God’s word will quench the thirst of your soul

By Anthony Esolen

Detail of the mosaic in the apse of St. John Lateran with the cross from which the baptismal water flows for all to drink

Lately, I’ve been providing the notes for my new translation of Augustine’s Confessions (forthcoming from TAN Books), and something has struck me with especial force. It’s that Augustine apparently breathed the words of Scripture, especially those of Genesis, the Psalms, the Gospels, and the letters of Saint Paul. I don’t just mean that he often refers to them. I mean that he hardly has to refer to them at all: they rise naturally to his mind, regularly, always, because in a wondrous way they seem to be in accord with everything a wise man can say about human life and human nature, fallen as it is, and glorious as God intends for it to become in those who will accept the grace He offers. It is like a source of ever-springing musical airs to a Bach or a Mozart: not just a strand of melody here or there, but a living and all-penetrating world of music and meaning.

Imagine what it is like to drink deeply from such springs! I am but a beginner by comparison, a small boy who crouches down and cups his hands to sip from the clear pool.

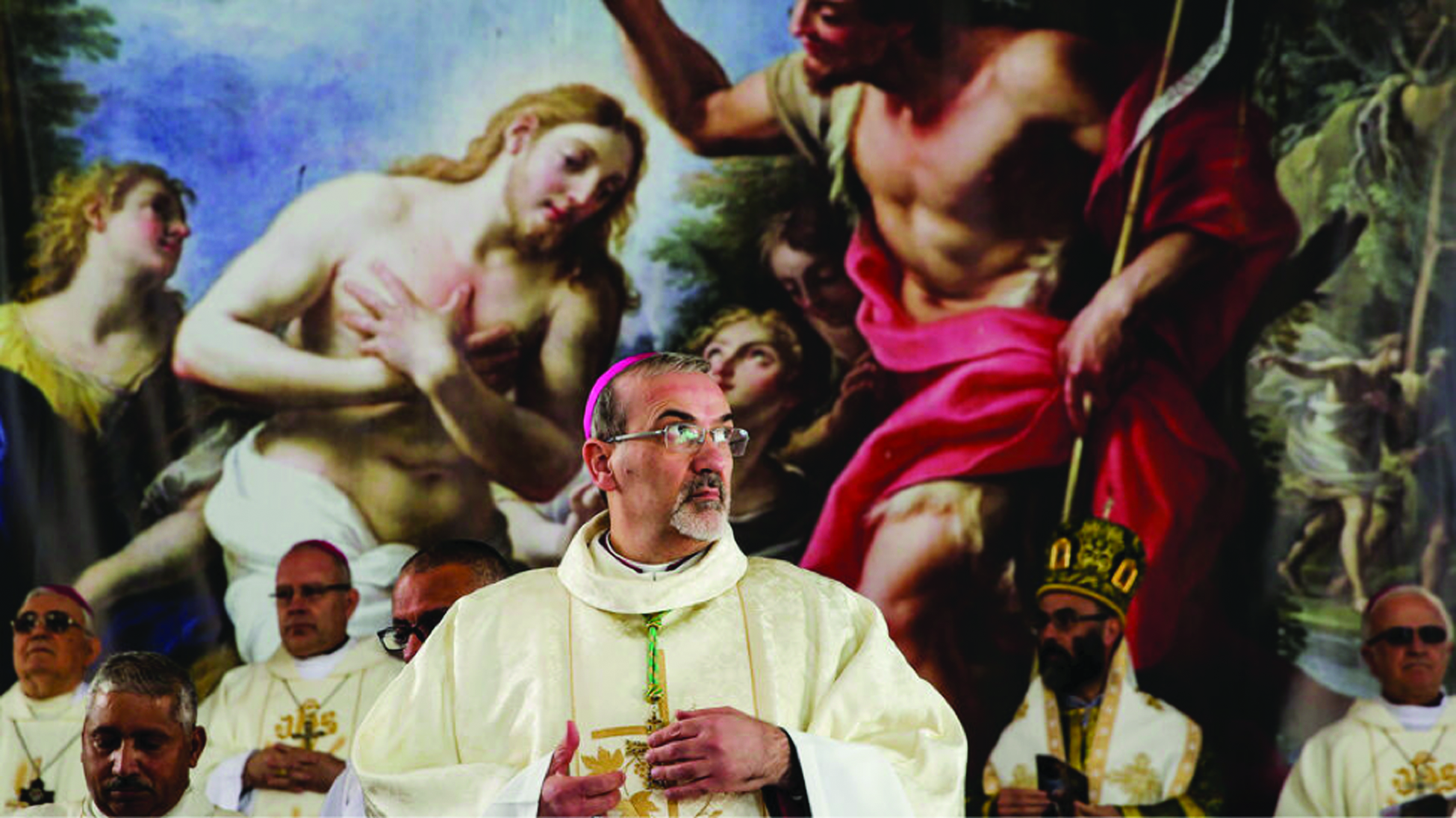

If you go to St. John Lateran in Rome, you may see a mosaic of a lovely rushing river, and deer that drink from it. My family and I saw that mosaic long ago, in 1998, when we were traveling through Italy, and I heard a tour-guide explain it to the people he was leading. “The deer are symbols of the apostles,” he said. They weren’t. I told my family what they were, straight off, and I said it loud enough for some in that entourage to overhear me. The deer were an echo of the first verse of Psalm 42: “As the deer longs for the running streams, so my soul longs for you, my God.”

That was one of Augustine’s most beloved verses. He knew from bitter experience how the water that the world has to offer smacks of salt, and does not satisfy. We drink of that water, and we thirst all the more, because the salt burns our throats and leaves them raw. But he who drinks of the water that Christ will give us, as the Lord said to the woman at the well (Jn. 4:14), will have springs within him, rushing up into eternal life. That is the water we long for, like the deer.

Augustine found that water both in Scripture and from Scripture. That is, the word of God in Scripture does quench the thirst, but it also awakens and arouses the thirst and fills it with longing for the reality toward which it leads us. The psalmist says that he meditates upon the word of God, and that has made him wiser than his teachers (119:99), but at the same time it causes him to desire more and ever more. The true wisdom does not make us fat and self-satisfied. It urges us onward. “Seek my face,” says the Lord, and the psalmist replies from the heart, “Thy face, Lord, will I seek” (27:8). If we inquire of the Scripture with a humble heart and an open mind ready to learn, if we inquire of it with love, allowing ourselves to be little so that the Lord may make us great, we will be like the deer that the artist portrayed at St. John Lateran, thirsty, but calm, peaceful, filled.

