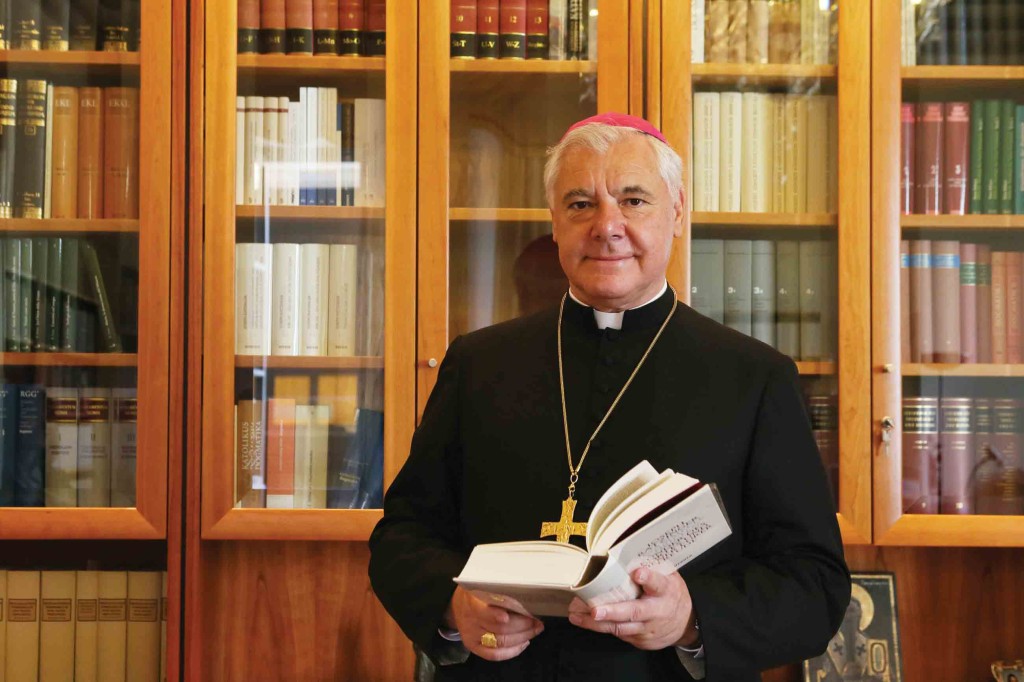

Archbishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller, the new prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, speaks with Vatican journalist Anna Artymiak.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), many questions remain open, many issues unresolved. Pope Benedict himself, as an “eyewitness” of the Council, spoke in early October about the feeling of great joy he had in 1962 at the prospect of a new flowering of Christian faith and life when the Council began, and of how that feeling, over time, changed into a more nuanced, realistic one as it became clear that some of those early hopes were too optimistic or premature. Benedict made these remarks in a touching evening discourse from his apartment window on October 11.

To gain a better understanding of the Pope’s mind, we sat down recently with German Archbishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller, Joseph Ratzinger’s successor at the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, for an extended conversation.

Müller knows Benedict well. The Pope chose Müller to be the editor of the collected edition of all his writings, his Opera Omnia. The 7th volume of this massive undertaking contains Ratzinger’s writing on the Second Vatican Council (“The Theology of the Council: Texts on the Second Vatican Council” [Theologie des Konzils Texte über das II. Vatikanische Konzil]).

Müller is a courageous, creative German theologian. His episcopal motto Dominus Iesus (“The Lord Jesus” but also “Jesus Is Lord”) has a profound theological meaning, he told me. “The expression Dominus Iesus, ‘Jesous kyrios estin,’ is the oldest declaration of faith in the New Testament,” he began. “In the writings of St. Paul it often occurs. Jesus is the Lord. The apostle connects the earthly Jesus, his earthly way as a human being, with the ‘Lord.’ Lord is here another word for God, for Jesus is God. It is a confession of the divinity of Christ. Jesus is the real son of God who has taken on our human nature. I was a professor of theology for 16 years. In the lectures on Christology, this confession is the basis, but also the source, from which everything comes and the central point to which everything leads and is bound together. ‘Jesus is the Lord’: this confession constitutes Christian identity. From that I have taken my motto and from that the document Dominus Iesus has its name.” Then he added: “Also the 95 theses of Martin Luther begin with Dominus Jesus, a fact I like to refer to quite often.”

And so our conversation began…

Your Excellency, fifty years after the Second Vatican Council only a few people recall that Pope Benedict himself took part in it. What was his contribution?

