July 10, 2017, Monday

Hilarion and Butovo

“Every day they brought in and shot 200, 300, 400 people. There were 15-16-year-old children. Why were they shot?” —Russian Orthodox Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, on the executions in Butovo, a place on the sourthern edge of Moscow where more than 20,000 people were executed from the late summer of 1937 until the autumn of 1938 under the regime of Joseph Stalin (link). We met with Hilarion here in Moscow this morning

Today in Moscow it was cool, and in the morning there were some sprinkles of rain.

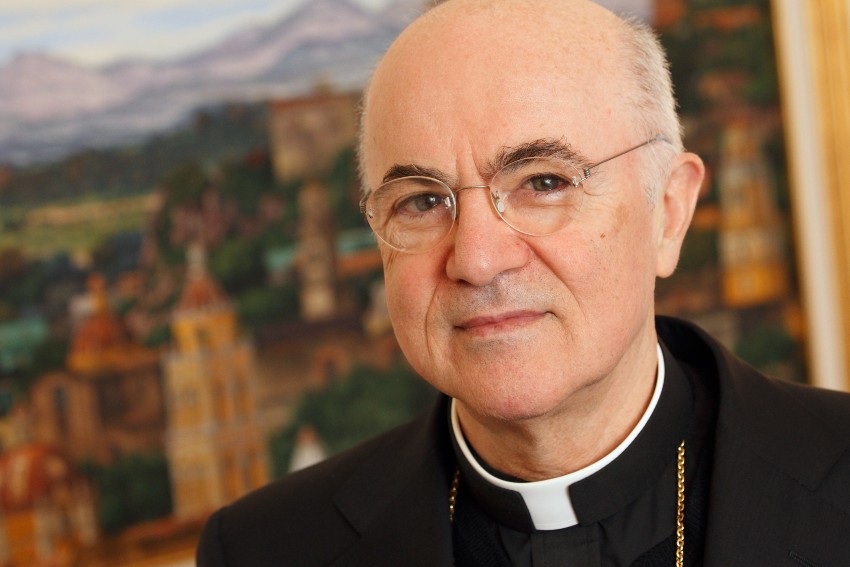

We were received this morning for about 30 minutes by Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, the head of the External Relations Department of the Moscow Patriarchate, in the Danilovsky monastery.

Our discussions focused on ways our Urbi et Orbi Foundation, an initiative of Catholic lay men and women I founded in 2012, might continue to collaborate on common projects with the Orthodox in order to “build bridges” of mutual understanding to improve relations between our long-divided Churches, and also between our countries, in a time when the United States and Russia seem to be on the verge of a new “Cold War,” with potentially grave consequences for regional and world peace.

Hilarion told us he is grateful for our collaboration thus far, and that he hopes it will continue. Our collaboration on small common projects like exchanges of scholars and seminarians between Rome and Moscow has borne quite positive fruits, he said. (Note: If you would like to support us in this work, please go to this link on our website, or write to me via return email; I will try to respond personally to all emails.)

Hilarion noted that, in this context — since many members of our Foundation are Americans — the recent long conversation, for about two and a half hours, between American President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin seemed a significant event. That meeting occurred on Friday, July 7, in Hamburg, Germany. (Here is a link to an article about the meeting.)

Hilarion asked us what out program was for our days in Moscow, and we told him that we intended to go tomorrow to Butovo, a place on the outskirts of Moscow where many thousands of people in the 1930s were executed under the regime of Joseph Stalin.

The place has now become a shrine to the Orthodox Church martyrs who died there, though many others, including Jews and non-believers, were also killed at Butovo.

“Good,” Hilarion said. “You should go.”

Then he told the story of an Orthodox Metropolitan from St. Petersburg who was arrested in the 1930s, though he was an old man in his 80s, and soon to die anyway of natural causes.

The old man was so weak that he was brought to Butovo on a stretcher, Hilarion said.

And then, when the old man reached Butovo, he was executed there, he said.

The Execution of the Innocent

This story moved all of us deeply.

The inhumanity of man to man can be astonishing; all people of good will can recoil at such pitilessness.

