Thursday, February 18, 2021

Traditional Feast of St. Bernadette Soubirous of Lourdes, France (born in Lourdes on January 7, 1844, died in Nevers, April 16, 1879, age 35) [Note: her Feast was originally on February 18, that is, today, the anniversary of the day Mary promised to make her happy, “not in this life, but in the next,” but her Feast has come to be observed in most places on April 16, the day of Bernadette’s death]. She is Patroness of bodily illness, of Lourdes, France, of shepherds and shepherdesses, against grinding poverty, and of those ridiculed for their faith. Today is also the Feast of Blessed Fra Angelico (1395-1455), Patron of All Artists

Bernadette Soubirous (January 7, 1844-April 16, 1879), also known as St. Bernadette of Lourdes, was the firstborn daughter of a miller from Lourdes, in the department of Hautes-Pyrénées in France, and is best known for receiving Marian apparitions, seeing over several months a “young lady” who asked for a chapel to be built at the nearby cave-grotto at Massabielle. These apparitions occurred between February 11 and July 16, 1858, when Bernadette was 14, and the woman who appeared to her identified herself as the “Immaculate Conception.”

After a canonical investigation, Bernadette’s reports were declared “worthy of belief” on February 18, 1862 (that is, 159 years ago today) and the Marian apparition became known as Our Lady of Lourdes. Since her death, her body has remained substantially incorrupt. The Marian shrine at Lourdes has become a major pilgrimage site, attracting more than five million pilgrims of all denominations each year.

On 8 December 1933, Pope Pius XI, declared Bernadette a saint of the Catholic Church. Her feast day, initially specified as February 18 — the day Mary promised to make her happy, “not in this life, but in the next” — is now observed in most places on the date of her death, April 16.

Bernadette was the eldest of nine children, several of whom lived only a brief time—(1) Bernadette, (2) Jean (born and died 1845), (3) Toinette (1846–1892), (4) Jean-Marie (1848–1851), (5) Jean-Marie (1851–1919), (6) Justin (1855–1865), (7) Pierre (1859–1931), (8) Jean (born and died 1864), and (9) a baby named Louise who died soon after her birth (1866).

She was born on January 7, 1844, and baptized at the local parish church, St. Pierre’s, on January 9, her parents’ wedding anniversary. Her godmother was Bernarde Casterot, her mother’s sister, a moderately wealthy widow who owned a tavern. Hard times had fallen on France and the family lived in extreme poverty. Bernadette was a sickly child and possibly due to this grew only to a height of 1.4 meters (4 feet 7inches). She contracted cholera as a toddler and suffered severe asthma for the rest of her life. Bernadette attended the day school conducted by the Sisters of Charity and Christian Instruction from Nevers. Contrary to a belief popularized by Hollywood films, Bernadette learned very little French, only studying French in school after age 13. At that time she could read and write very little due to her frequent illnesses. She spoke the language of Occitan, which was spoken by the local population of the Pyrenees region at that time and to a residual degree today (which is similar to Catalan spoken in eastern Spain).

Lourdes apparitions in 1858

By the time of the events at the grotto, the Soubirous family’s financial and social status had declined to the point where they lived in a one-room basement, formerly used as a jail, called le cachot, “the dungeon”, where they were housed for free by her mother’s cousin, André Sajoux.

On February 11, 1858, Bernadette, then 14, was out gathering firewood with her sister Toinette and a friend near the grotto of Massabielle (Tuta de Massavielha) when she experienced her first vision.

While the other girls crossed the little stream in front of the grotto and walked on, Bernadette stayed behind, looking for a place to cross where she wouldn’t get her stockings wet. She finally sat down to take her shoes off in order to cross the water and was lowering her stocking when she heard the sound of rushing wind, but nothing moved. A wild rose in a natural niche in the grotto, however, did move. From the niche, or rather the dark alcove behind it, “came a dazzling light, and a white figure.”

This was the first of 18 visions of what she referred to as aquero, Gascon Occitan for “that.” In later testimony, she called it “a small young lady” (uo petito damizelo). Her sister and her friend stated that they had seen nothing.

On February 14, after Sunday Mass, Bernadette, with her sister Jean-Marie and some other girls, returned to the grotto. She knelt down immediately, saying she saw the apparition again and falling into a trance. When one of the girls threw holy water at the niche and another threw a rock from above that shattered on the ground, the apparition disappeared.

On her next visit, February 18, Bernadette said that “the vision” asked her to return to the grotto every day for a fortnight.