Augustine wasn’t always like those deer, longing for the running streams. Or rather, he was like them in his being parched, but he did not know where the good water was; or he did know where it was, but he was too proud to seek refreshment there. And this is our condition when we look to Scripture to confirm what we already believe for other reasons — personal, political, philosophical, or even theological reasons. Deer will naturally be drawn to the water.

But man, possessed of a free will, can wrench himself away from his own proper nature, and persuade himself that something other than God, the God of truth and beauty and love, can satisfy him; or he makes into God what he believes already does satisfy him, changing “the glory of the incorruptible God into an image made like corruptible man” (Rom. 1:23), even an image that looks like himself.

Then we become like the Pharisee who proudly goes to the temple to pray, saying that he is grateful to God for having made him not “as other men are,” such as the tax collector standing far off. Then that Pharisee goes on to enumerate the ways that other people are bad, and the ways he is good (Lk. 18:10-14). The Pharisee, essentially, is praying to himself about himself, while the tax collector simply beats his breast and begs God for mercy.

To approach Scripture as a deer that longs for the running stream is to open yourself to it, knowing that it brings refreshment that we cannot bring for ourselves. But because we cannot, we may well shy away from the water — or Satan, that liar and murderer from the beginning, may whisper into our ears something like what Augustine thought, that the Scriptures were beneath his notice. For Augustine was trained up as a man of letters, and he expected to find in Scripture his own kind of eloquence, just as someone of our time might expect to find in it his own politics, his own view of the relations of man and woman, his own economics, his own scientism — whatever Egyptian stew we are fond of, seasoned with garlic and onions and leeks, and not the manna, the bread of heaven (Num. 11:5).

The children of Israel had already tasted of the manna, but not with grateful hearts, so they grew weary of it. Consider: God gives us heavenly food, even his word, so that the psalmist can cry out, “Taste and see how good the Lord is!” (Ps. 34:8). But we have proud stomachs. We want the stewpots of Egypt. We want the flesh that tastes of death. Only after Augustine gave up his pride did he find in Scripture an eloquence infinitely more profound than any that Cicero ever knew, humbling and exalting at once. I dare not say, as a notorious Swiss theologian once said, that much of Scripture is “trash.” No, it’s the attic of the fallen human person that is full of trash, the trash of sin, certainly, but also the trash of current fads, political programs, social climbing, self-presentation, what all the smart people “know,” and so forth. Do not give me, I might have said to that man, your best champagne at Biarritz. I want the living waters.

And, God, give me the greater thirst, that I may drink the more deeply. Let me long to know you better, that I may better long while I am here, and more plentifully enjoy the sight of your face at those ever-rushing streams beyond.

Facebook Comments