The cover of Monsignor Annibale Bugnini‘s classic work, The Reform of the Liturgy, 1948-1975 (Liturgical Press, Collegeville, Minnesota, 1990). Bugnini, who came from Umbria in the center of Italy, lived from 1912 to 1982 (link). Here is a link to a brief biography (link). Bugnini was for almost 30 years, from 1948 to 1975, the key Vatican figure in organizing the reform of the liturgy, which became the “new Mass.” (If you wish to refresh your memory about him, read the brief biography at the link just given.)

By reading Bugnini’s book, a Catholic may come to understand better how the Church decided to change from the old Latin Mass to the new Mass, a Mass essentially planned and composed under Bugnini’s direction.

The book was owned by my father, Prof. William Moynihan. He died at the age of 93 on March 28, 2020. He left me this book, which he had read and re-read. For he too, like so many of us, lived in a certain perplexity after the “reform of the liturgy” prepared in the 1960s and promulgated by Paul VI in 1970. He told me before he died that he hoped that his notes, which you can still see at the top of the book, and in the margins (see photo below), might help me to work my way through the book, which is 974 pages long.

So this book is my companion as a new stage in the battle over the Church’s liturgy commences.

This new stage commenced on Friday, July 16, 2021, three days ago, when Pope Francis decided to crack down on the spread of the old Latin Mass, which is attracting more and more young people, especially in the United States.

In so doing, Francis is reversing one of the signature decisions of Pope Benedict XVI, a decision for which Benedict was mocked, indeed hated, by many progressives in the Church.

Francis said he had decided to reverse Benedict’s reform — which granted a place of respect to the old Mass — because it had become “a source of division in the Church” and a rallying point for “Catholics opposed to the Second Vatican Council.”

So in this and future letters, I hope to offer my own imperfect reflection on these recent events, in dialogue with Bugnini himself.

I will come at the matter, as it were, from the side, using Bugnini’s own words, summoning him back, as it were, at this late date, 40 years after his death, to tell us what he and his colleagues did, and why they did it, when they set aside the old Mass, and gave us a new Mass instead.

I spoke with Archbishop Viganò this afternoon on the telephone. The archbishop said he is reflecting on these recent events. He encouraged me to study Bugnini’s book and to write about it.

My father, a Franciscan seminarian at Callicoon, New York, from 1943 to 1947, prayed daily that he might be worthy to become “a priest of God,” that is, worthy to celebrate the Mass, and all the mysteries (sacraments) of the church. He opened each of his diary entries with the sign of the cross. He closed many of his entries with the words “Maria, ora pro nobis“ [“Mary, pray for us”]. And he always prayed for the good of the Church, and for unity in the Church. As I write about these matters, I remember him. —RM

“An opportunity offered by St. John Paul II and, with even greater magnanimity, by Benedict XVI, intended to recover the unity of an ecclesial body with diverse liturgical sensibilities, was exploited to widen the gaps, reinforce the divergences, and encourage disagreements that injure the Church, block her path, and expose her to the peril of division.” —Pope Francis, in a letter issued on July 16 explaining his decision to greatly restrict the celebration of the “old Mass,” seen as a cause of “divergences,” “disagreements” and “divisions.” The reason for issuing this document, therefore, is to support unity in the Church based on the acceptance of the liturgy promulgated following Vatican II

“In prayer and obedience, I am reflecting on the motu proprio issued by Pope Francis and discerning how best to implement the changes. As permitted by the motu proprio, I intend to allow Masses in the Extraordinary Form to continue in the Diocese of Arlington.” —Bishop Michael Burbidge (link) tweeted (link), saying he intends to permit the old Latin Mass to be celebrated in his diocese, just outside of Washington D.C., and reaching to the Shenandoah Valley and the edge of West Virginia

Letter #58, 2021, Monday, July 19: Reflections on Guardians of Tradition and on Christian worship (link)

Pope Francis on July 16 reversed the welcoming guidelines toward the “old Mass” issued by Benedict XVI in the July 7, 2007 motu proprio Summorum Pontificum. Francis imposed restrictions on celebrating the old Latin Mass throughout the world.