This period of almost daily visions came to be known as la Quinzaine sacrée, the “holy fortnight.” Initially, Bernadette’s parents, especially her mother, were embarrassed and tried to forbid her to go. The supposed apparition did not identify herself until the 17th vision. Although the townspeople, who believed she was telling the truth, assumed she saw the Virgin Mary, Bernadette never claimed it to be Mary, consistently using the word aquero. She described the lady as wearing a white veil, a blue girdle and with a yellow rose on each foot — compatible, observers have noted, with a description of “any statue of the Virgin in a village church.”

Bernadette’s story caused a sensation with the townspeople, who were divided in their opinions on whether or not she was telling the truth. Some believed her to have a mental illness and demanded she be put in an asylum.

The words Bernadette heard spoken in her visions were quite simple and focused on the universal need for “prayer and penance.”

On February 25, 1858, Bernadette explained that the vision had told her “to drink of the water of the spring, to wash in it and to eat the herb that grew there,” as an act of penance. To everyone’s surprise, the next day the grotto was no longer muddy but clear water flowed.

On March 2, at the 13th of the apparitions, Bernadette told her family that the lady said that “a chapel should be built and a procession formed.”

Her 16th vision, which Bernadette said went on for over an hour, was on March 25. According to her account, during that visitation, she again asked the woman for her name but the lady just smiled back. She repeated the question three more times and finally heard the lady say, in Gascon Occitan, “I am the Immaculate Conception” (Qué soï era immaculado councepcioũ, a phonetic transcription of Que soi era immaculada concepcion).

Results of Bernadette’s visions

After investigation, Church authorities confirmed the authenticity of the apparitions in 1862.

In the more than 150 years since Bernadette dug up the spring, 69 miraculous cures have been verified by the Lourdes Medical Bureau, which judged them “inexplicable” after “extremely rigorous scientific and medical examinations” failed to find any other ordinary explanation.

The Lourdes Commission that examined Bernadette after the visions ran an intensive analysis on the water and found that, while it had a high mineral content, it contained nothing out of the ordinary that would account for the cures attributed to it. Bernadette said that it was faith and prayer that cured the sick: “One must have faith and pray; the water will have no virtue without faith.”

The Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes is now one of the major Catholic pilgrimage sites in the world. One of the churches built at the site, the Basilica of St. Pius X, can accommodate 25,000 people and was dedicated by the future Pope John XXIII when he was the Papal Nuncio to France. Close to 5 million pilgrims from all over the world visit Lourdes (population about 15,000) every year to pray and to drink the miraculous water, believing they obtain from the Lord healing of body and spirit.

Later years

Disliking the attention she was attracting, Bernadette went to the hospice school run by the Sisters of Charity of Nevers where she had learned to read and write. Although she considered joining the Carmelites, her health precluded her entering any of the strict contemplative orders. On July 29, 1866, with 42 other candidates, she took the religious habit of a postulant and joined the Sisters of Charity at their motherhouse in Nevers. The Mother Superior at the time gave Bernadette the name Marie-Bernarde.

Patricia A. McEachern observes, “Bernadette was devoted to St. Bernard, her patron saint; she copied long texts related to him in notebooks and on bits of paper. The experience of becoming ‘Sister Marie-Bernarde‘ marked a turning point for Bernadette as she realized more than ever that the great grace she received from the Queen of Heaven brought with it great responsibilities.”

Bernadette spent the rest of her brief life at the motherhouse, working as an assistant in the infirmary and later as a sacristan, creating beautiful embroidery for altar cloths and vestments. Her contemporaries admired her humility and spirit of sacrifice. One day, asked about the apparitions, she replied: “The Virgin used me as a broom to remove the dust. When the work is done, the broom is put behind the door again.”

Unfortunately, her childhood case of cholera left Bernadette with severe, chronic asthma, and eventually she contracted tuberculosis of the lungs and bones. For several months prior to her death, she was unable to take an active part in convent life. She eventually died at the age of 35 on April 16, 1879 (the Wednesday after Easter), while praying the holy rosary. On her deathbed, as she suffered from severe pain and in keeping with the Virgin Mary’s admonition of “Penance, Penance, Penance,” Bernadette proclaimed that “all this is good for Heaven!”

Her final words were, “Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for me, a poor sinner, a poor sinner.”

Sainthood

Bernadette was declared blessed on June 14, 1921, by Pope Pius XI. She was canonized by Pius XI on December 8, 1933.

Blessed Fra Angelico

Fra Angelico was an Italian painter of the early Renaissance who combined the life of a devout friar with that of an accomplished painter. He was called Angelico (Italian for “angelic”) and Beato (Italian for “blessed”) because the paintings he did were of calm, religious subjects and because of his extraordinary personal piety.

