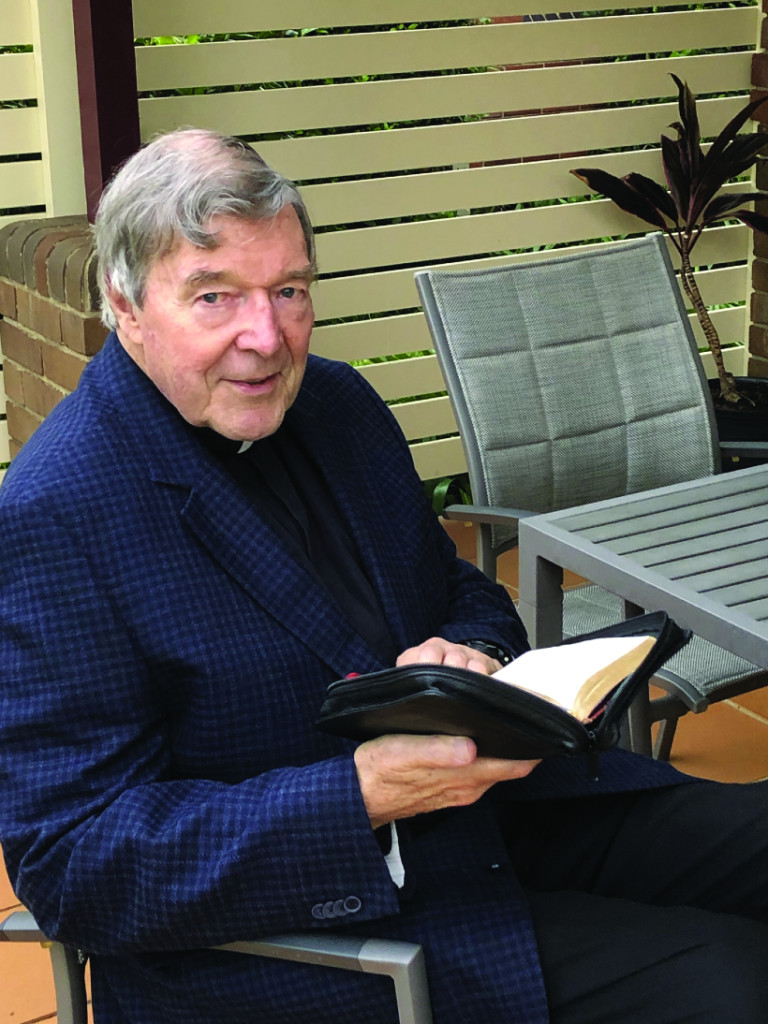

Conviction Overturned: Australian Cardinal George Pell has been released from prison after his conviction on charges that he abused two boys was overturned by Australia’s highest court. Pell here relaxes on the grounds of the Seminary of the Good Shepherd in Sydney April 9, 2020. (CNS photo/courtesy Archdiocese of Sydney)

After 409 Days in Solitary Confinement, the Former Head of the Vatican’s Secretariat for the Economy is Acquitted of “Historic” Sexual Abuse Charges

By Christina Deardurff

A cardinal of the Catholic Church, convicted in Australia last year of disgraceful crimes of sexual abuse, spent 409 days in solitary confinement in two different prisons. He underwent two trials and a failed appeal and then,finally, a last appeal before the country’s highest court, which resulted in his being set free.

Cardinal George Pell, 78, archbishop of Melbourne,Australia and the Vatican’s former Prefect of the Secretariat for the Economy, on April 6, was cleared in one of the highest-profile clergy sexual abuse cases in the world when the High Court of Australia ordered his release from prison and his complete exoneration on all charges.

Pope Francis, the next day, tweeted, “Let us #PrayTogether today for all those persons who suffer due to an unjust sentence because someone had it in for them.”

And it indeed appeared that “someone had it in for” the cardinal.

Commentators on both sides of the deep divide over Australia’s Catholic Church in general agree that the cardinal’s conviction was, from the start, a miscarriage of justice. The Church is unpopular in progressive circles of Australian society,including the secular media and some sectors of government, and many believe that the police who first brought charges against the cardinal did so at the behest of others in positions of authority.

In fact, the police used unorthodox techniques in what has been described as a “fishing expedition” against the cardinal, including advertising in the newspaper for people to come forward with accusations against him — all before there were even any charges against the cardinal.

The actual charges on which the cardinal was eventually tried — twice, as the first trial resulted in a hung jury — involved two adults who, the prosecution claimed, had been sexually abused by the cardinal when they were 13-year-old choir boys at the Melbourne cathedral where the cardinal said Mass.

One of the complainants died of a drug overdose before the trial even began, but not before telling his own mother that the accusations being brought against Pell were actually not true.

The second complainant has a history of mental illness — a fact that was not allowed to enter into the cardinal’s legal defense.

Australian Justice Mark Weinberg

Canadian writer Fr. Raymond de Souza

The defense called several witnesses who all testified that circumstances surrounding the supposed crimes, which were said to have taken place immediately after a Sunday Mass, while the cardinal was still vested, and seemingly while he was still greeting parishioners leaving Mass outside the cathedral’s front doors, made the actions alleged impossible.