His new letter, Guardians of Tradition, grants full authority to each diocesan bishop to regulate the celebration of the “old Latin Mass” in his diocese — yet asks the bishop to seek a “green light” from Rome before allowing any new group drawn to the old liturgy to be formed.

As I wrote last Friday, the true underlying issue is… Vatican II. The Council which sought to bring the Church “into the modern world.”

***

But the issue is not just Vatican II, understood narrowly.

The true issue is the Christian faith itself, at the crossroads (today) between the old world of “Christendom” (from Constantine to the French Revolution) and the new world (since the French Revolution) of “secular humanism,” and the world about to come upon us, variously called the world of “transhumanism” or of a “new humanity” or of “Homo sapiens 2.0″ or of the “Great Reset.”

And so the issue is, which form of prayer — which Mass, old or new — may more effectively defend the faith, and so also humanity itself, from a world and an ideology which is “anti-Christic,” which does not draw close to Christ, the Logos, but wishes at all costs to set Christ to one side, to forget about Him — to leave us bereft of the Logos of God, the greatest treasure we have or could have.

And all of this played out in two inter-related keys, which we name “lex orandi” and “lex credendi.”

The “law of praying” and “the law of believing.”

The point is that the two are related.

How we pray, is how we will believe.

That is the meaning of it.

If we pray in a reverent way, if we pray with veneration, with a sense of the awesomeness of the One we pray to, then we believe the One we pray to is awesome, Most High, divine, a reality “than which nothing greater may be conceived.”

But if we pray in an irreverent way, without veneration, without a sense of the awesomeness of the One we pray to, then we do not believe the One we pray to is awesome, Most High, divine, a reality “than which nothing greater may be conceived.”

The type of prayer we have, the type of Mass we have, will determine our belief.

One leads to the other.

And so, if men and women are made strong, courageous, fearless, free, not frightened even by death, by drawing close to God and to His Holiness in the liturgy, and if some looking on would wish men and women to be weak, cowardly, fearful, enslaved, afraid of death and distanced from God and His Holiness, then…. then it becomes of interest to some to change the lex orandi (the way of praying) in order to change the lex credendi (the way of believing).

Seen in this light, the old Mass — if one regards it as a liturgy which is profoundly holy, and so sanctifying — might be seen by some as a sort of “bulwark” against the secularizing of the entire human society… a bulwark which certain interests might wish to remove, first slowly, then abruptly.

***

The issue is, then, is whether the faith, the way we believe, what we believe… that is, what we believe about Christ (making us Christians)… is taught in all its truth and splendor (in a liturgy), or whether it is put under a shadow, made secondary to other concerns (often political or economic or social, “worldly” concerns, “secular” concerns).

This is the distinction between a “Christocentric” faith, or person — a faith or person centered on Christ — and a “human-centric” or “power-centric” or “money-centric” or “pleasure-centric” or, finally “self-centric” faith, or worldview, or person.

And this raises the question: which form of the Mass, which rite of the Mass, is more “Christocentric”? The old Mass, which Pope Francis (with advisors close to him) is now trying to suppress? Or the new Mass, which seems to be “more understandable,” “accessible” to the average person, yet which also seems to be significantly more “horizontal,” less oriented toward the “transcendent,” than the older rite?

***

The essential Christian teaching is that salvation — freedom, blessedness, true life, even meaning itself (Logos = “meaning”)… a life with meaning — comes from being “Christo-centric,” and that every other “center,” no matter how seemingly attractive, is a snare and delusion that leads to misery, slavery, ultimate frustration… meaninglessness.

In so far as the Church carries Christ, mediates Christ, speaks about Christ, communicates Christ, remembers Christ, prays to Christ, walks with Him, gives Him to mankind, the Church is giving freedom, blessedness, true life, every good thing.

