January 18, 2013, Friday — In the face of persecution

Yesterday, on the Feast of St. Anthony of Egypt, we announced the launch of a new Foundation, called the Urbi et Orbi Foundation, to seek greater unity among Christians, and, in particular, to forge a “strategic alliance” between Roman Catholics and the Orthodox, in order to face together the great challenges to the faith in our time. During the day today, we received nearly $20,000 in support of this effort, bringing our total in the past two weeks to about $40,000. Our goal is $250,000. We need that initial amount so that we can act effectively in a field where governments, foundations, and wealthy private individuals have resources in the billions. We will be giving grants of 90% of this money to common projects which seek to build bridges of trust and friendship between Catholics and Orthodox. We are seeking 100 founding members to join us at $2,500 per member. We now have 16 such founding members.

In Defense of the Faith: Toward and Alliance of Eastern and Western Christians

Benedict on Christian Unity from his First Homily as Pope

“With full awareness, therefore, at the beginning of his ministry in the Church of Rome which Peter bathed in his blood, Peter’s current Successor takes on as his primary task the duty to work tirelessly to rebuild the full and visible unity of all Christ’s followers. This is his ambition, his impelling duty.” —Benedict XVI, his first message as Pope, April 20, 2005

January 18, 2013

Dear friends,

Today was an exciting day. We received significant support for the new “Urbi et Orbi Foundation” we announced in a newsflash yesterday.

Still, we are very far from our goal.

Therefore, I am writing again to try to offer persuasive reasons why support for this effort is not only important, but crucial, for the future of the Christian faith in the modern world.

Some years ago, I asked a Roman cardinal what he thought of the Russians (he is a cardinal from eastern Europe who knew Pope John Paul II well). I had traveled several times to Russia, sometimes in connection with the story of the icon of Kazan, known popularly as “the protection of Russia,” which returned to Russia in 2004, just before John Paul’s death. So I visited with him, and asked him whether he thought we Westerners could “trust” the Russians.

“What do you think of the Russians?” I asked him.

“They suffered a lot,” he said to me. “They have good hearts.”

“What about us Americans?” I asked.

“Your hearts are not so good,” he said. “Your humanity has suffered from your affluence.”

I was profoundly shocked — as you may be as I relate this conversation.

I disagreed with the cardinal.

But I remembered his words, and meditated on them.

I continued to travel to Russia, visiting churches and monasteries, but also hospitals and orphanages, talking to bishops, priests and nuns, but also to government officials, students, taxi drivers. On one occasion, I spoke with a young Russian Orthodox layman who said this to me: “Here in Russia, the communist regime, from 1918 to 1991, for 73 years, attempted to suppress religious belief through direct attacks: restrictive laws, arrests, imprisonment; in a word, persecution. But somehow, the faith survived. It suffered greatly, but survived. In the West, the faith did not face such a direct persecution. It was legally permitted to exist. But a certain diminishment of the faith occurred precisely because your society was so open. Worldliness and pleasure were praised, spirituality and mysticism, often, mocked. In the end, I think, it may well turn out that the more effective persecution of the faith occurred in your country, not ours.”

Again, I was astonished — as you may be. His argument turned upside down much that I had long believed.

Over time, bit by bit, as I visited Catholic and Orthodox churches and shrines in the East, many filled with young people, and especially when I saw the Orthodox faithful in prayer, and heard them sing in their powerful way, and witnessed them bending down and placing their foreheads against the very pavement stones of their churches, I wondered: Where in the West have I seen such faith?

And the idea was born in me that we needed the East as much as the East needed us — perhaps more.

The longing for the transcendent is intrinsic to the human spirit. It is that “spark” which flies up toward the eternal which is “in the image and likeness of God.”

The desire for the infinite, for God, hidden though He may be — or glimpsed in the natural world around us, or sensed in the quiet of our hearts — is as innate to self-conscious minds, that is, to human minds, as the turning of leaves toward the sun is innate to living plants.

