Archbishop Claudio Maria Celli on January 11 concelebrated a Mass at Santa Maria in Transpontina, near St. Peter’s, in memory of American Cardinal John P. Foley, who died on December 11, 2011

There were mostly Americans and a few TV reporters in the church of Santa Maria in Traspontina on Wednesday, January 11, a sunny, cold morning in which we prayed for Cardinal John Patrick Foley a month after his death.

Archbishop Claudio Maria Celli, Foley’s successor as president of the Pontifical Council for Social Communications, delivered the homily. With him as concelebrants were Monsignor Pierfranco Pastore, for years an official at the Pontifical Council of Social Communications, and Father Federico Lombardi, director of the Vatican TV Center as well as head of the press office. (It is thanks to Cardinal Foley that the Vatican Television Center exists, allowing the world to see the Pope on TV.)

Celli told about the last meeting of the entire family of the Council for Social Communications with the cardinal in February of 2011. Foley was already sick.

“We felt,” Celli remembered, “like persons working in the field of communication gathered around a teacher who not only communicated, but testified how suffering can have expressive ways that not even the sum of all the apparatus of the new technologies can match.

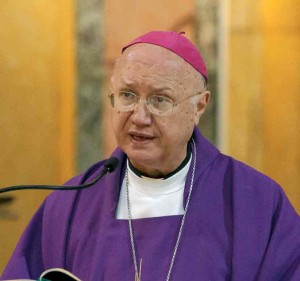

Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano, apostolic nuncio to the United States, reads a message from Pope Benedict XVI at the funeral Mass for U.S. Cardinal John P. Foley in the Cathedral Basilica of Sts. Peter and Paul in Philadelphia December 16 (CNS photo)

“He came to give us the last, most important lesson, giving all his best, as a communicator, of course, but even more as a witness and a faithful servant of the Word,” Celli continued. “We have not forgotten that lesson, not due to any merit of ours, but simply because it is not possible to forget such lessons.”

A lesson was also his last live comment for the radio of his city, Philadelphia: the Mass for the beatification of John Paul II on May 1, 2011.

John Patrick Foley was perhaps the first to devote himself to the media at the Vatican with total dedication. Of course he had opponents and supporters — the Vatican is no different from any other place where you make decisions and choices.

“I am happy to do this service for Pope John Paul II,” Foley said about the Beatification Mass commentary. “It is a privilege to be able to make this comment on his beatification after having had the sad task of making comments at the time of his death and burial,” he told his colleague who conducted the program. (I use the word “colleague” because Foley had been a journalist: he was for a number of years the editor of the Catholic Standard and Times, the newspaper of the archdiocese of Philadelphia.)

Foley earned his degree in journalism at Columbia, and his degree in theology and philosophy at the Angelicum. For 25 years, from the beginning of 1984 until 2009, he was the voice that on Christmas Eve accompanied American Catholics at the Midnight Mass from St. Peter. This was also a reason why, on November 18, just weeks before his death, he was named “Man of the Year” by the Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia, the association of all broadcasters in the city. Perhaps this recognition was less than some others that this man of the Church had received, but the cardinal appreciated it greatly.

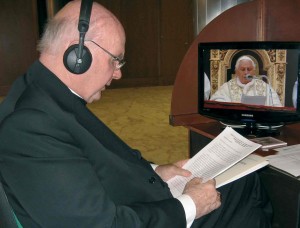

Cardinal John P. Foley provides live commentary for Benedict XVI’s Easter blessing “urbi et orbi” at the Vatican on April 12, 2009 (CNS photo)

He had left his post as grand master of the Order of the Holy Sepulcher not long before. That post had nothing to do with chivalry, but with real works of charity and mediation for peace in the Holy Land. After one of his last trips he granted several interviews. The theme was always the same, because as a communicator he knew how to “insist.”

“We should be more aware of the situation of Christians in the Holy Land, who are the successors of the first followers of Christ, who live oppressed and suffer as a double minority,” Foley said. “They are a minority within the Jewish population in Israel but also in the Palestinian population, the vast majority of which are Muslims.”

And for this reason, he urged Catholics to “help them — help their schools, help their parishes, help the University of Bethlehem, which is a Catholic university created in a society with a strong Muslim majority. The Catholic schools also accept Muslims, thus contributing to interreligious comprehension and, hopefully, to a viable peace between Muslims, Jews and Christians.”

Foley’s first TV appearance was in 1954 with Edward R. Murrow on See It Now. “It was a 10-second soundbite, but in ecclesiastical terms, one could say that they are now a relic.”