The Church from the beginning has tried to do this daily, in daily prayer, in daily charitable action, in daily sacrifice, in daily worship, that is, in daily liturgy.

And through the centuries, knowing that human weakness, human selfishness, human pride, human treachery (even among clerics), can betray the Lord, set Him off to one side, offer to humanity something other than the one thing necessary — which Mary, sister of Martha, found when she gazed upon His face and drank in His words — the Church has attempted to purify the liturgy, so that it is not about ourselves, but about Him… veneration, worship… of Him.

And the place par excellence where the Church draws close to Christ, listens to Him, sings to Him, communes with Him, is in the Mass.

At Mass, a commemoration of the Last Supper, and of the Agony in the Garden, and of the Crucifixion, and of the silence of Holy Saturday, and of the Resurrection on that first Easter Sunday morning, all pressed together in an hour or so of hymns and prayers and readings, many of which date back to the very first years of the Church — indeed, the central words do date back to Him… the words at the Last Supper which are the words of the consecration.

That is the whole point of the liturgy: to bring the real Christ, again, daily, into the very presence of men and women, here and now.

***

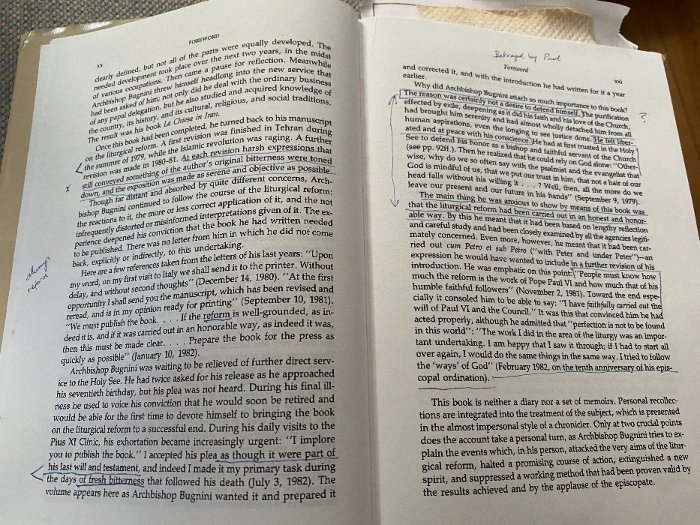

We are told in the Foreword to Bugnini’s book, written by his friend Fr. Gottardo Pasquale, I.M.C., that the book was “conceived, developed, and finally brought to birth in moments of great suffering.” (Here is a video of an interview with Fr. Pasquale in 2015; it is in Italian.)

This is startling.

Why would a book about the liturgy have involved “moments of great suffering”?

How could the choice of prayers, and hymns and gestures and use of bells and incense have matters of “great suffering”?

Clearly, there was some type of battle involved, some type of intellectual, or spiritual, struggle.

Clearly, organizing the “new Mass” was not simple, but complex, and filled with clashes and “suffering.”

In fact, Pasquale tells us that Bugnini, who had worked in the Vatican from 1948 until 1975, under Pius XII, John XXIII, and Paul VI, was suddenly removed from his post in 1975.

“In mid-July 1975… his service to the liturgy… came to an unexpected and almost dramatic end, without any plausible explanation being given to him,” Fr. Pasquale writes. “Months of utter silence followed during which no one but a very few faithful friends caught so much as a glimpse of him. These were days of bitter affliction for him…”

The, Paul VI assigned Bugnini to become… nuncio in Iran.

Iran had only a handful of Catholics. It is a “pearl” of a country, lovely — but not a country regarded as a prime posting for a Vatican diplomat!

While in Iran, Bugnini studied the country’s “history, and its cultural, religious and social traditions.” And he wrote a book, The Church in Iran.

During 1979, he revised his book on the liturgy (this was during the time when the American hostages were taken) and then during 1980-81.

