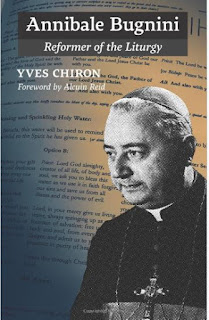

“It would be most inconvenient for the articles of our Constitution to be rejected by the Central Commission or by the Council itself. That is why we must tread carefully and discreetly. Carefully, so that proposals be made in an acceptable manner (modo acceptabile), or, in my opinion, formulated in such a way that much is said without seeming to say anything: let many things be said in embryo (in nuce) and in this way let the door remain open to legitimate and possible postconciliar deductions and applications; let nothing be said that suggests excessive novelty and might invalidate all the rest,…” —Monsignor Annibale Bugnini, the head of the Commission which prepared the new Mass, explaining his method of proceeding. The words are cited in a fairly recent biography of Bugnini by French Catholic scholar Yves Chiron; the book’s cover is shown above, with a photo of Bugnini (link). The book was published on November 26, 2018, almost 3 years ago

“A two thirds majority [of bishops in 1967, viewing a trial celebration of the new Mass] was needed to approve the new rite and only a third voted against it, a fact already known; what was largely unknown is that another third of bishops, uncomfortable with the new Mass and equally uncomfortable opposing the Pope, voted ‘present.'” —from the same biography

“One last insight provided by the author is a debasement of the long held rumor that Archbishop Bugnini was a subversive Mason, a member of the Lodge bent on destroying the Church from within. When Paul VI decided to abolish both the Consilium and Congregation for Sacred Rites, he elected to create a new commission to handle the regulation of his new liturgy. Bugnini was the obvious choice, but was, inevitably, not the choice. Why? The author sides with those who think Pope Paul was simply tired of Bugnini, his methods, and his antics.” —from the same biography

Letter #61, 2021, Wednesday, July 21: Review of a recent biography of Monsignor Bugnini

It seemed useful to fill in a bit more background information before studying Monsignor Annibale Bugnini‘s classic, lengthy work, The Reform of the Liturgy (link to purchase the book; note that the price of the book at this link is $902, not a price most readers could afford).

Here is a review. It serves to give an overview of the life of the man and his work. (Thanks to the author.)

(1) Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy (book review)

By “The Rad Trad,” an American who lives in New Hampshire (link)

February 6, 2019

The world knows Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg. Does it know Tim Berners-Lee? The world knows “Uncle Joe” Stalin. Does it know Ion Mihai Pacepa? Jobs gave us the iPhone and Zuckerberg some blue website, but Berners-Lee gave us the internet. Stalin took over Eastern Europe and committed genocide, but Pacepa inculcated materialism and jealously into the hearts of academics and undergraduates throughout the West. The real work of changing the world is so often obscured by those who later reap its laudatory recognition.

Similarly, Paul VI is given the credit for the final form of the Roman liturgy which emerged in the late 1960s. Responsibility for the Liturgia Horarum and Novus Ordo Missae do inevitably fall upon Giovanni Bautista Montini, who signed his regnal name under the decrees promulgating their uses, but the creation of these rites belongs to the less known and more obscure Annibale Bugnini.

We know the name Bugnini and we know the product of his work. What we do not know is the man and his life. We do not know how the man who changed how we pray actually prayed himself. We do not know how the man who influenced how we related to God himself related to God. We do now know how the man who wrote the liturgy himself understood the liturgy. Yves Chiron‘s Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy does not answer all of these questions, but it does open a substantial aperture into the life and decisions of a man whose traces remain in the trace of every western Christian.

The Author

Yves Chiron is a French essayist and historian who has written extensively on the history of the modern papacy, the saints, and the contemporary state of the Church. A traditionalist, but a staid one, a Francophonic correspondent likened him to a “more intellectual version of Michael Davies.” Not many of Chiron’s works have made it into English, but Annibale does reflect an objective approach to the sensitive subject matter, an interest in connecting the facts, and a respectable refrain from voicing an opinion until the end of the work.

The Book

Annibale Bugnini was born near Orvieto to a sharecropper and his wife. The fifth of seven children, Annibale came from a pious family that attended the great feasts of the Church and made an annual pilgrimage to Santa Maria de Scopulis during the Paschal octave. Half the children went into the religious life, Annibale himself into the Vincentians.