In a sense, this is the continuing theme of our present pilgrimage:

— that we all share a common humanity, which is, scripture tells us, in “the image and likeness of God”

— that this common humanity, our common frailty and mortality, our common struggle not to mar or surrender or lose that interior icon of the eternal divinity within us which is our most precious possession, which we once called the soul, which we might call our deepest and truest self, is a compelling reason for our mutual compassion, for our kindness to one another, as we all proceed on our common pilgrimage to our common end and judgment.

Our group includes Daniel Schmidt, retired vice president of the Bradley Foundation of Milwaukee, Wisconsin; William Forti, a retired executive with Gerneral Dynamics Corporation from Claremont, California; Curtis Kauffman, a retired journalist, also from Claremont; distinguished Catholic laywoman Kathleen Hessert Gunderman, founder and CEO of Sports Media Challenge, who has helped to shape the social media strategy and public image of such athletes as basketball champion Shaquille O’Neal, football champion Peyton Manning, and baseball champion Derek Jeter, from Charlotte, North Carolina; and Ivanna Richardson, who was born in Ukraine during the Second World War, but who has spent nearly all of her life in the United States, and who felt some hesitation in joining us in Russia for her first visit here ever, from Front Royal, Virginia.

Here is a New York Times article from 10 years ago, in 2007, by accomplished journalist Sophia Kishkovsky, whose work I greatly admire, about Butovo (link).

BUTOVO JOURNAL

Former Killing Ground Becomes Shrine to Stalin’s Victims

In Butovo, just outside Moscow, more than 20,000 people were shot to death and buried during the Stalinist terror of the 1930s.

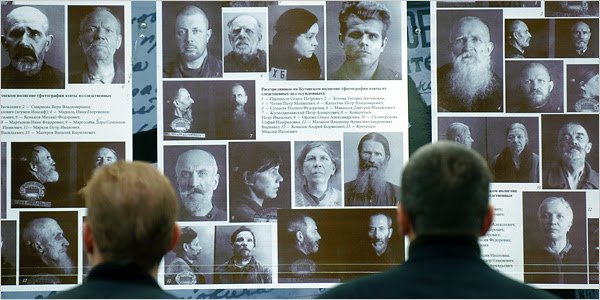

(In May 2007, visitors to the shrine there looked at secret police photos of victims, including many Russian Orthodox priests, who were executed as enemies of the people.)

By SOPHIA KISHKOVSKY

JUNE 8, 2007

BUTOVO, Russia — Barbed wire still lines the perimeter of the secret police compound here on the southern edge of Moscow where more, perhaps far more, than 20,000 people were shot and buried from August 1937 through October 1938, at the height of Stalin’s purges.

Now, gradually, Butovsky poligon — literally, the Butovo shooting range — is becoming a shrine to all of the victims of Stalin’s murderous campaigns.

Grass-covered mounds holding the victims’ bones crisscross the pastoral field, which is now dotted with flowers and birch trees.

Searing portraits from victims’ case files found in the archives of the secret police are displayed, along with a grim month-by-month chart of executions, in front of a small wooden church in the field.

“This place is our Russian Golgotha,” said Andrei Kuznetsov, 34, a social worker, making the sign of the cross recently in front of a newly built white stone church near the site, the Church of the Resurrection and the Holy New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia. “There is Golgotha in the Holy Land, where our Lord Jesus Christ suffered for our sins. All of Russia was Golgotha in the 20th century.”

The killing ground is a symbol of a much larger, bloodier conflict in Russian society, that between the Bolsheviks and the Russian Orthodox Church. One thousand of those killed here are known to have died for their Orthodox faith. More than 320 have been canonized as “new martyrs” of the church — bishops, monks, nuns and lay people who were victims of Soviet rule.

The new church was consecrated on May 19, 2007, as part of the celebration of the reunion of the Russian Orthodox Church and the Russian Church Abroad, an émigré group that broke away in the 1920s.

The walls of the church are filled with icons of the new martyrs, including one depicting their executioners shooting them.

Glass cases in the lower church are filled with their personal items, like an executed priest’s prayer book and his violin.

Visitors to the former killing ground, originally a military firing range, looked at the long row of monuments inscribed with names of the dead.

The names of the victims are engraved on plaques lining one of the fences around the field. The fence overlooks dachas that were built in a parklike setting for officials of the K.G.B., the secret police agency was a successor of the Stalin-era N.K.V.D. and endured until the collapse of the Soviet Union.