Fr. Pasquale writes: “At each revision harsh expressions that still conveyed something of the author’s original bitterness were toned down, and the exposition was made as serene and objective as possible.”

What had caused Bugnini to feel so much bitterness?

The allegations made against him that he had carried out the liturgical reform in an improper way — and the way Pope Paul, seemingly, had given some credit to the allegations, removing him abruptly from his post and sending him to Iran.

Fr. Pasquale writes: “The main thing he was anxious to show by means of this book was that the liturgical reform had been carried out in an honest and honorable way… Toward the end especially it consoled him to be able to say: ‘I have faithfully carried out the will of Paul VI and the Council.'”

Fr. Pasquale ends the Foreword with these words: “The simple words he wanted on his tombstone — ‘He served the Church’ — characterized his life and explain his unwearying activity and unqualified obedience. They are his claim to glory.”

Still, if this is true, why was Monsignor Bugnini removed so abruptly, having to spend “months of utter silence”?

What is the real truth here?

(to be continued)

====================

Special note: I have been sending out so many emails that, for the first time, I reached the monthly limit established by the email service provider. To continue sending out emails (about 20,000 each time) I had to pay $500 this evening to increase my service limit, otherwise I would have been blocked until August 1. These emails are free, of course. If someone would like to cover a portion of the fees to send out the emails, it would be helpful. The fees amount to about $1,700 per year. (To make a donation, click here.)

The donations go to Urbi et Orbi Communications, which is an American non-profit that has published Inside the Vatican magazine since 1993. Urbi et Orbi also supports “building bridges” with the Orthodox world — including the Russian Orthodox — and our work in Lebanon, where we seek to help people who have faced tremendous hardship since the Beirut port explosion on August 4, 2020, a year ago. We are also this year launching a new Unitas project to try to use every means of communication to help the Church hold fast to “the faith once handed down” amid the difficulties we currently face. Please send a return email if you would like me to send you a complete report on this new Unitas project.—RM

First Reactions

Here are excerpts from an article by American Fr. John Zuhlsdorfabout the liturgy document, written three days ago, when the document first came out on July 16, Feast of Our Lady of Mr. Carmel — and also the anniversary of the day in 1054 when the “Great Schism” between East and West began. (Fr. Zuhlsdorf and I were students of Latin together under Fr. Reginald Foster at the Gregorian in the 1980s in Rome.)

First reactions to Traditionis custodes

[Note: The Latin words mean “Of Tradition the Guardians” or “Of Tradition the Custodians”] (link)

by Fr. John Zuhlsdorf

July 16, 2021

Today, 16 July, is the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. During the Amazonian Synod (“walking together”), it was at her church in Rome, near the Vatican, that the shrine to the demon Pachamama was set up.

Today, 16 July, is the anniversary of the Great Schism in 1054, when a Bull of Excommunication (not a Pachamama bowl) was lain on the altar of Hagia Sophia.

Today, 16 July, the Manhattan Project for the first time successfully detonated a nuclear weapon. Today is the anniversary of the first nuke in 1945.

In each of those cases, it took a long time to weigh the implications.

It also takes times to absorb and weigh the implications of legislative documents.

That leads me to my first reaction to the Motu Proprio, Traditionis custodes, which effectively insults the entire pontificate of Benedict XVI and the pastoral provisions of John Paul II and all the people they have affected.

Speaking of nukes, while this is quite awful, it is also good in that the line has been drawn. For all the cant about “unity” – which apparently is something to be forced not fostered – the divisions are now clearer.

Traditionis custodes. (…) This one just screams the maxim of Juvenal: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Without the whole sentence in Latin we can only guess at the meaning: “Overseers of betrayal…” is one option. “Protectors of surrender…”?

Because it takes time to weigh the implications – questions are flooding my mailbox and phone – I note the following at the end:

Everything that I have declared in this Apostolic Letter in the form of Motu Proprio, I order to be observed in all its parts, anything else to the contrary notwithstanding, even if worthy of particular mention, and I establish that it be promulgated by way of publication in L’Osservatore Romano, entering immediately in force….