But this innate longing can be suppressed; can even, it seems, be completely eliminated. (This is what Dante meant when he wrote “so low had they fallen that they no longer considered themselves creatures worthy even of being damned.”)

And when this longing is eliminated it is, in my view, a colossal tragedy.

It is the loss of what is best in human beings. It is the loss of our highest identity, our distinctive, special nature. (I hesitate to say it is the loss of the soul, but it could also be that. And the combination of this loss in many souls constitutes the loss of the highest identity of a society, of the “better angels of our nature.” Of our society’s soul.)

This elimination of the longing for God can occur in two ways: (1) by direct persecution, until longing for God can become so painful and costly that a believer, even against his will, abandons the longing for what he knows, deep down, is his heart’s desire; or (2) by temptation, by the replacement of that pure and high longing with other longings, less high, less pure, beginning perhaps first with relatively harmless ones, like the longing to be healthy, and well-off, and well-thought of in society, but slowly, bit by bit, with a longing to satiate every desire, until a person desires, in the end, to forget about the transcendent altogether, to forsake it, as something that impedes the satisfaction of less sublime, more tangible desires. (Hence the Christian tradition of asceticism; not so much to reject the world, but to protect the delicate interior longing which would be diminished and finally extinguished by the world.)

In this second path to loss of faith, it is one’s own choice to leave the faith, and then to offer excuses for one’s abandonment (“it was something I believed in as a child, but I have now put away childish things”; “it was something I thought would give me joy, but it ended up preventing so many joys, so many pleasures, that I had to reject it, for my own happiness”; “it was a conviction based on myths and fables, now I see everything so much more clearly, and want only to have a quiet life free of spiritual struggle”).

Christ said that he came to cast a fire on the earth; the Holy Spirit descended upon the Apostles as tongues of fire; Moses saw a burning bush that burned, and was not consumed.

This very fire is what worldliness cools, dampens, douses. In the end, the faith flickers out.

This brings us to some reflections on where we are today, and a preliminary diagnosis of our predicament.

In our increasingly “globalized” world, we have a public culture based too much on “spin” rather than truth, on surface appearance rather than deeper reality, on the superficial rather than the profound.

Thus we have a need for a profound cultural renewal, a deepening across the board, a greater wisdom (I would say “a wisdom from on high” except that there is no direction in the spiritual realm, so it would be just as true to speak of “a wisdom from within”). Without this renewal, we will not be able to deal effectively, justly, humanely, lovingly, with the great challenges facing us: socially, politically, economically, technologically, environmentally.

But such a renewal can only occur if those operating in the culture are animated (literally, “breathed into”) by a profound wisdom, a profound understanding of human nature, of human weakness and sin, of human strength and nobility.

The great religious traditions of the world offer elements of this wisdom, and one of the tragedies of our age is that all of the great spiritual traditions of mankind have tended to be marginalized and abandoned as “archaic baggage” in this “brave new (technological) world” we find ourselves in.

All of mankind’s great religious traditions contain “elements” of the truth about human nature (as Vatican II notes), and the widespread abandonment of those “elements” has left humanity in many places “deracinated,” disconnected from ancient roots, and so subject to superficial winds of doctrine which circle the globe in this age of satellite news and the internet.

The ancient traditions, Christians believe, pointed toward and, as it were, “desired” the coming of Mary, of Jesus, and so also of all that unfolded, including the salvation accomplished in the death and resurrection of Christ. And a “Cristo-centric” view of cosmology holds that in that history, in those real events, something “cosmic” occurred which broke through the veil of frustration within which humanity stumbled gropingly, bereft of ultimate meaning and ultimate hope.

In the events of Christ’s life, death and resurrection, in the faith in the significance of these events, Christians find the culmination of human hopes, of “man’s search for meaning.”