Archbishop Joseph Müller: Joseph Ratzinger became a professor at a very young age. As he was teaching in Bonn (near Cologne), the then-cardinal of Cologne, Joseph Frings, took him to the Second Vatican Council as an expert. There the young theologian Joseph Ratzinger prepared many speeches for Cardinal Frings, who was a moderator of the Council, and he gave theological lectures on important themes to the German-speaking bishops.

In this way, a considerable amount of his thought made its way into the texts of the Council, especially with regard to the understanding of revelation.

The revelation of God is not only the sum of individual truths, but God reveals himself in his son Jesus Christ, in his Holy Spirit, and therefore God is for us human beings truth and life. We as mortal beings, as creatures, want to perceive the truth. We want to try with our will to do the good, and by doing good, to reach a deeper life, namely, eternal life. These lines of thought have gone into Dei Verbum.

Also, in Lumen Gentium, the document on the nature of the Church, there are many contributions by Joseph Ratzinger. It is important that the Church is understood as a Mysterium. It is in God’s saving plan that the Church is founded. He calls from men those who believe in his words and makes them one people; he forms them into the body of Christ, Corpus Christi, and he makes us a Holy Assembly of Priests, a temple of the Holy Spirit.

Archbishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

But even though Joseph Ratzinger proposed the concept of Corpus Christi in Lumen Gentium as a way to understand the Church, another concept, that of the People of God, became very popular.

Müller: He who has studied theology knows that this concept of the People of God was not taken from sociology or from politics; therefore, to see in it the idea of a Church under the rule of a worldly government is wrong…

In Christ, the Church is the sacrament, symbol and instrument of the salvation of the world.

The Church is, in Christ, mediator of salvation through the sacraments, through the preaching of the word of God, through the pastoral care of the bishops.

In the Old and New Testaments, many images can be found which show this relation of God to the faithful: the flock and the shepherd, the vineyard and the wine-grower.

“People of God” appears mainly in the Old Testament and presents the Chosen People of God: Israel. Through Jesus Christ, through the Incarnation, there is an intensification in the relation between God and his people. We are taken into the relation of God to himself, into the community of Father, Son and Spirit.

Already the Father of the Church, Cyprian of Carthage, speaks in this sense about the Church as the “people of God the Father”…

As the Son of God, who became man, has made the Church his body, the Church is not only a people with a vocation, but she is the body of Christ. He is the head, we are the members. He makes us a unity, we are taken into the human nature of Christ. Therefore we have a share in his relation as a son to his father; we are ourselves sons and daughters of God.

And the Church is the Temple of the Holy Spirit. The temple is an image for the presence of God, which fills us human beings. He is not present like he would be in a pagan temple, caught in one place, but “temple” means the whole Church and in the center of this Church lives the Holy Spirit who permeates all with the love of God.

Therefore it is important not to set in opposition the concept of “People of God” to the concept “Body of Christ” when interpreting the Council. The Church is the People of God, unified by the triune God. She is the Body of Christ. She is the Temple of the Holy Spirit.

All are called to work together in the life of the Church. God himself gives to the Church its shepherds and preachers, bishops, priests, deacons, and he gives to the baptized their charisma so that they can help build up the Church of God, the body of Christ, in love.

Therefore its is wrong to say that the Church consists of individual groups and parties that fight and argue against each other.

It is also wrong to think that the Church of Rome is only one party amongst many others. This is a view of the Church that has its place neither in the New Testament nor in the ecclesial tradition, nor in the valid teaching of the Church. This is no Catholic view of the Church, but an anti-Catholic one which would destroy the Church, if one gives in to it. In many countries we now have the problem of a dwindling consciousness of the Church unified in Christ. Instead, interviews are made against one another, and some irrelevant opinions are uttered. When we as Catholic Christians fight against each other, then only those groups who are against the Church are happy about it.

In his book Jesus of Nazareth, does Benedict continue the line of thought begun in Dei Verbum?

Müller: In theology and in spiritual life we can learn to understand the traditional doctrines of the faith better and discover new aspects in them. Even the individual Christian can reach a deeper understanding of the wealth of revelation in the course of his life. Our human thought is limited; we think in a discursive way, we get nearer to the meaning of something step by step — or we don’t. We often remain at a superficial understanding.