Chiron follows his subject through his religious studies in Siena and his initial interest in liturgy. He loved the major feasts with tremendous enthusiasm and would readily put on a cassock in the sacristy of any church if given the chance to introire ad altare Dei. Liturgy, Chiron suggests, was an enthusiasm for Bugnini. His real interest was in managing people, a skill which would inform his life’s work much more than his expertise. A student in Siena, he wrote his dissertation on the role of committees during the Council of Trent.

After ordination to the priesthood, Bugnini made two pivotal moves which would determine the direction of his ecclesiastical career. First, he accepted the directorship of a failing liturgical journal called Ephemerides Liturgicae, which had fallen to 96 subscribers.

Under Bugnini’s niche interest in “pastoral liturgy,” readership increased into the thousands.

The other major step was Bugnini’s first and only pastoral experience as a weekend chaplain in a poor Roman suburb [presumably] celebrating low Mass for the locals. Here, he nursed his “pastoral” angle on the liturgy by having a “reader” hold up large cardboard signs which commented on the Mass or translated the priest’s words into Italian and which prompted the congregation to reply in Italian. Something new was in the mix.

We then follow the aspiring liturgist to the Le Thieulin conference in 1946, a gathering of like minded promoters of the Liturgical Movement and all its aspirations. Here Bugnini met Dom Beauduin, Yves Congar OP, and the progressive Georges Chevrot. The mutual meeting effected the formation of the Centro di Azione Liturgica, which gave this particular brand of the Liturgical Movement its form and Carlo Braga his first job.

Bugnini played his modest part in the Pian reforms to Holy Week, in which he was a passive secretary more than an active participant. After the election of John XXIII [1958] and the calling for an ecumenical council, Bugnini was appointed secretary for the new commission charged with drafting the Conciliar agenda and documents regarding the liturgy. Here emerged what the author astutely denominates the “Bugnini method.”

Normally, a secretary functions as a minute-taker, an envoy for someone in greater authority, and a delegated staffer. Bugnini employed his talents for bureaucracy and used his unique position to create various factions within the preparatory commission, isolate them, and then dictate their agenda to them. He created thirteen subcommissions, each dedicated to a particular function such as vernacular, sacred music, concelebration, the Office, and more. No one subcommission could influence the work of another subcommission nor consult them. Everything had to be done through Father Bugnini.

In the preparatory commission, Bugnini set the agenda for each commission and by putting hitherto unconsidered matters on the table, he moved what political scientists call the “Overton window” such that some movement on these issues was inevitable. Wary of backlash, Bugnini instructed members of the subcommissions drafting sections of what would be called Sacrosanctum Concilium not to be too forward in their views on the vernacular, concelebration, or the extent to which they desired to reform the entire liturgy:

“It would be most inconvenient for the articles of our Constitution to be rejected by the Central Commission or by the Council itself. That is why we must tread carefully and discreetly. Carefully, so that proposals be made in an acceptable manner (modo acceptabile), or, in my opinion, formulated in such a way that much is said without seeming to say anything: let many things be said in embryo (in nuce) and in this way let the door remain open to legitimate and possible postconciliar deductions and applications; let nothing be said that suggests excessive novelty and might invalidate all the rest, even what is straightforward and harmless (ingenua et innocentia). We must proceed discreetly. Not everything is to be asked or demanded from the Council—but the essentials, the fundamental principles [are].”

In 1962, Bugnini was informed that Ferdinando Antonelli OFM would be named head of the Conciliar commission on the liturgy. Bugnini, in a risible fit of extraordinary self-entitlement one usually only sees in college sororities, wrote everyone he knew asking for the job, citing his “bitterness” and the harm done to his reputation. At the same time he was fired from his job teaching at the Lateran University. He appealed to Pope John, who either willed his dismissal or consented to it.

Bugnini’s double edged sword, Sacrosanctum Concilium, passed muster in Saint Peter’s Basilica during Vatican II; even Archbishop Lefebvrevoted for it (although bishops were hardly given the time to read the documents). Now Giovanni Battista Montini was Pope Paul VI and he restored Bugnini to his secretariat on the Conciliar commission.

What is most impressive, and new, in Chiron’s research is that he has uncovered Bugnini’s takeback of control of the reform project. The Consilium, under the nominal leadership of Cardinal Lercaro, was to be dissolved and the reforms to the Mass and Office would descend upon Cardinal Larraona and his Congregation for Sacred Rites. The Consilium managed to appoint itself reformer of the liturgy.