There is no motive here for any sort of triumphalism. No motive for any sort of cultural imperialism. There is only a motive to be renewed not only in one’s longing for the divine — which is to be renewed in one’s innate humanness — but in the conviction that this longing responds to a reality, to the reality, to the central reality of the universe.

And it is not an accident that all of this came forth, in historical terms, starting with Abraham and then flourishing with Moses and the Exodus, then continuing with the prophets up through John the Baptist (who called on the people to repent and be renewed), that all this came forth from the people of Israel.

The spread of this “good news,” this “news” that hope had entered into the world, become incarnate in the world, to definitively overcome the frustration of the “saeculum,” the seculaer, by giving the secular an eternal horizon, was rapid, but also opposed, and harshly.

It was opposed by the imperial power of Rome, and by many Greek philosophers, and often by a part of Israel, as well as by many of the various pagan priesthoods.

But the coming, on Epiphany, of the Magi, the three Wise Men, from the East, to do Him homage, was an early sign of a universal destiny for this teaching, this faith, this news, which was not intended to shatter and destroy the spiritual traditions and longings of mankind, but to complement and complete them.

In the life of St. Anthony of Egypt, whose feast day we celebrated yesterday — the day we announced the launch of our new Foundation — we see all the elements of the conflict that this new faith provoked.

But the battle was less between cultural institutions than it was one within individual human souls. And so it will be today, and tomorrow.

Terry Matz, on the Catholic.org website, has this to say about St. Anthony:

“Two Greek philosophers ventured out into the Egyptian desert to the mountain where Anthony lived. When they got there, Anthony asked them why they had come to talk to such a foolish man? He had reason to say that — they saw before them a man who wore a skin, who refused to bathe, who lived on bread and water. They were Greek, the world’s most admired civilization, and Anthony was Egyptian, a member of a conquered nation. They were philosophers, educated in languages and rhetoric. Anthony had not even attended school as a boy and he needed an interpreter to speak to them. In their eyes, he would have seemed very foolish.

“But the Greek philosophers had heard the stories of Anthony. They had heard how disciples came from all over to learn from him, how his intercession had brought about miraculous healings, how his words comforted the suffering. They assured him that they had come to him because he was a wise man.

“Anthony guessed what they wanted. They lived by words and arguments. They wanted to hear his words and his arguments on the truth of Christianity and the value of ascetism. But he refused to play their game. He told them, ‘If you think me wise, become what I am, for we ought to imitate the good. Had I gone to you, I should have imitated you, but, since you have come to me, become what I am, for I am a Christian.’

“Anthony’s whole life was not one of observing, but of becoming…

“Saint Athanasius, who knew Anthony and wrote his biography, said, ‘Anthony was not known for his writings nor for his worldly wisdom, nor for any art, but simply for his reverence toward God.’

“Prayer: Saint Anthony, you spoke of the importance of persevering in our faith and our practice. Help us to wake up each day with new zeal for the Christian life and a desire to take the next challenge instead of just sitting still. Amen.”

And at the heart of the Orthodox monastic tradition, and of Orthodox ascetic spirituality, is this type of reverence for God, which we in the West need if we are to heal our wounded society and world.

The Anniversary of the Edict of Milan

In the year 313, the Roman Emperor Constantine issued an Edict from Milan making the Christian faith legal in the Roman Empire. Prior to that year, it had been illegal, and fiercely persecuted, in large measure because it refused to recognize in worldy authorities an absolute divinity, which was reserved only to God. And this was an essential reason why, from 30 AD to 313 AD, for 283 years, Christianity was persecuted by the rulers of the empire.

This year, 2013, we celebrate the 1,700th year since that Edict of Constantine. And Constantine was born in Nis, in what is today Serbia.

And the celebration began yesterday — the day we launched our Foundation, the day of the Feast of St. Anthony.

