Il Parroco – Padre Michael McGivney e il Cattolicesimo Americano (the Paris Priest: Father Michael McGivney and American Catholicism)

Times were tough at the beginning, in the late 1800s. But soon the Knights of Columbus were growing strongly, and today they are a flourishing international association which currently counts 800,000 members in 15,000 circles throughout the United States, Canada, Central America, the Caribbean, the Philippines and, recently, in Eastern Europe. The order’s founder was Father Michael McGivney, and his biography was presented in Rome this summer. Professor Kevin Coyne from Columbia University’s School of Journalism spoke at the book launch, along with Fr. Giuseppe Costa, director of the Vatican Publishing House, which is publishing the book. Also speaking was Carl Anderson, Supreme Knight of the Knights of Columbus, and an accomplished historian in his own right.

“A decade before Rerum Novarum (published on May 15, 1891) formally launched the modern social teaching of the Church, Father McGivney was founding a lay Catholic organization that would be dedicated to both the spiritual and temporal well being of its members,” Anderson said in his remarks at the Patristic Institute Augustinianum, during the launch of the book.

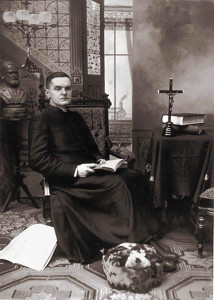

The book is the fruit of research carried out by Douglas Brinkley and Julie M. Fenster and presents the life of McGivney, a 19th-century priest from Connecticut (1852-1890; he died young at the early age of only 38) who became one of the most beloved parish priests in the entire history of the United States, as well as the founder of the Knights of Columbus, today the world’s largest Catholic confraternity.

“Father McGivney is not only a model for American priests, but for all priests as well,” Anderson said.

Right from its birth, the Knights of Columbus “would provide charity to those on the margins of society,” Anderson said. “It would be united to the Church, and would have the goal not only of evangelizing its members, but of having its members evangelize society. It would be a Catholic fraternity, drawing men together to do good. And it would show clearly to those who doubted the proposition in 19th century America, that Catholics could be excellent citizens.”

Father McGivney founded the society in 1882, helping to save numerous families from the effects of grinding poverty. At the end of the 19th century, discrimination against American Catholics was widespread. Many were completely worn out by the tough work in the factories of the day. An injury or the death of the bread-winner left families in a helpless situation. “Father McGivney’s vision had prepared the Knights of Columbus to fully embrace the reinvigoration of the role of the laity in the life of the Church by the Second Vatican Council and in the subsequent pontificates of St. John Paul II, and Popes Benedict XVI and Francis,” Anderson said. “In fact, as Supreme Knight, I have seen, over the last decade and a half, just how well Father McGivney’s vision prepared us as an organization to respond to the call of each of the great Popes who have led the Church during this period.”

McGivney “was not the kind of priest who believed his ministry ended with Sunday Mass,” Prof. Coyne said. “He organized amateur theatricals and Church picnics, featuring horse races and baseball games. (He was particularly fond of America’s national pastime; he had been a left fielder himself on his seminary baseball team.) He visited prisoners, and prayed alongside one repentant murder all the way to the gallows. When one father in his parish died too young, seemingly ending the college dreams of his talented sons, Father McGivney made sure their education continued – and both went on to Yale Law School. One of them later went on to the seminary, too, and became a priest himself.”

The Knights took their name from Christopher Columbus, “the Italian Catholic explorer who was celebrated as the discoverer of this nation even by its Protestant majority,” Coyne recalled.

Father McGivney wrote: “The object of this association is to promote the principles of unity and charity, so that the members may gain strength to bestow charity on each other.”

Coyne added: “They were a brotherhood formed as a mutual benefit society to aid members and their families in the event of illness or death, and to serve a larger mission, too – to act as a charitable force in their communities, and to support their Church, something they did so well that they were later described, as the ‘strong right arm’ of the Church in America. It started slowly. It was a new way for Catholic laymen to find a place for themselves in a new world, and it raised suspicions in some quarters – including among some priests and bishops. But it kept growing.”

Facebook Comments