By Lucy Gordan

Duccio Buoninsegna’s Madonna Rucellai

On June 2, 1946, Italy held a referendum to choose between remaining a monarchy or becoming a republic. This year the Government decided to commemorate this anniversary by reopening its state-owned museums after three months of lockdown. A few days before, at the reopening ceremony of Palazzo Pitti, a comment by Eike Schmidt, the Director of the Uffizi Galleries, sent shockwaves through Italy’s museum community.

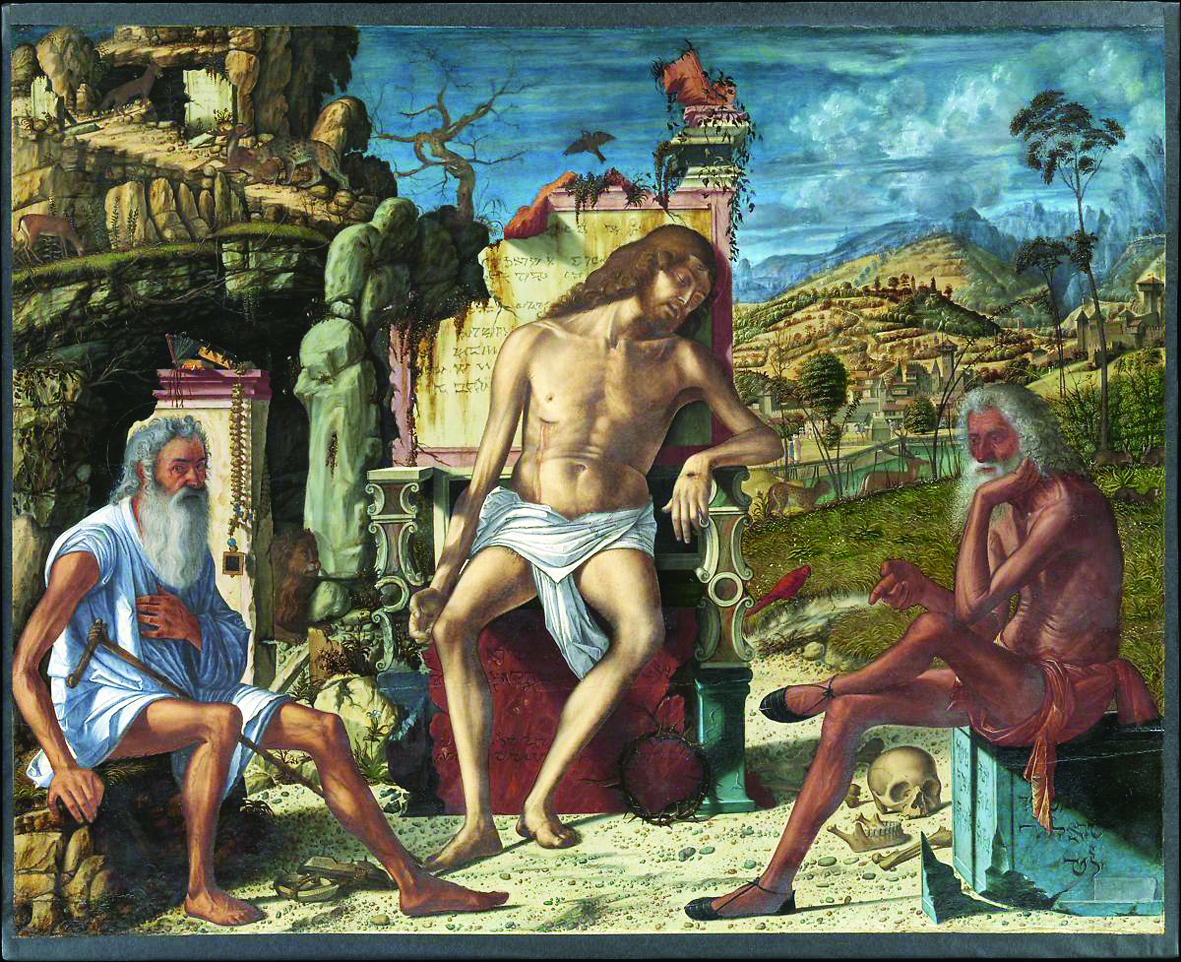

“I believe it’s time,” he said, “for state museums to perform an act of courage and return paintings to the churches for which they were originally created. Perhaps the most important example is here in the Uffizi: the Rucellai Altarpiece by Duccio di Buoninsegna, which in 1948 was removed from the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella. Since the 1950s it’s been on display with works by Giotto and Cimabue, but hasn’t ever officially become property of the Uffizi.”

“With regard to Florence,” continued Schmidt, “I’m not talking about works-of-art bought over the centuries by the Medici and the Hapsburg-Lorraine Grand Dukes of Tuscany, often for conspicuous sums, and added to their vast, ever-growing collections, but rather about altarpieces originally created for specific churches which have ended up in museum storages or which were put in museums temporarily, but have remained there without ever officially changing ownership.”

Monsignor Timothy Verdon

Professor Antonio Paolucci

Duccio di Buoninsegna (c. 1255-60-c.1318-9) is considered one of the greatest Italian painters of the Middle Ages. He received the commission for this altarpiece of the enthroned Madonna and Child flanked by six angels on April 15, 1285, from the Laudesi, a lay confraternity devoted to the Virgin. It, the largest (180 inches by 110 inches) extant 13th-century painting panel, was to decorate the confraternity’s chapel in the then-newly-built Dominican church, Santa Maria Novella. In 1591 the painting was moved to the adjacent much larger Rucellai chapel, hence the origin of its present name.