By chance, I received an interesting letter today from my friend Peter Anderson, a Catholic lawyer from the state of Washington who was a close friend of the late Russian Orthodox Patriarch Alexi and who has been one of my “mentors” on these matters in recent years. Anderson writes:

“The celebration of the 1700th anniversary of the Edict of Milan formally began last night with a major event at the National Theater in Nis (in Serbia).

“The principal speakers were Serbian Patriarch Irinej and Serbian President Tomislav Nikolic… The event was hosted by the newly-appointed Russian ambassador to Serbia, Alexander Chepurin, and the famous Sretensky Monastery Choir from Moscow sang at the event…

“The celebration of the Edict will culminate in Nis (Serbia) on October 6, 2013, in a liturgy celebrated by the patriarchs and primates of the various Local Orthodox Churches.

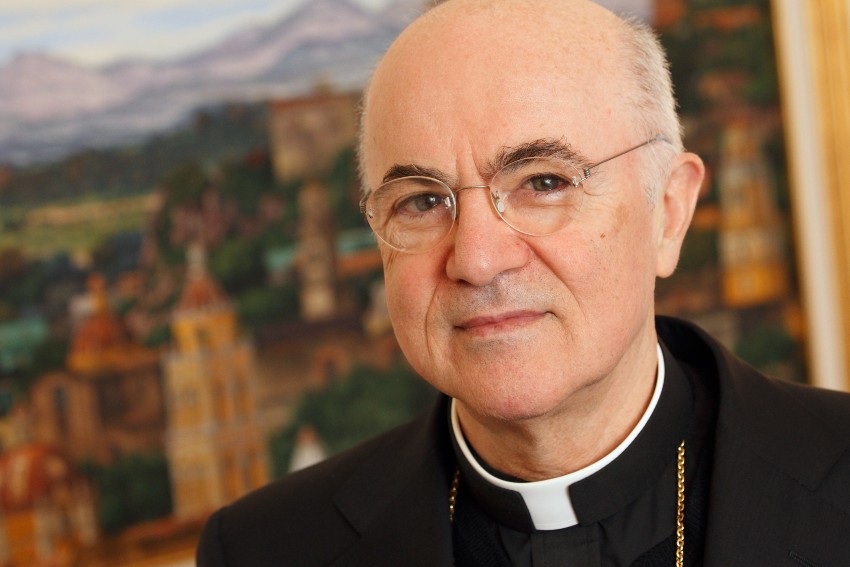

“It appears that representatives of other Christian churches will be invited to attend. Although Pope Benedict will presumably not be attending this celebration, the Catholic Church will have significant participation in the various celebrations. For example, the attached photo (from www.spc.rs) shows Archbishop Stanislav Hocevar, Catholic archbishop of Belgrade (on the left) and Archbishop Orlando Antonini, apostolic nuncio to Serbia (on the right) addressing the audience at last night’s event.

(Photo: Archbishop Stanislav Hocevar, Catholic archbishop of Belgrade, left, and Archbishop Orlando Antonini, apostolic nuncio to Serbia, right, addressing the audience at last night’s event to launch the 17ooth anniversary of Constantine’s Edict of Milan)

“Last Christmas, Archbishop Hocevar discussed the Catholic events in Serbia relating to the Edict. An interesting English-language article describes these events. https://www.b92.net/eng/news/society-article.php?yyyy=2012&mm=12&dd=21&nav_id=83775

“Significantly, Catholics will participate in the Orthodox events, and Orthodox will participate in the Catholic events. In September, Cardinal Angelo Scola of Milan will lead a pilgrimage at Nis.”

Here are excerpts from the pre-Christmas article Anderson cites, with emphasis added:

Catholic archbishop in Christmas message

BELGRADE — Roman Catholic Archbishop of Belgrade Stanislav Hočevar wished on Friday a merry Christmas to all those who celebrate it on December 25.

He also extended his good wishes to those who follow the Julian calendar…

“May all be blessed by rebirth and start 2013 reborn through the Holy Spirit and spend the year as new people, witnesses of a better and different world,” the archbishop stated.