That was another one of his characteristics: a sense of humor. He always had a smile on his lips, and his big blue eyes stared out at you with the wonder of a child. Those eyes always had a great impact on television.

For 23 years he headed the Pontifical Council for Social Communications. It was not easy to manage the media when John Paul II revolutionized the system, with technology advancing and journalism changing. His speeches were always American-style, dry and clear. Once, during a conference in the Vatican press office, he criticized the bad habit of some men of the Curia of making anonymous statements as “Vatican sources.” He said everyone who talks has to assume his responsibilities. This honesty is too often “forgotten.”

When Foley passed away, Pope Benedict XVI said he hoped the legacy of the late cardinal would inspire others to make the Gospel known through mass media.

Foley died December 11 in Darby, Pennsylvania, after a battle with leukemia.

In a telegram the next day to Archbishop Charles Chaput of Philadelphia, the Pope expressed his sadness and condolences.

“I recall with gratitude the late cardinal’s years of priestly ministry in his beloved archdiocese of Philadelphia, his distinguished service to the Holy See as president of the Pontifical Council for Social Communications, and most recently his labors on behalf of the Christian communities of the Holy Land” as grand master of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulcher of Jerusalem, the Pope wrote.

The Pope prayed that the cardinal’s “lifelong commitment to the Church’s presence in the media will inspire others to take up this apostolate so essential to the proclamation of the Gospel and the progress of the new evangelization.”

The cardinal combined his journalistic training, professionalism, and a friendly and approachable manner with his wisdom, humor and “passion to share the good news of God’s infinite love for every person,” Archbishop Celli said at the time. Cardinal Foley promoted dialogue within the Church about communication, culture and media, and called on professionals to seek the highest standards in their work, he said.

Msgr. Paul Tighe, secretary of the communications council, said Cardinal Foley was deeply committed to “helping people who maybe weren’t so close to the Church to understand better the Church that he loved so much. His great sensitivity was finding a language, and a way of speaking, a way of helping them to understand the Church and to maybe overcome the little misunderstandings that could often color their attitude toward the Church.” Although Msgr. Tighe never worked directly with the cardinal, he said “his was one of the friendliest and most encouraging faces and presences around the Vatican.”

“The thing that always struck me was while people had enormous respect for him, they had an even greater affection,” Tighe said.

Cardinal Foley was a caring listener who took the time to send personalized and thoughtful notes and gifts, the Irish monsignor said.

“As he was leaving Rome he went out of his way to give me a gift of something he had which was a signed letter by the Irish patriot Michael Collins,” who was killed during the Irish Civil War in 1922. “It was the attentiveness to say, ‘I know that you would like this’ that made the man,” he said.

Marjorie Weeke, who met Cardinal Foley when he worked as a reporter covering the Second Vatican Council from 1963 to 1965, recalled when Blessed John Paul II named him president of the Pontifical Council for Social Communications in 1984. She said he was both surprised and excited to head the office because “he was such a media person, and right away he called some of the (news) bureaus and asked if he could be helpful to them.”

Weeke, who worked at the council from 1971 to 2001, said the cardinal was always trying to make the Church more accessible and understandable to the media.

Whenever a papal document came out, he’d write up a summary of what it said and meant so “it would be easy for the press to read. It was helpful, that’s why the journalists liked him so much, and he was always available for interviews for anybody,” she said.

Under the cardinal’s tutelage, the council, which dealt with television and photo journalists’ access to the Vatican, gradually chipped away at Vatican reticence to allowing audiovisual journalists anywhere near the Pope for fear their presence would be a disturbance, she said. Yet “little by little we expanded to get media closer to the Pope,” and now they are stationed on special platforms or areas off to the side or positioned at a short distance in front of the Pope, she said.

One thing that made Cardinal Foley so special, she said, was that despite his career climb, “he was always a priest” — a vocation he loved very much. Even though he didn’t have time to do the kind of pastoral work he was used to doing back in the United States, he still did Confirmations, celebrated Mass, blessed marriages or heard confessions as often as he could.

“People felt they could talk personally to him,” and he was able to touch people’s hearts even over the air when they heard him doing commentary during the Pope’s Christmas Midnight Mass, she said.

Weeke recalled one man in Australia who wrote to Cardinal Foley, telling him he was the reason for his conversion to Catholicism after hearing his Christmas broadcast, which often generated fan mail praising his warm, up-close-and-personal style of commentary.

His deepest passion was communicating. That’s his legacy. Together with his smile.

Facebook Comments