began with a 1992 letter concerning “the fundamental elements that are to be considered already settled” when Catholic theologians do their work. Some theologians had suggested that while doctrine might be universal and unchanging, it could be bent to meet discrete pastoral realities—allowing for a liberal approach, say, in Western Europe and a more conservative one in Africa.

In order to guard against this idea, Pope John Paul II and Ratzinger, then head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, insisted that the universal Church was “a reality ontologically and temporally prior to every individual particular Church.” There would be no Anglican-style diversity for Catholics—not under John Paul.

Behind this seemingly academic debate about the local and universal Church stood a disagreement over communion for the divorced and remarried. In 1993, Kasper defied John Paul by proposing that individual bishops should be able to decide whether or not to give communion to the divorced and remarried. Stopping short of calling for a change in doctrine, he said that there ought to be “room for pastoral flexibility in complex, individual cases.”

In 1994, the Vatican rejected Kasper’s proposal with a letter signed by Ratzinger. “If the divorced are remarried civilly, they find themselves in a situation that objectively contravenes God’s law. Consequently, they cannot receive Holy Communion as long as this situation persists.” Kasper was not ready to back down. In a festschrift published in 1999, he criticized the Vatican’s 1992 letter and insisted on the legitimate independence of local churches.

Ratzinger responded in a personal capacity the following year. It is because of such responses that he gained his reputation as a rigid doctrinal enforcer, but this caricature is unfair. Benedict has always been a poet of the Church, a man in whose writing German Romanticism blooms into orthodoxy. We see it here in his defense of Christian unity. He describes the Church as “a love story between God and humanity” that tends toward unity. He hears the gospel as a kind of theological ninth symphony, in which all humanity is drawn together as one: “The basic idea of sacred history is that of gathering together, of uniting human beings in the one body of Christ, the union of human beings and through human beings of all creation with God. There is only one bride, only one body of Christ, not many brides, not many bodies.”

The Church is not “merely a structure that can be changed or demolished at will, which would have nothing to do with the reality of faith as such.” A “form of bodiliness belongs to the Church herself.” This form, this body, must be loved and respected, not put on the rack.

Here we begin to see how the question of the universality of the Church affects apparently unrelated questions, such as communion and divorce and remarriage. Ratzinger cited 1 Corinthians, where Paul describes the unity of the Church in terms of two sacraments—communion and matrimony. Just as the two become one flesh in marriage, so in the Eucharist the many become one body. “For we being many are one bread, and one body: for we are all partakers of that one bread.”

The connections Paul draws between marriage, the Eucharist, and Church unity should serve as a warning for whoever would tamper with one of the three. If the one body of the universal Church can be divided, the “one flesh” of a married couple can be as well. And communion—the sign of unity of belief and practice—can turn to disunion, with people who do not share the same beliefs joining together as though they did.

Kasper’s rejoinder came in an essay published in English byAmerica. It is the earliest and most succinct expression of what would become Pope Francis’s program. It begins with a key distinction: “I reached my position not from abstract reasoning but from pastoral experience.” Kasper then decries the “adamant refusal of Communion to all divorced and remarried persons and the highly restrictive rules for eucharistic hospitality.” Here we have it—all the controversies of the Francis era, more than a decade before his election.

(It should be noted that overwrought terms like adamant andhighly restrictive, for which Kasper has sometimes been criticized, were introduced by an enthusiastic translator and have no equivalent in the German text.)

Hovering in the background of this dispute, as of so many Catholic disputes, is the issue of liturgy. Ratzinger was already known as an advocate of the “reform of the reform”—a program that avoids liturgical disruption, while slowly bringing the liturgy back into continuity with its historic form.

Kasper, by contrast, uses the disruption that followed Vatican II to justify further changes in Catholic life: “Our people are well aware of the flexibility of laws and regulations; they have experienced a great deal of it over the past decades. They lived through changes that no one anticipated or even thought possible.” Evelyn Waugh described how Catholics at the time of the Council underwent “a superficial revolution in what then seemed permanent.” Kasper embraces that superficial revolution, hoping that it will justify another, profounder one.