Hočevar satisfied with joint jubilee plans

Stanislav Hočevar also said on Friday that he was satisfied that the new Serbian government and presidency initiated the joint marking of 1700th anniversary of the Edict of Milan in 2013.

“I am glad that on my initiative, Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić and Patriarch Irinej have included in that group the Roman Catholic Church, which has been the most vocal about that all these years,” Hočevar said after reading his Christmas message in the Archbishop of Belgrade.

He announced that panel discussions will be held as part of the celebrations on May 6 and 22, and a symposium on freedom from April 18-20.

The church dedicated to the ascension of the Holy Cross, which is being restored by great artists, will be consecrated in Nis on September 14, he noted.

Hočevar also announced that a pilgrimage will start from that church on September 20-21 under the leadership of Archbishop of Milan Cardinal Angelo Scola, as well as that the jubilee year will end in Belgrade with the celebration of the Feast of Christ the King.

“There will also be some other events related to the process of dialogue. After all reflections, we would like to end the next year by giving special consideration to the interpretation of history in these areas,” Hočevar said.

It has been agreed that representatives of the Roman Catholic Church will take part in the events organized by the Serbian Orthodox Church and vice versa, he added.

“It would be logical that the dialogue be fully realized at a meeting of all religious leaders, but that remains a possibility for our state in the future,” Hočevar said.

The Edict of Milan is a document issued by Constantine the Great in 313, which proclaimed religious tolerance and put a stop to the persecution of Christians.

The central ceremony will be held in Niš on October 6, 2013. This southern Serbian town was the birthplace of Rome’s first Christian emperor.

Working to End the Persecution of Christians

So this year, 1,700 years after the end of the great Roman imperial persecutions of Christianity, Catholics and Orthodox will celbrate the anniversary together in Serbia. And, who knows, perhaps on the central day of the year-long celebration, Orthodox and Catholic leaders could gather in Nis to give a great, dramatic sign of Christian unity…

This would be fitting in many ways, for the faith today is again being persecuted, after so many centuries of being legal and free.

In the 20th century, millions of Christians were executed for their faith under totaltitarian regimes which brooked no opposition from man or God, in countries ranging from Mexico to Cambodia to Germany to Russia.

And in our own 21st century, Christians in places like Nigeria face persecution and death in attacks by militant Muslims, while throughout the Middle East, there is a continuing exodus of Christians who face grave threats.

Even in western nations, new legislation threatens the religious freedom of Christians.

In this context, our new Foundation, the “Urbi et Orbi Foundation,” a group of lay Catholics which today added members from Argentina, Tanzania, Great Britain and Canada as well as many from the United States, alongside our partner, the St. Gregory the Theologian Foundation, a Russian Orthodox Foundation based in Moscow, will work to support persecuted Christians worldwide, and the human right of religious freedom.

In this effort, the alliance we hope to build between Roman Catholics and the Orthodox with whom we share so much — and especially with the Russian Orthodox, the largest of the Orthodox Churches — could be of great significance and effectiveness.

Please, consider whether this effort might not be something that you might wish to support.

All contributions are tax-deductible under US law; we will send a receipt from our 501(c)3 non-profit to be used for your tax filing purposes. I would be grateful if you would join with me in this initiative.

May God bless and protect you and your loved ones, and may you have a happy and holy New Year,

In Christ,

Dr. Robert Moynihan

Editor, Inside the Vatican magazine

Urbi et Orbi Foundation • 326 North Royal Ave • Front Royal, Virginia • 22630 • USA • Phone: 1-202-905-0433 • Toll-free line: 1-800-789-9494

P.S. To become a member of this new Foundation, it is sufficient to send a return email saying, “Yes, I would like to become a member,” and you will be enrolled as a member. To become a Founding Member, we are asking for donations of $2,500. (We are seeking 100 Founding Members; we already have 16.)

Facebook Comments