“entering immediately in force”

There is no vacatio legis. There is no period of time between the promulgation and when it goes into effect. There is no period during which questions can be answered, changes can be arranged, plans can be made.

BAM.

Now people are writing to me to ask what they are supposed to do on Sunday. Priests are asking if they fulfill the obligation to say the Office with the Breviarium Romanum. The questions multiply even as I write. The first fruit of Traditionis is chaos.

(…)

There is a great deal more to say. However, I will leave you with this counsel.

Fathers… change nothing, do nothing differently for now. It is not rational to leap around without mapping the mine field we are entering. Keep Calm And Carry On.

Lay people… be temperate. Set your faces like flint. When you are on fire, it avails you nothing to run around flapping your arms. Drop and roll and be calm.

Lastly, a note of thanks is in order.

To those of you who have put your heart and goods and hopes into supporting and building the Traditional Latin Mass, thank you.

Do not for a moment despair or wonder if what you did was worth the effort, time, cost and suffering. It was worth it. It still is.

By your efforts you made it possible for many people to come close to an encounter with Mystery. That is of inestimable value and eternal merit.

By your efforts you supported many priests who deepened their appreciation of who they are, as priests, at the altar. The TLM brings forth this awareness in a way that the Novus Ordo does not. That’s why its enemies want to destroy it…

(…)

On this Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel – where Elijah slew the priests of Baal – entrust all of this to Mary, Queen of Priests.

[End Fr. Zuhlsdorf]

==============

And here is a very brief but very interesting report on one incident in the history of the “reform of the liturgy,” told to us by Fr. Louis Boyer, a convert from Lutheranism wrote out one of the prayers for the new Mass one evening in a trattoria in Trastevere in Rome…. (link)

Original Sins: Eucharistic Prayer II – composed in a few hours in a Roman Trattoria (link)

Perfect for “a banal on-the-spot product”

The unbelievable scene is not unknown, it has been mentioned elsewhere before, but now confirmed in the published recollections of one of the two men involved: during the mad rush to have the Novus Ordo Missae (the New Mass of Paul VI) ready as soon as possible, the Consilium, the 1963-1970 organization charged with the upheaval and destruction of the Roman Rite under the guise of “reform” and under the control mostly of Archbishop Annibale Bugnini, had reached a new level of ignominy in composing a new “canon.”

The draft was so bad and dangerous that the new Eucharistic Prayer had to be rewritten in a hurry and at the last minute during a late-night meeting by two men in a Roman restaurant.

For one and a half millennium, the Canon of the Roman Mass had been almost completely unchanged (which is why it was called a Canon, a rule, unchanged and unique).

Now, after the Council, and without a single mention in Sacrosanctum Concilium (the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy), the Consilium decided to offer new Anaphoras as if they were ice cream flavors.

The new “Eucharistic Prayers” were released in the fateful month of May 1968, while Western youth was on worldwide revolt (therefore, theoretically, for the 1965-1967 maimed version of the ancient Ordo Missae, but in truth preparing the way for the New Mass introduced in 1969).

Why the rush?

As with everything in the liturgical revolution, Bugnini and his minions knew they had to get everything done as fast as possible before they could be stopped by a dangerous wave of common sense.

They won.

And the Church got an aggressively-imposed new multiple-choice rite stuck in 1968.

The story of what would become the most popular of the new “Eucharistic Prayers” (Eucharistic Prayer II) is so insulting to the venerable Roman Rite that it beggars belief, and shows once again why the New Mass is the opposite of everything that is true and tested.

It is a shallow committee-work of out-of-touch “experts” so proud and revolutionary that they thought they were entitled to pass judgment on the immemorial heritage of almost 2,000 years of organic development and sincere devotion of saints, priests and faithful, something so bizarre that wiser minds have called it “a banal on-the-spot product.”