From here, we are familiar with the history. Our author does, however, supply us with new and useful tidbits, including the startling reaction of the 1967 Synod of Archbishops who viewed three experimental Novus Ordo Masses in the Sistine chapel. A two thirds majority was needed to approve the new rite and only a third voted against it, a fact already known; what was largely unknown is that another third of bishops, uncomfortable with the new Mass and equally uncomfortable opposing the Pope, voted “present.”

Pope Paul eventually saw a spoken rendition of the Novus Ordo himself and suggested numerous changes (returning the Kyrie, keeping the triple Agnus Dei, and retaining the Last Gospel). Apparently the new Mass was to have even less of the old Mass than it does now.

One last insight provided by the author is a debasement of the long held rumor that Archbishop Bugnini was a subversive Mason, a member of the Lodge bent on destroying the Church from within. When Paul VI decided to abolish both the Consilium and Congregation for Sacred Rites, he elected to create a new commission to handle the regulation of his new liturgy. Bugnini was the obvious choice, but was, inevitably, not the choice. Why? The author sides with those who think Pope Paul was simply tired of Bugnini, his methods, and his antics.

Montini intended to sent Bugnini on a Papal Embassy to Latin America, but Bugnini objected on the grounds of his ignorance of Spanish. Instead he was sent to Tehran. Those who believe him to be a Freemason have their roots in Cardinal (Silvio) Oddi, who stated to Tito Casini that he had seen evidence that Bugnini was an affirmed member of the Lodge.

Archbishop (Marcel) Lefebvre repeated this rumor in 1975 and began an accusation that lingers until our own day. Ironically, while in his second exile, Bugnini wrote to Paul VI suggesting that Lefebvre and the Seminary of Saint Pius X be given permission to use the old Mass under similar conditions to the “Agatha Christie Indult” in England; he was ignored and Rome’s relations with the French missionary deteriorated.

Conclusions

There is much more in Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy that cannot be covered in a simple review: his influence on papal ceremonies, his war against the collegiate churches of Rome in their effort to preserve Gregorian chant, and his very human reactions to the political situation in Iran.

Chiron has given his reader much food for thought without explicitly telling them what to think. The cover of this book is, fitting, a picture of Msgr. Bugnini against a page for the introductory rites of the Novus Ordo Missal. We can see any number of option greetings, aspersions with lustral water, or a penitential rite. The choice is left with the reader of the Missal.

Similarly, conclusions about Bugnini are left with the reader.

To the progressive, he will be a noble warrior who patiently dealt with the Baroque liturgical establishment in Rome until he found the moment to spring forward and initiate renewal.

To the traditionalist, Bugnini comes across as a double dealing, mealy mouthed ignoramus who spent decades destroying sacred things and replacing them with his own machinations.

The moderate and the conservative, however, are so confronted with facts that they have no where to hide, no where to talk about the misinterpretation of Vatican II or the silvering linings of the reform; either Bugnini was a scoundrel or the agent of reform.

Chiron only departs from his dispassionate facts and gives an opinion on the last page. The opinion is his own, but Joseph Ratzinger supplies the words:

“On the other hand, the liturgical reform enacted after Vatican II made ‘the liturgy appear to be no longer a living development but the product of erudite work and juridical authority; this has caused us enormous harm.'”

Two comments from readers are posted at the bottom of this review.

The first asks: “What did the vote ‘present’ mean? A form of abstention?”

The review author answers: “Yes, it means they were just as uncomfortable with the new Mass as they were with the idea of opposing the Pope directly.”

The second refers to the sentence in the book review: “One last insight provided by the author is a debasement of the long held rumor that Archbishop Bugnini was a subversive Mason.”

The review author answers: “My impression is not that Chiron debases it, but that he is unable to find sufficient information to either deny or confirm it: it [the judgment on this question] is ‘inconclusive.’ He seems more firm that it seems not to have been decisive in Paul VI’s decision to remove him. That said, it is interesting to read in the Foreword by Alcuin Reid in which he mentions a 1996 interview with (Austrian) Cardinal Alfons Stickler (1910-2007) in which he [Stickler] is asked if he believed that Bugnini was a Freemason and if this was the reason Paul VI dismissed him. “No,” the cardinal replied, “it was something far worse.”

[End, book review and reader’s comments]

Facebook Comments