The court, however, concerned itself almost exclusively with judgment of the reliability of the sole living accuser’s word, and not with circumstantial or eyewitness evidence, and the jury voted to convict.

In the cardinal’s subsequent first appeal of the decision, Justice Mark Weinberg, the one dissenting judge of a three-judge Court of Appeal panel, expressed grave concern over the number of questionable elements of the case and concluded the conviction could “not be permitted to stand,” as it did not sufficiently withstand the burden of proof.

But the other two appeal judges, one of whom had no previous criminal jurisprudence experience, voted to uphold the conviction. So Pell was condemned and sent to prison while awaiting a final appeal to the highest court of Australia.

That High Court, after examining the arguments of the two judges, chose to side with Weinberg in support of Pell.

“The [Court of Appeal’s] analysis failed to engage with whether, against this body of evidence,it was reasonably possible that [the alleged victim’s] account was not correct, such that there was a reasonable doubt as to the applicant’s guilt,” the unanimous High Court wrote.

One Year Ago: Australian Cardinal George Pell arrives at the County Court in Melbourne February 27, 2019. Cardinal Pell was jailed after being found guilty of child sexual abuse; the Vatican announced his case would be investigated by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Now that Pell has been acquitted, it is unclear whether a Vatican investigation will still take place (CNS photo/Daniel Pockett, AAP images via Reuters)

Or, as Fr. Raymond de Souza explained in the National Catholic Register, “Which is to say, in plain English, that the Court of Appeal did not bother to ask whether the evidence was sufficient for conviction.‘It failed to engage the critical question: Did the mountain of evidence against the sole, uncorroborated account of the alleged victim require an acquittal on the grounds of reasonable doubt?”

As Cardinal Pell’s longtime defender, writer George Weigel, pointed out: “Pell vs. The Queen was also prosecuted in a way that raised grave doubts about the commitment of the Victoria authorities to such elementary tenets of Anglosphere criminal law as the presumption of innocence and the duty of the state to prove its case ‘beyond a reasonable doubt.’ In this regard, Justice Weinberg, the dissenting judge in last summer’s appellate case, made a crucial jurisprudential point while eviscerating his colleagues’ decision to uphold Cardinal Pell’s conviction in August 2019:By making the complainant’s credibility the crux of the matter, both the prosecution and Weinberg’s colleagues on the appellate panel rendered it impossible for any defense to be mounted.

“Under this credibility criterion, no evidence of an actual crime was required, nor was any corroboration of the charges; what counted was that the complainant seemed sincere. But this was not serious judicial reasoning according to centuries of the common law tradition. It was an exercise in sentiment, even sentimentality, and it had no business being the decisive factor in convicting aman of a vile crime and depriving him of his reputation and his freedom.”

The Vatican’s official reaction to Pell’s acquittal was measured: “The Holy See, which has always expressed confidence in the Australian judicial authority,” its Press Office said in an April 7 statement, “welcomes the High Court’s unanimous decision concerning Cardinal George Pell, acquitting him of the accusations of abuse of minors and overturning his sentence.”

“Entrusting his case to the court’s justice,” it continued, “Cardinal Pell has always maintained his innocence, and has waited for the truth to be ascertained.

“At the same time,” it underscored, “the Holy See reaffirms its commitment to preventing and pursuing all cases of abuse against minors.”

That same day, the Holy Father prayed in his daily Mass intentions “for all those persons who suffer an unjust sentence because of persecution.”

It is unclear at this time whether the Vatican’s own canonical proceedings investigating the accusations against Cardinal Pell, which were on hold pending the outcome of civil proceedings, will still go forward.

Cardinal Pell, certainly numbered among those the Pope was praying for at Mass, said in a statement that he “holds no ill will” for his accuser.

“The only basis for long term healing is truth and the only basis for justice is truth, because justice means truth for all,” he said.

“Free Even When Incarcerated”

Catholic writer George Weigel, longtime defender and friend of Cardinal Pell, on the cardinal’s “priestly character” — and whether Australia will learn from his ordeal

George Weigel

Throughout this ordeal, Cardinal George Pell has been a model of patience, and indeed a model of priestly character. Knowing that he is innocent, he was free even when incarcerated. And he put that time to good use—“an extended retreat,” as he called it—cheering his many friends throughout the world and intensifying an already-vigorous life of prayer, study, and writing. Now that he can, at last, celebrate the Mass again, I’ve no doubt that he will make, among his intentions, the conversion of his persecutors and the renewal of justice in the country he loves.

As a citizen of the Vatican, Pell did not have to abandon his work in Rome to return to Australia for trial. The thought of appealing to his diplomatic immunity never occurred to him, though. He was determined to defend his honor and that of the Australian Church, which he had led in addressing the crimes of sexual abuse (and in many other ways) for years. Pell bet on the essential fairness of his countrymen. The High Court’s decision vindicated that wager, finally. The reception of the court’s decision will tell whether the Australian media and people have learned anything from all of this.

Facebook Comments