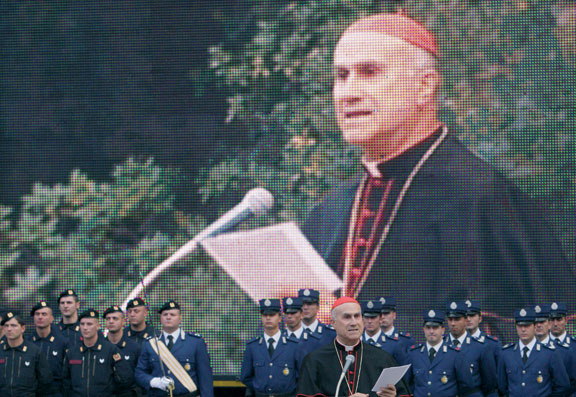

Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone at Castel Gandolfo on September 27, 2008, when the Vatican’s Gendarme Corps celebrates the Feast of St. Michael the Archangel, their patron

June 3, 2012

“Christian life is a journey, it is like hiking up a mountain path in the company of Jesus. With these precious gifts [of the Holy Spirit], your friendship with Him will become ever closer, and ever more true.”—Pope Benedict to young people in Milan receiving their confirmation on Saturday, June 2, during a World Day of Families celebration

At least one more person is still releasing secret Vatican documents, according to an article published in Rome’s La Repubblica newspaper June 3, and one of those documents is a letter written by American Cardinal Raymond Burke to the Cardinal Secretary of State Tarcisio Bertone, expressing perplexity for the fact that he was not informed about an important liturgical decision taken without his knowledge.

And the person who has revealed these three documents claims to possess “hundreds” of other, not-yet-published, Vatican secret documents. If this is true, more revelations may lie directly ahead.

In La Repubblica’saccount, the source releasing the new documents, who is evidently someone who works in the Vatican, aims to strike two highly placed Vatican officials very close to the Pope: Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, Benedict’s increasingly controversial Secretary of State, who is now 77; and Monsignor Georg Gaenswein, 55, one of Benedict’s two personal secretaries.

U.S. Cardinal Raymond L. Burke heads the Vatican’s highest court — the Supreme Court of the Apostolic Signature. He is pictured at the Vatican in a 2010 file photo. (CNS photo/Catholic Press Photo)

The attacks on Bertone, according to generally reliable sources, stem from the fact that Bertone has profoundly offended a number of other cardinals by the way he has exercised his authority. These sources say Bertone, for example, has written letters to other cardinals telling them Pope Benedict wishes them to do something, like step down from an office they hold; however, the sources say, when the cardinals involved have directly contacted the Pope, the Pope has said the wishes expressed in the letters from the Secretary of State were not, in fact, his wishes; the cardinals have, therefore, stayed at their posts. (Note: I have not been able to confirm that this is what actually happened; I can only say with certainty that this is what is being said happened, and that this is being held out as a key reason a number of cardinals and other high-ranking prelates have turned sharply against Cardinal Bertone.)

Why Monsignor Gaenswein is under attack is not entirely clear. But the La Repubblica source claims that the contents of letters signed by Gaenswein are not being revealed because they would be “offend the person of the Holy Father” (“non pubblichiamo in modo integrale per non offendere la Persona del Santo Padre”) and that the letters regard “shameful cases inside the Vatican” (“vergognose vicende all’interno del Vaticano”).

One letter, dated January 16, was sent by Cardinal Burke, an American who heads a Vatican department, to the Pope’s Secretary of State, Bertone. Burke complains that a decision regarding a liturgical matter was taken without consulting his office, which is responsible for such matters. On the letter, there is a brief note in the Pope’s own handwriting, saying that the letter should be sent back to Cardinal Bertone and that Burke’s suggestions and concerns should be taken into consideration.

The person who sent Repubblica the documents also provided two letters signed by the Pope’s private secretary, Monsignor Georg Ganswein. The newspaper said those letters had everything but the letterhead and the signature whited out. The person who sent the documents to the paper said Bertone and Gaenswein were “those really responsible for this scandal.”

Butler Faces Six Years

Meanwhile, Paolo Gabriele, the papal assistant, has been accused inside Vatican City of aggravated theft, a crime that, under Vatican law, is punishable with a prison term of 1 to 6 years, a Vatican judge told journalists in a press briefing on June 5.

Paolo Papanti-Pelletier, the judge, said under the terms of the Vatican’s 1929 treaty with Italy, a person found guilty and sentenced to jail time by a Vatican court would serve his term in an Italian prison.