Born Guido di Pietro; c. 1395 – February 18, 1455), Fra Angelico was described by Vasari in his Lives of the Artists as having “a rare and perfect talent.” He earned his reputation primarily for the series of frescoes he made for his own friary, San Marco, in Florence. From 1447 to 1449, he worked at the Vatican, designing the frescoes for the Niccoline Chapel for Pope Nicholas V.

He was known to contemporaries as Fra Giovanni da Fiesole (Brother John of Fiesole) and Fra Giovanni Angelico (Angelic Brother John). In modern Italian he is called Beato Angelico (Blessed Angelic One); his common English name, Fra Angelico, means “the Angelic friar.”

In 1982, Pope John Paul II proclaimed his beatification in recognition of the holiness of his life, thereby making the title of “Blessed” official. He is listed in the Roman Martyrology as Beatus Ioannes Faesulanus, cognomento Angelicus—”Blessed Giovanni of Fiesole, surnamed ‘the Angelic.'”

Vasari wrote of Fra Angelico that “it is impossible to bestow too much praise on this holy father, who was so humble and modest in all that he did and said and whose pictures were painted with such facility and piety.”

Death and beatification

In 1455, Fra Angelico died while staying at a Dominican convent in Rome, perhaps on an order to work on Pope Nicholas’ chapel. He was buried in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. His epitaph reads:

When singing my praise, don’t liken my talents to those of Apelles.

Say, rather, that, in the name of Christ, I gave all I had to the poor.

The deeds that count on Earth are not the ones that count in Heaven.

I, Giovanni, am the flower of Tuscany.

— Translation of epitaph

The English writer and critic William Michael Rossetti wrote of the friar: “From various accounts of Fra Angelico’s life, it is possible to gain some sense of why he was deserving of canonization. He led the devout and ascetic life of a Dominican friar, and never rose above that rank; he followed the dictates of the order in caring for the poor; he was always good-humored. All of his many paintings were of divine subjects, and it seems that he never altered or retouched them, perhaps from a religious conviction that, because his paintings were divinely inspired, they should retain their original form. He was wont to say that he who illustrates the acts of Christ should be with Christ. It is averred that he never handled a brush without fervent prayer and he wept when he painted a Crucifixion. The Last Judgment and the Annunciation were two of the subjects he most frequently treated.”

After Pope John Paul II beatified Fra Angelico on October 3, 1982, in 1984 declared him patron of all Catholic artists. “Angelico was reported to say ‘He who does Christ’s work must stay with Christ always.’ This motto earned him the epithet ‘Blessed Angelico,’ because of the perfect integrity of his life and the almost divine beauty of the images he painted, to a superlative extent those of the Blessed Virgin Mary,” Pope John Paul II said.

According to Vasari: “In their bearing and expression, the saints painted by Fra Angelico come nearer to the truth than the figures done by any other artist.”

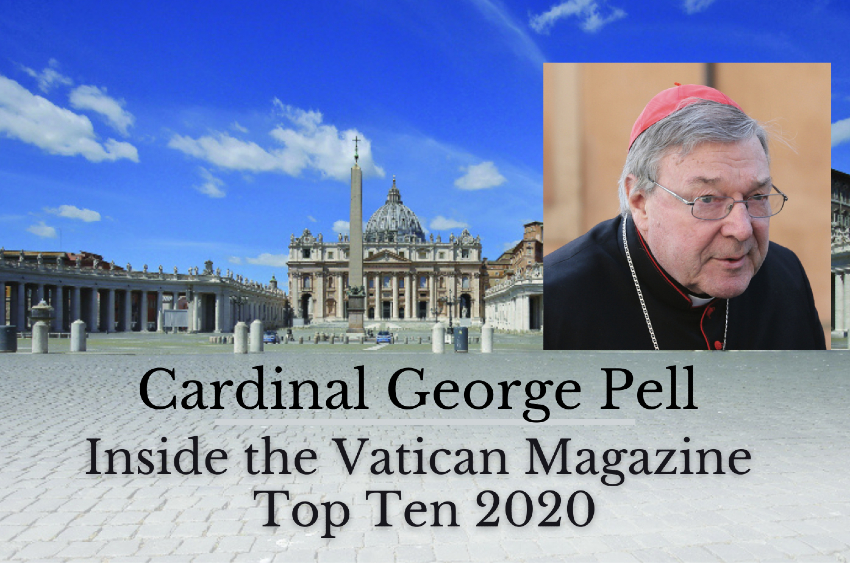

“Top Ten” of 2020: #2, Cardinal George Pell

The year 2020 was one many people say they would like to erase from memory. Yet, many good people did many good and noble things in the year 2020, and Inside the Vatican, this year as in past years, recognizes here just a few of them.