He laments that Ratzinger does not see things his way: “Regrettably, Cardinal Ratzinger has approached the problem of the relationship between the universal church and local churches from a purely abstract and theoretical point of view, without taking into account concrete pastoral situations and experiences.” Ratzinger has failed to consult what Kasper calls the “data” of experience: “To history, therefore, we must turn for sound theology,” where we will find many examples of a commendable “diversity.”

Though Kasper’s language is strewn with clichés (“data,” “diversity,” “experience”), it has genuine rhetorical appeal. We want to believe that there can be peace, peace, though there is no peace between Church and world. Just as we can be moved by visions of unity, we can be beguiled by promises of comfort. The contrast between the two men is thus rhetorical as well as doctrinal: Ratzinger inspires; Kasper relieves.

America’s editors invited Ratzinger to respond, and he reluctantly agreed. His reply notes that baptism is a truly trinitarian event; we are baptized not merely in but into the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. We are not made members of one of various local Christian associations, but are united with God. For this reason, “Anyone baptized in the church in Berlin is always at home in the church in Rome or in New York or in Kinshasa or in Bangalore or wherever, as if he or she had been baptized there. He or she does not need to file a change-of-address form; it is one and the same church.”

Kasper closed the debate in 2001 with a letter to the editor, in which he argued that it “cannot be wholly wrongheaded … to ask about concrete actions, not in political, but in pastoral life.” There the controversy seemed to end.

Ratzinger became pope and Kasper’s proposal was forgotten.

Twelve years later, a newly elected Pope Francis gave Kasper’s proposal new life. In his first Angelus address, Francis singled out Kasper for praise, reintroducing him to the universal Church as “a good theologian, a talented theologian” whose latest book had done the new pope “so much good.” We now know that Francis had been reading Kasper closely for many years. Though he is usually portrayed as spontaneous and non-ideological, Francis has steadily advanced the agenda that Kasper outlined over a decade ago.

In the face of this challenge, Benedict has kept an almost perfect silence.

There is hardly any need to add to the words in which he resoundingly rejected the program of Kasper and Francis. And yet the awkwardness remains. No pope in living memory has so directly opposed his predecessor—who, in this instance, happens to live just up the hill. This is why supporters of Francis’s agenda become nervous whenever Benedict speaks, as he recently did in praise of Cardinal Sarah. Were the two men in genuine accord, partisans of Francis would not fear the learned, gentle German who walks the Vatican Gardens.

And so the two popes, active and emeritus, speaking and silent, remain at odds. In the end, it does not matter who comes last or speaks most; what matters is who thinks with the mind of a Church that has seen countless heresies come and go. When Benedict’s enraptured words are compared to the platitudes of his successor, it is hard not to notice a difference: One pope echoes the apostles, and the other parrots Walter Kasper. Because this difference in speech reflects a difference in belief, a prediction can be made.

Regardless of who dies first, Benedict will outlive Francis.

Matthew Schmitz is literary editor of First Things.

===================

Pilgrimages

If you would like to travel with Inside the Vatican to Russia, Ukraine and Rome in mid-July on our 4th annual Urbi et Orbi Foundation Pilgrimage, with meetings in Moscow and Kiev with leaders of the local Churches, please ask for more information by return email.

If you would like to make a very special journey with us to England in the footsteps of St. Thomas More at the end of June, please write to ask for more information.

Please consider subscribing to Inside the Vatican. If you do not subscribe, you will miss a great magazine.

Note: The Moynihan Letters go to more than 21,000 people around the world. If you would like to subscribe, simply emailme an email address, and I will add you to the list. Also, if you would like to subscribe to our print magazine, Inside the Vatican, please do so! It would support the old technology of print and paper, as well as these Moynihan Letters. Click here.

What is the glory of God?

“The glory of God is man alive; but the life of man is the vision of God.” —St. Irenaeus of Lyons, in the territory of France, in his great work Against All Heresies, written c. 180 A.D.

Facebook Comments