Cardinal Ratzinger was right to call the New Mass thus, as Sandro Magister makes clear below (translation from his Italian-language blog) when speaking of the memoirs of Fr. Louis Bouyer, one of the (later much disappointed) consultants of the Consilium. The memoirs were recently published in France by Éditions du Cerf:

The Fiery Memoirs of the Convert Paul VI Wished to Create Cardinal (link)

By Sandro Magister

September 16, 2014

Paul VI was seriously at the point of making him a cardinal, if he had not been held back by the ferocious reaction that the nomination would have certainly provoked among the French Bishops, led then by the Archbishop of Paris and President of the Episcopal Conference, Cardinal François Marty, a personality of “crass ignorance” and “devoid of the most elementary capacity of good sense.”

To have missed out on the cardinal’s hat and branded his arch-enemy in such a way was the great theologian and liturgist Louis Bouyer (1913-2003), as we learn in his blistering posthumous work Mémoires, published this past summer by Éditions du Cerf, ten years after his death.

Brought up as a Lutheran and later a pastor in Paris, Bouyer converted to Catholicism in 1939, attracted mainly by the liturgy, in which he distinguished himself before long as an expert authority with his masterpiece The Paschal Mystery, on the rites of Holy Week.

Called to be part of the preparatory commission for the Second Vatican Council, he understood immediately and instinctively its greatness as well as its poverty, and he got out of it fast.

He found the cheap ecumenism “from Alice in Wonderland” from that age unbearable.

Among the few conciliar theologians spared by him was the young Joseph Ratzinger, who gets only praises in the book. And vice-versa, among the few high churchmen who immediately appreciated the talent and merits of this extraordinary theologian and liturgist, the one who stands out most is Giovanni Batttista Montini, who was still Archbishop of Milan.

On becoming Pope and taking the name of Paul VI, Montini wanted Bouyer on the commission for the liturgical reform, “theoretically” presided over by Giacomo Lercaro, “generous” but “incapable of resisting the manipulations of the wicked and mellifluous” Annibale Bugnini, Secretary and factotum of the same organism, “lacking as much in culture as in honesty.”

It was Bouyer who had to remedy in extremis a horrible formulation of the new Eucharistic Prayer II, from which Bugnini even wanted to delete the “Sanctus.”

And it was he who had to rewrite the text of the new Canon that is read in the Masses today, one evening, on the table of a trattoria in Trastevere, together with the Benedictine liturgist, Bernard Botte, with the tormenting thought that everything had to be consigned the following morning.

But the worst part is when Bouyer recalls the peremptory “the Pope wants it” that Bugnini used to shut up the members of the commission every time they opposed him; for example, in the dismantling of the liturgy for the dead and in purging the “imprecatory” verses from the psalms in the Divine Office.

Paul VI, discussing with Bouyer afterwards about these reforms “that the Pope found himself approving, not being satisfied about them any more than I was,” asked him.

“Why did you all get mired in this reform?”

And Bouyer [replied], “Because Bugnini kept assuring us that you absolutely wanted it.”

To which Paul VI [responded]: “But how is this possible? He told me that you were all unanimous in approving it…”

Bouyer recalls in his Mémoires that Paul VI exiled the “despicable” Bugnini to Teheran as Nuncio, but by then the damage had already been done.

For the record, Bugnini’s personal secretary, Piero Marini, would then go on to become the director of pontifical ceremonies from 1983 to 2007, and even today there are voices circulating about him as the future Prefect for the Congregation of Divine Worship. …

[Source, in Italian (main excerpt). Translation: contributor Francesca Romana]

For more on the origins of the made-up new Eucharistic Prayers, see, among others, this 1996 article by Fr. Cassian Folsom, OSB, who would later become the founding prior of the Monastery of Saint Benedict in Nursia (Norcia), Italy.

[End Rorate Caeli piece, citing a 2014 Sandro Magister piece, which cites Fr. Louis Bouyer in a posthumous book published in 2013, 10 years after his death in 2003]

Facebook Comments