“The altarpiece’s return home,” said Schmidt, “would not only be a due act of historical justice, but also an appropriate way to celebrate, in 2021, the 800th anniversary of the Dominican Order’s investiture in Santa Maria Novella. In short, a commitment to the evermore fruitful dialog, both culturally and spiritually, between Church and State.”

“Obviously,” added Schmidt, “in order to return to their original ecclesiastical homes, these artworks’ safety from theft and vandalism, and their proper climate control has to be guaranteed first. Once resituated, these works would regain their original spiritual significance.”

Some clerics and art historians, in particular, Giuseppe Bertori, Cardinal of Florence since 2012, and polemical critic Vittorio Sgarbi applauded Schmidt’s proposal. Sgarbi even pinpointed Titian’s Annunciation and Caravaggio’s Flagellation, both in Naples’ Capodimonte Museum, saying they should both return to the Church of San Domenico in Naples.

Instead, Antonio Paolucci, Italy’s former Minister of Culture and former Director of the Vatican Museums suggested that such drastic action would deprive museums of their important didactic role and all transfers should be decided on a one-to-one basis.

Carpaccio and Caravaggio paintings which inspired Verdon’s love of art.

Schmidt’s proposal was not new — the art historian Giorgio Bonsanti proposed it during the 1990s — but many of Schmidt’s colleagues reacted indignantly. Marco Pierini, Director of Perugia’s Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria, said: “Churches are a favorite target of thieves, so it won’t be easy to protect important works of art even during opening hours. A second problem: acclimatization. Works of art long-accustomed to a controlled museum climate would have to adapt to an often humid climate and almost certainly suffer damage. A third problem: the churches’ hours: much more restricted than museums.”

The harshest criticism came from distinguished Florentine art historian Tomaso Montanari. He accused Schmidt of “conflict of interest.” In October 2019 Matteo Salvini, Minister of the Interior at the time, appointed Schmidt President of the Ministry’s FEC, Fondo Edifici di Culto, the Italian Government’s authority in charge of all church buildings and their contents. “So, Dr. Schmidt,” he asked, “FEC or the Uffizi?”

