“A University Training Is the Great Ordinary Means to a Great but Ordinary End”

By Stephen D. Minnis

President, Benedictine College, Atchison, Kansas, USA

St. John Henry Newman is on our minds a lot at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas. We have a Newman Residence Hall named after him, and residents from that dorm pride themselves on wearing his image on T-shirts. We also gave Newman residents what they have been requesting for many years: a chapel, named appropriately enough after St. George, the patron saint of England, St. Newman’s land.

But, more importantly, Newman is the author of The Idea of the University which has long been a guiding light for Catholic universities.

Recently, I have particularly loved one idea in The Idea of the University.

“A university training is the great ordinary means to a great but ordinary end; it aims at raising the intellectual tone of society,” Newman wrote. “It is the education which gives a man a clear conscious view of his own opinions and judgments, a truth in developing them, an eloquence in expressing them, and a force in urging them.”

That phrase about the “great but ordinary” purpose of the university hits it exactly right.

Throughout the essay, St. John Henry Newman seems to communicate this idea in several different ways. The university is not meant to make students stand out from society — it is meant to make students who deepen society.

The college magazine

This is an idea we have really taken to heart at Benedictine College. We are what we like to call the “University of Normal.” By that, I mean that we do not want to teach wild new ideas on the one hand, and we do not want to be hidebound and afraid of change on the other.

We have the same motivation Newman had for this: We want Benedictine graduates to deepen society as a whole — to make it “great but ordinary.” It is becoming clearer that what happens in college has an impact on persons and, ultimately, society, long after a student leaves.

Why do I say that? Because three things are happening to college students.

First, recent sociological studies tell us that between the ages 18-24—generally your college years—three things happen to young people: They develop life-long relationships, they make the faith their own, and they discover their vocation.