In Catholic teaching there is no “development” in the sense that we get from one content to another content that contradicts the original one. Dei Verbum also is an ecclesiastical, man-made document of teaching and therefore it can always be understood and explained in a more profound way. But Dei Verbum formulates something absolutely basic for the Catholic faith: Scripture, Tradition and the Magisterium cannot be set in opposition. There is an inseparable connection between the presence of God’s word in Holy Scripture, in the Apostolic Tradition and in the Magisterium of the Church, which is given to us by the succession of the bishops from the Apostles.

Archbishop Müller during the interview with Polish journalist Anna Artymiak.

In many statements about Joseph Ratzinger and the Council, the idea is spread that he was more or less an “enemy” of the Council. Is this true? Was he against Vatican II?

Müller: This may be the opinion of somebody, but it is entirely wrong. Something like that mostly comes from extreme groups fighting against each other. Those are mostly people who say that the Council is a break with the past — for some this break is something positive, for others something negative. Both sides are wrong, because it is not a question of a break, but a proof of the continuity of the Church’s teaching.

I think that nobody knows the Council in its history and teaching better than our Pope Benedict XVI. For people who talk about a break it is not the Council that matters, but their own personal interests. They want to make use of the Council for ideological aims that are not compatible with the Catholic faith.

The Pope is appointed by Christ. Like Peter he is the rock; he was given the power of the keys, the authority to bind and to loose. The Roman Pope, the Bishop of Rome, is the everlasting principle and foundation of the visible unity of the Church, also of the unity with Jesus Christ. Therefore it is a contradiction to think that the Pope is standing against the teaching of the Church as expressed in the Second Vatican Council. I strongly refuse such opinions, because they are nothing but propaganda — lies.

A fundamental theme of the Council was the reform of the liturgy. As a young professor, Ratzinger wrote The Spirit of the Liturgy, and as Pope, in 2007, he promulgated the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum. Was this a reversal of prior progress?

Müller: In the Church we must not follow a blind ideology of progress. It is of no importance to be conservative or progressive according to any standard whatsoever. Who sets the standard for this? What does it really mean? For human thought and human reason it is important to stick to the essential facts.

The evil ideologies of the 20th century also regarded themselves as progressive and denigrated faith as medieval. Today one realizes what disasters they have produced on the level of morals and reason.

It is decisive to do the good and to perceive the truth, and the truth is not dependent on the factor of time but on the willingness of man to open himself to the word of God and to accept the moral law that God has given us and to realize it in one’s life.

There are misuses of liturgy, rendering it banal and trivial. But the cause for this does not lie in the Second Vatican Council but in a wrong theological concept. If I don’t see Jesus as the Son of God, who has become man, then liturgy is but a collection of some rites and signs, and it only serves to foster the sense of community of the people or their esthetical sense, similar to a concert. Beautiful sounds and visual impressions, which speak to the sentimental side of man, that we are once again sitting together happily and are feeling good – this is not the essence of liturgy!

Its essence is the presence of God in the sacrament through the Incarnation of the Son and the sending of the Holy Spirit. It is only in this perspective that the liturgical signs are filled with meaning; only in this way they become signs, actions and rites of the Church that are in their depth supported by divine life. The hymns and the music raise our hearts up to God and the robes underline the importance of what happens in the service.

Liturgy is no banal event, because its aim is the glorification of God and the salvation of man. This salvation is passed on to us in the sacraments, but in a similar way also in other forms of worship, in the sacramentals, the services of prayer, the way of the cross, processions, pilgrimages. In the different forms of worship we can experience: God is with us, God, Christus Emmanuel, God in our midst. We are the People of God on pilgrimage, we know where we come from, which is the way and where we go, for Christ says to us also today: “I am the way” — which means the way that connects the beginning and the destination.

In Summorum Pontificum the Holy Father has permitted the form of the liturgy as it is found in the Missale of Pope John XXIII as an extraordinary form, without calling into question the ordinary form of the Mass. In the history of liturgy there are alterations again and again, which don’t, however, affect the substance of the Mass but bring improvements. It is clear that the Eucharist also has a catechetical aspect, but that is not in the foreground. The fundamental dimensions of the liturgy — adoration, praise, glorification, preaching — have to be put into the right balance. It is not good when the priest preaches three sermons: a long introduction, then he preaches and at the end says a lot of things that have nothing to do with the Mass. This means making the Mass banal and trivial. This is what the Holy Father wanted to draw attention to.