On May 29, members of Stampa Estera interviewed via Facebook Monsignor Timothy Verdon, Hoboken, New Jersey-born, but a resident of Florence for more than 50 years. He’s a distinguished art historian (Yale Ph.D. and Fellow at I Tatti, Harvard’s Center for Italian Renaissance Studies), a contributor to L’Osservatore Romano’s cultural page, Director of the Diocesan Office of Sacred Art and Church Heritage and of Florence’s Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, the first museum to reopen in Tuscany after lockdown on May 22. In addition he’s a professor at Stanford University’s Florence program and the Academic Director of the Ecumenical Center of Art and Spirituality “Mount Tabor” at Barga near Lucca.

“I believe,” Verdon said in impeccable Italian, “that Schmidt’s statement was a very positive provocation because the correct interpretation of works of art is always facilitated and enhanced by their appropriate context or location. Schmidt’s is a ‘revolutionary,’ perhaps outspoken and unpopular, proposal because it’s exactly the opposite of museum policy during the last centuries. I agree with Schmidt, but only if the designated work of art’s subject is 100% ‘religious.’ We all know that Schmidt’s proposal, if ingenious, would be almost impossible to achieve. Even if the Italian government agreed, it would have to guarantee to the Church the artworks’ safety from theft, their correct acclimatization, lighting, and installation. Such a decision implies not only the desire for historical justice, but the financial responsibility to look after their safety and conservation. I also agree with Schmidt, that it’s a question open to ‘constructive’ debate, although at this uncertain time, certainly not Italy’s most urgent cultural problem. Moreover, we experts have to be careful that, by returning artworks to their original homes, these churches don’t then become museum deposits themselves.”

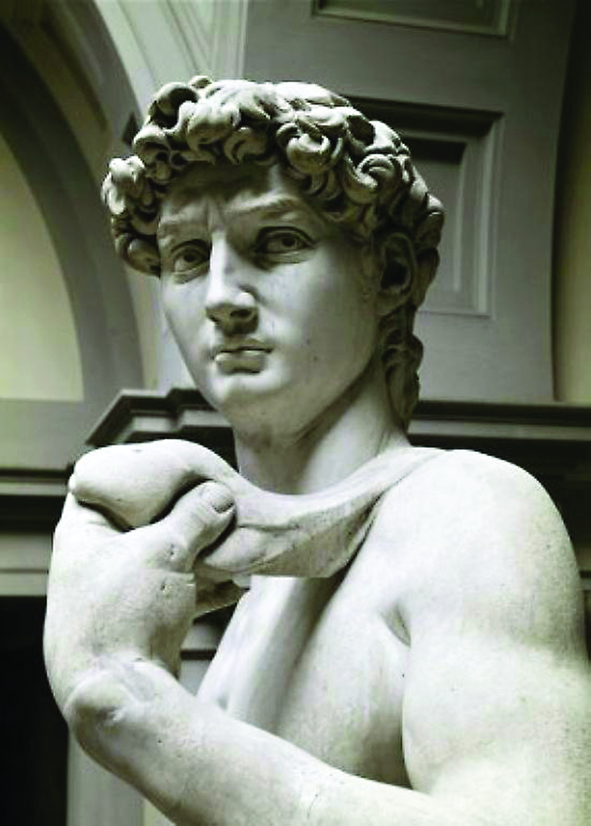

Michelangelo’s David

When asked about returning Michelangelo’s world-famous David, commissioned with other statues for the buttresses of Florence’s Cathedral, Verdon pointed out: “Although it’s a religious subject, it was never installed on the Duomo. Not to mention that, from its very beginning, so now for more than 500 years, the David has been considered more a political than religious work — considered by the Florentines as the symbol of their liberty. So to insist on returning the David to the Cathedral would be almost incomprehensible.”

Verdon’s love of art was inspired as a boy by Caravaggio’s Four Musicians and Carpaccio’s Meditation on the Passion, both in New York’s Metropolitan Museum.

Facebook Comments