Obviously, these people we have chosen to highlight are not the only people worthy of recognition, but we think each is an example, an exemplar, in differing ways. Of course, there are millions of mothers caring for sick children, millions of fathers caring for their families, thousands of legislators attempting to write just laws, countless artists striving to represent the mystery of divine truth to a world of hardened hearts. We honor them all! Still, we offer these 10 men and women as exemplary men and women, who have lived (and some of whom have died), with courage, honor, charity, tenderness, faith, generosity. In this way, these 10 have shown us the way, no matter how troubled our times may be. —RM

Cardinal George Pell

The Australian prelate was accused, condemned, imprisoned,

then absolved and freed

Top Ten 2020 #2

“My Catholic faith sustained me”

Convicted, then acquitted of outlandish abuse charges, he says there is still “a moral sense even in the darkest places”

Australian Cardinal George Pell, 79, has had one of the more extraordinary careers among the contemporary prelates of the Catholic Church. First an Archbishop of Melbourne, then Archbishop of Sydney and, in 2003, appointed by Pope John Paul II to the College of Cardinals, Pell was tapped by Pope Francis soon after his election to be one of his Council of Cardinal Advisers. The next year, Francis asked him to oversee reform of the Vatican’s financial affairs, which had become quite muddled, if not outright plundered, by mismanagement, or corruption, or both.

Cardinal Pell, the no-nonsense, traditionally orthodox Australian, made a great deal of progress in his role as the Francis-appointed “Financial Czar” (his actual title was Prefect of the Secretariat of the Economy, a post created in 2014) — but he may have also made enemies along the way.

On May 1, 2018, he was notified that he would stand trial on charges that had been filed against him for “historic sexual abuse” — accusations dating back decades — to the delight of many in the press and elsewhere who found his traditional morality appalling.

And thus began his strange odyssey through the criminal court system in Australia, a country which is in the thrall of a particularly anti-Catholic popular culture — more so than the U.S., for example — which had already been exploiting the crisis of clergy sexual abuse to vent its hatred of the Church.

Cardinal Pell could have remained in Vatican City and avoided the media circus waiting for him at home, and the real-life courtroom drama that was to result in his imprisonment; he insisted, however, on traveling to his home country to clear his name.

Cardinal Pell Prison Journal by George Cardinal Pell: 3 volumes in weekly installments on the Ignatius Press website (2020)

Instead, he was convicted in December of 2018 and spent 13 months in solitary confinement before his conviction, widely criticized as outlandish and nonsensical, was unanimously quashed by Australia’s highest court.

He wrote of his ordeal, saying in First Things magazine in August 2020: “There is a lot of goodness in prisons. At times, I am sure, prisons may be hell on earth. I was fortunate to be kept safe and treated well.

“I was impressed by the professionalism of the warders, the faith of the prisoners, and the existence of a moral sense even in the darkest places.”

He says candidly in a December 14, 2020, interview with Italy’s public broadcaster RAI that he suspects he was framed.

“Of course, I suspected it,” he said, noting that he had “some evidence but no proof” of a conspiracy against him.

“It is much worse if someone inside the Church is trying to destroy you,” he lamented. “My family often told me that it would have been different if the Mafia had hunted me, if others, maybe the Masons, had hunted me.”

“All the major figures who have worked together on financial reform, each of us — with very few exceptions, I believe — has been attacked by the media in terms of reputation in one way or another,” he told RAI.

Pell added that he hoped “there is never enough evidence to prove that Vatican money was used not necessarily to bribe directly, but not to poison the public atmosphere against me either.”

“I hope there is no evidence to establish this, for the good of the Church,” Pell remarked.

“We have no evidence yet, but certainly a lot of smoke. We have criminals who have been heard to say: ‘Pell is out of the game. Now we have a highway in front of us.’ “

Cardinal Pell concluded his brief account of his time in prison by saying: “My Catholic faith sustained me, especially the understanding that my suffering need not be pointless but could be united with Christ Our Lord’s. I never felt abandoned, knowing that the Lord was with me—even as I didn’t understand what he was doing for most of the thirteen months.

“For many years, I had told the suffering and disturbed that the Son of God, too, had trials on this earth, and now I myself was consoled by this fact.

“So, I prayed for friends and foes, for my supporters and my family, for the victims of sexual abuse, and for my fellow prisoners and the warders.”

Facebook Comments