From the Extraordinary Form we can learn to stand before God full of reverence — such aspects are to become clearer again, also in the Ritus Ordinarius. The people are to be sensitized that one doesn’t just walk round in the church as if it were a museum, but that one genuflects before Christ in the Most Holy Sacrament; that we take the holy water knowing this is holy ground on which we are standing. In a church we can experience the presence of God our Savior in a special way. Here the Word of God that became flesh — Jesus Christus himself — is truly, really and essentially present among us.

Archbishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller.

Another fundamental issue at the Council was ecumenical dialogue. Then, as prefect, Ratzinger published the Declaration Dominus Iesus…

Müller: There are very many reactions, among them also some not very inspired ones. The latter often were the echo of some reports in the media, which were not able to cope with the contents and aims of this document. It is hard to talk about this with those who have not read the text of Dominus Jesus. Beyond special theological problems, the document in fact expresses what is the foundation of Catholic belief: There is only one God in the three persons of Father, Son and Holy Spirit; God, the Son, has taken on our human flesh; in his human nature he has taken up all men and led them into the relation with the threefold God. Through Christ we are sons and daughters of God and may enjoy the friendship and love of God in the Holy Spirit. Therefore also there is only one Church; only one Church can exist. When we speak in the plural of different churches, then we mean the one Church of God in Corinth, in Rome, in Cracow — wherever. These are the different churches in which the one Church of God is present, that appears in the communio ecclesiarum. These different churches are not, however, different denominations standing against each other, having a different confession or a different basic understanding of what really is the Church of God.

The separations in Christianity have brought forth varying concepts of Church in the different communities. Otherwise they would not have separated from one another.

From the Catholic point of view, the Church in her visible form exists as a community of individual churches which are led by legitimate bishops in unity with the successor of St. Peter.

In such a context it is not impossible that in other Churches, in Orthodox Churches, that essentially share our fundamental understanding of the Church, and in ecclesiastical communities of Protestant origin, that have a totally different understanding of the Church, there are nevertheless essential elements of the Church: baptism, Holy Scripture, belief in the threefold God and many other basic elements of revelation — elements that are focused, however, on the full communio with the visible Catholic Church. Because non-Catholic Christians have a different starting-point, we cannot presume that they share our view. From the Protestant point of view, the aim is not the visible unity of the Church, as is the case for us Catholics.

Therefore it doesn’t make any sense at all to think the text Dominus Iesus had hindered the ecumene. On the contrary — it was only made clear what had always been the Catholic point of view. It’s not the question of taking something away from others or depriving them or pushing them back. It’s simply the question of clearly naming the differences.

From the Catholic point of view this is important: The ecumene and ecumenical theology have the task to name these differences or contrasts and, where possible, to diminish them or to overcome them, so that a visible unity in the confession, the sacraments and the pastoral work of the Church may be achieved. Dominus Iesus is an honest description of facts. For theology and for everything we do we can only take the facts as our starting-point, not any illusions.

The Council also addressed the question of freedom of religion…

Müller: According to the statements of Dignitatis Humanae it is clear: religious freedom means that every person, because of natural law, decides in his conscience what he accepts as truth; that he may also voice his religious convictions, also in community with others and in public. The state is not allowed to compel anybody to act against his conscience.

Today it is a problem in some states that in the name of freedom, self-determination and emancipation, it is thought that one can force believers into actions that are against their conscience. For instance it is said: By law we make it a duty in a Christian hospital that even a Christian doctor must perform abortions. If this is not done, we withdraw state support from this hospital. This is quite an obvious attack on religious freedom. This is a step back into a totalitarian way of thinking. For no state has the right to compel anybody against his conscience to do something that he thinks is evil, bad and sinful.

The Liberals of the 19th century understood something different by religious freedom, namely that somebody has the freedom in relation to God to construct his own religion. This the Church has always refused up till today, for we are obliged to answer to God in our conscience. Therefore this — wrongly so-called — religious freedom cannot be accepted. It is obvious that, if God exists, man is obliged to him in his conscience. What I said before about religious freedom refers to the religious freedom in relation to other people. We must not force others to act against their conscience. In relation to God, however, religious freedom is the fact that we are free and uncompelled to obey the word of God.

Did the Pope offer you some advice on being prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith?

Müller: No, he didn’t say anything. The Holy Father doesn’t interpret or correct his collaborators in this way. We are all quite free. In this respect I think that we should simply follow Pope Benedict’s line of thought.

Facebook Comments