“They say the strawberries grew especially large at these dachas,” said Galina Pryakina, 70, nodding at the mounds of bones as she traced her finger across the plaques and found the name of a monk, now a saint, killed on the same day as her father, June 4, 1938.

She visited the site this year on the fourth Saturday after Easter, a day that Patriarch Aleksy II of the Russian Orthodox Church has chosen in recent years to commemorate Butovo’s martyrs. “I spent 66 years looking for him,” Ms. Pryakina said of her father. She was an infant when he was arrested, supposedly as a Romanian spy, and she and her mother were sent into exile.

Three years ago, she journeyed to Moscow from her home in southern Kazakhstan to find her father’s burial place. She headed for a cemetery in the city’s north, but a woman at a bus stop — Ms. Pryakina is convinced that it was a vision of the Virgin Mary — directed her to Butovo. Within minutes, her father’s name was tracked in a database here.

The Rev. Kirill Kaleda, rector of the Church of the Resurrection and the Holy New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia, has a tragically intimate connection to the parish.

His grandfather Vladimir Ambartsumov, who was a priest, is one of the new martyrs. He was arrested in 1937 and sentenced to “10 years without the right of correspondence,” the official euphemism for a death sentence. The Kaleda family spent decades searching for him.

“I remember very well how when we were little, after our morning and evening prayers, we would add a prayer asking to find how our Grandpa Volodya died,” Father Kaleda said. “It seemed that hope of learning the circumstances of Grandfather’s death had almost vanished. We had thought he died somewhere in the camps.”

Mikhail Mindlin, a concentration camp survivor who devoted his retirement in the 1980s and 1990s to systematically studying Soviet repression, fought to have the existence of the Butovo killing ground recognized by the state. Eventually, thanks to sympathetic K.G.B. officials, files with the names of those executed on the orders of Stalin’s henchman Nikolai I. Yezhov were found in secret police files.

The scope of the killings is staggering.

Butovo’s victims ranged from peasants and factory workers to czarist generals, Russian Orthodox hierarchs, German Communists, Latvian writers, invalids and even Moscow’s Chinese launderers, dozens of whom were executed as enemies of the people.

Ultimately many Soviet officials, including Yezhov and other N.K.V.D. officials who carried out the purges, were gunned down at Butovo and elsewhere as the revolution consumed its creators.

Some objections have been raised to the Russian Orthodox focus of the memorial, given the wide variety of victims buried here. But Arseny Roginsky, the chairman of Memorial, an organization that works to catalog Soviet crimes and help victims of repression, said the church had stepped into a void left by the state.

“It’s a bit strange that this is a purely Orthodox place, but nothing tragic,” he said. “I don’t really like this. I think this should be a multicultural place.

“But it’s better that there be something than nothing. If the state is not ready to understand the meaning of terror in its history, the role and place of terror in its history, it’s not so terrible that the Orthodox Church took it upon itself.”

=================

Tomorrow, Butovo…

So what is my point?

My point is that the Russians suffered enormously under Communism. And that Butovo is a place that stands symbolically for all of this suffering.

My point is that this suffering is little known, little remembered, in the West. And that it should be better known, better remembered.

My point is that, if we knew more about the suffering the Russian people passed through, we might understand in a deeper way the Russians’ own understanding of their history.

My point is that if we all were to have more knowledge and understanding of what others have passed through, more knowledge of what fathers were lost, what sons were lost, what brothers and sisters and friends and grandparents and acquaintances were lost, then we might begin to have the first elements of that compassion which could become a basis for the building of a just and durable international peace.

Tomorrow, then, we go to Butovo, in the hope that, even if we are tired, even if we are foreigners, even if we have not ourselves been directly affected by Butovo, even if we cannot fully understand what we will see, nevertheless we wish to stand there, in that place, to be present in Butovo, where suffering was profound 80 years ago.

We do this to be witnesses to long-ago men and women who were executed… to bear testimony that they have not been completely forgotten.

May this serve in some small way to prevent such events from ever occurring again.

To Butovo, then — a symbol of all those places where suffering has been borne by innocent men and women, and by those not executed who loved those innocent men and women, and lost them…

Facebook Comments