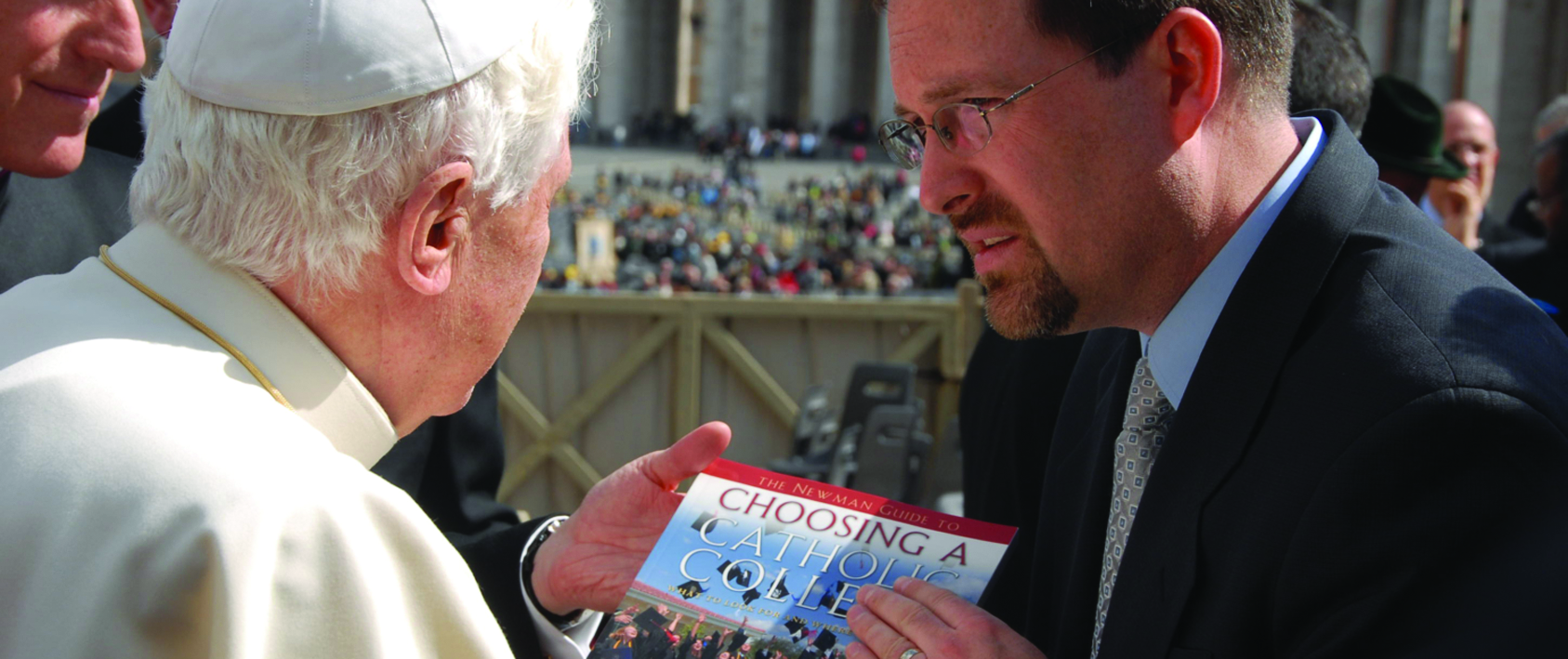

This is why, when I talk to seniors in high school, I tell them that choosing a college isn’t a four-year decision, it is a 40-year decision.

A recent Gallup-Purdue study interviewed over 30,000 people in the workforce — most of whom had been out of college and in the workforce for 10 years or more. In this study, they asked if workers were engaged in the workplace — happy and efficient in their jobs. What they found was that there were three common factors in those who were engaged in the workforce, even a decade after college: they had a professor in college who made them excited about learning; they had a mentor in college; and they had done a research project in college that sometimes took more than one semester to complete.

All three of these factors are priorities in the Benedictine education.

The Rosary is prayed by students at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas.

What’s more, Benedictine College is over 150 years old. When we were 100 years old—in the late 1950s — for every two people who received a college degree, one person retired. Basically, we were doubling the workforce. But today, for every one person who receives a college degree, two people are retiring. This generation of college students will be asked to take on leadership roles in organizations quicker than any generation in our history. So we owe it to them and to our country to prepare them for this responsibility — to help them be “great but ordinary.”

But the fact that we are a Catholic university means that we have even higher expectations for our students.

Another key passage in Newman comes when he defines the purpose for Catholic education this way: “When the Church founds a university, she is not cherishing talent, genius or knowledge for their own sake, but for the sake of her children, with a view to their spiritual welfare and their religious influence and usefulness, with the object of training them to fill their respective posts in life better and of making them more intelligent, capable, active members of society.”

Exactly right. Colleges must develop virtuous leaders — especially in America. John Adams said, “Liberty can no more exist without virtue…..than the body can live and move without a soul.”

Can you have virtue outside a faith-based community? You can, but frankly the universities in America over the past 30 years have for some reason abandoned the responsibility to develop virtuous citizens. Only a few specifically non-faith-based institutions now consider it their duty to form young people into virtuous citizens.

Therefore the country must turn to faith-based institutions, who are willing to see this as their duty, to prepare young people for virtuous leadership roles and to be virtuous citizens.

Newman stresses the need to stave off the secularist ideologies of utilitarianism and rationalism. In Benedictine College’s curriculum, we require three philosophy classes and three theology classes to teach the fundamentals of faith and reason necessary for authentic virtue. Outside the classroom, we strive to create the conditions under which virtue can exist and thrive.

Most importantly, we hire for mission. I interview every job applicant on campus, and I ask them to explain to me how they see themselves contributing to our mission — not just accept that we have a mission, but how they will support it. I want every man or woman who works for Benedictine College to be someone I hope our students will aspire to be like.

“If then a practical end must be assigned to a University course, I say it is that of training good members of society,” wrote Newman. “It teaches him to see things as they are, to go right to the point, to disentangle a skein of thought to detect what is sophistical and to discard what is irrelevant.”

Stephen Minnis has been president of his alma mater for 15 years. He received his Bachelor’s degree from Benedictine College in 1982, a JD from Washburn University, and an MBA from Baker University. Minnis practiced law as a prosecutor, in private practice and in corporate law for 20 years. He also served on the Benedictine Board of Directors for 12 years before taking on the presidency. He is married to Amy, Benedictine class of 1984 and they have three grown children: Matthew, Michael and Molly.

Facebook Comments