The judge also said that while Gabriele remains detained in a 12-foot-by-12-foot room in the Vatican police station, he was allowed to attend Mass June 3 in an unspecified “Vatican church.” Two gendarmes accompanied Gabriele to the church, but he was not required to wear handcuffs, the judge said. The judge briefed reporters on how the Vatican criminal justice system works, in view of the investigation currently under way regarding Gabriele and his alleged involvement in the publication of hundreds of private letters and notes to or from Pope Benedict XVI and top Vatican officials.

Life inside the Vatican is regulated by the Code of Canon Law, but also by a set of civil and penal laws and processes adopted from Italian law and partially adapted to fit Vatican circumstances, he said. Papanti-Pelletier said that after an initial investigation by the Vatican gendarmes led to Gabriele’s arrest May 23, the butler was questioned by a Vatican investigative judge and formally accused of aggravated theft. A more formal questioning of the suspect by the investigating judge, Piero Antonio Bonnet, began June 5, said Papanti-Pelletier, who has not been involved directly in the case.

While the investigating judge serves as the chief investigator, whose responsibilities include questioning witnesses, he must also make the critical determination of whether there is enough evidence to bring the accused to trial. If he decides there is not, the case is dismissed. Otherwise, he formally indicts the accused. Papanti-Pelletier said there are several factors that make a theft “aggravated” under Vatican law. The first is that the person committing the crime steals from someone with whom he had a relationship of trust. A second factor would be if the accused worked with another person to commit the crime.

If two or more aggravating factors are found to be present, Papanti-Pelletier said, the possible prison term would be from 2 to 8 years. Additional charges — like receiving stolen goods or revealing state secrets — could be added as the formal questioning proceeds, he said.

The initial questioning stages of the investigation are conducted behind closed doors to protect the privacy and reputation of the accused and to “guarantee the rights of others who may be implicated,” the judge said.

However, he said, if the case goes to trial, the hearings in the Vatican’s Tribunal Palace, behind St. Peter’s Basilica, would be open to the public and the press. However, he added, the courtroom is not enormous, so only a limited number of people could get in.

The public trial would be held before three judges, just as Italian trials are, he said. There is no jury of one’s peers.

While all witnesses testifying at the trial take a formal oath to tell the truth, Papanti-Pelletier said under Vatican law a defendant is not asked to swear to tell the truth and he may refuse to answer questions on the grounds that the response could incriminate him. Papanti-Pelletier said that while the Vatican has no jail, it does have four “secure cells” — the 12-by-12 rooms, which are equipped with a bed, desk and bathroom. There is a crucifix on the wall, but no television. And those detained eat the same meals prepared for the gendarmes on duty.

According to Vatican law, a person accused of a crime can be detained for 50 days before being formally indicted and the period can be extended another 50 days if the investigation is deemed sufficiently complex, he said. While the Vatican code does not speak specifically of “house arrest,” it does say the accused could be detained anywhere on Vatican property, so it is possible the 46-year-old Gabriele eventually could return to his Vatican apartment with his wife and three children.

Paolo Papanti-Pelletier, a judge in the Vatican court system, leaves the Vatican press office after speaking to the media June 5. In the wake of the arrest of Pope Benedict XVI’s private assistant, Paolo Gabriele, the judge spoke to the media about how the Vatican’s criminal justice system works (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

Papanti-Pelletier said Pope Benedict XVI can intervene at any time to halt the process and release or forgive the accused, although it would be unusual for a pope to intervene before the investigatory phase has been completed.

The judge said the investigatory phase is taking time because of the amount of documents that have been leaked and because Vatican investigators are still determining whether or not all of them are authentic. Papanti-Pelletier said Vatican law treats all laypeople, religious and clergy equally, unless they are cardinals. “Princes of the Church can only be judged by their peers,” which would be the Vatican’s supreme court. The president of the three-member court is U.S. Cardinal Raymond L. Burke, and the members are French Cardinal Jean-Louis Tauran and Italian Cardinal Paolo Sardi.

On June 4, Cardinal Bertone told Italian state television that the leaks were “attacks,” which he described as “carefully aimed” and as “ferocious, destructive and organized.”

Jesuit Father Federico Lombardi, Vatican spokesman, told reporters June 5, “With the large number of documents already out there, we should not be surprised there are more in circulation being used to maintain the tension or keep attention on this matter.”

Facebook Comments