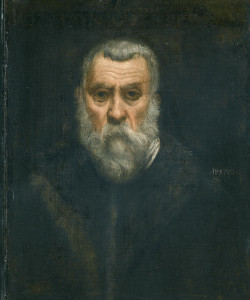

Self-portrait of Jacopo Comin, known as Tintoretto, as a young man.

If you ask even some experienced art historians about the identity and works of Jacopo Comin (September 29, 1518-May 31, 1593), they might conceivably draw a blank, yet he was one of the Venetian School’s greatest painters and probably the last great painter of the Italian Renaissance. Known as “Tintoretto,” his huge works are characterized by their liberties with traditional iconography, Michelangelo-style muscular figures, dramatic gestures, perpetual motion, energetic brushstrokes, spectacular use of perspectival space in the Mannerist style, and special lighting effects, making him a precursor of Baroque art, while maintaining the colors of the Venetian School. Due to his phenomenal, non-stop drive, this prolific artist (he painted over 600 mostly huge canvasses) was called “Il Furioso.”

In his youth he was also called Jacopo Robusti, because his father had defended the gates of Padua in a rather robust way against the imperial troops during the War of the League of Cambrai (1509-1516). Somehow his real name, “Comin,” meaning the spice cumin in Venetian dialect, was only recently discovered by Miguel Falomir, the curator of the Prado in Madrid, and made public during the only retrospective until now of Tintoretto’s work, held there in 2007.

The eldest of 21 children, this hot-tempered, ambitious, non-conformist genius, incapable of love except for his work — he closed all but one of his daughters in convents and banished all but two of his sons — was born in cosmopolitan Venice and scarcely ever traveled elsewhere. His father Giovanni was a dyer or tintore; hence the boy was nicknamed Tintoretto, little dyer or dyer’s boy, the name by which he is known.

Art Critic Vittorio Sgarbi considers Tintoretto’s Miracle of the Slave, 1542, his masterpiece.

Tintoretto was a born painter. His father, noticing his precocious gift, took him to Titian for training, but, according to legend, the great master, jealous of his student’s talent, sent him home after only 10 days and from then on gave him the cold shoulder, although Tintoretto, otherwise self-taught (most unusually for his time, he was never apprenticed to a workshop), always remained a professed and ardent admirer of his first and only “teacher,” whose contempt he ignored.

Tintoretto’s haughtiness, audacity, and willingness to work for little money so as to get commissions, however, made him unpopular in the fiercely competitive Venetian artistic community. According to his biography on Wikipedia, Tintoretto’s “noble conception of art and his high personal ambition were evidenced in the inscription which he placed over his studio: Il disegno di Michelangelo e il colorito di Tiziano (‘Michelangelo’s design and Titian’s color’).”

On now at the Quirinal’s Scuderie is “Tintoretto” — the only key Italian 16th-century painter not to have had a major monographic exhibition in post-war Italy. According to the Scuderie’s website, “If we ignore the thematic exhibition of his portraits held in Venice in 1994, the last exhibition in Italy of the great Venetian’s master work was held in 1937….” In all fairness, the reason for this “oversight” is the difficulty of transporting his enormous canvasses.

The Last Supper, 1574-5, on loan from the Church of San Polo, is one of Tintoretto’s ten canvasses of this subject.

This exhibition, like the several monographic ones which preceded it, “is part of the Scuderie’s broader program to explore those artists who have helped to make the story of art in Italy so unique and grandiose”: Botticelli, Antonello da Messina, Bellini, Caravaggio, Lorenzo Lotto, and Filippino Lippi.

“Tintoretto” is curated by the outspoken and controversial art historian Vittorio Sgarbi and “narrated” by the novelist Melania Mazzucco, who wrote a well-documented, prize-winning biographical novel of Tintoretto, La Lunga Attesa dell’Angelo (2008) (published in English as The Last Confession of Tintoretto) and a second profile of his whole family, Jacopo Tintoretto & I Suoi Figli (2009) featuring his favorite oldest daughter Marietta (1556-90), who, born out of wedlock, became a skillful portrait painter and musician.

Christ Among the Doctors 1540-1 is Tintoretto’s earliest painting on display here.

The exhibition’s 11 sections: “The Beginnings,” “The Fifties,” “The Scuole Grandi,” “Everybody’s Painter,” “The Adventurer of the School of San Rocco,” “The Painter of the Doges,” on the first floor, and “Portraits,” “Female Beauty,” “Tintoretto and ‘La Maniera,’” “The Tintoretto Company,” and “Envoi,” upstairs, are in chronological order. They begin with a youthful self-portrait on loan from London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (another hangs in the Philadelphia Museum of Art) and end with another as an old man on loan from the Louvre. His remaining 40 works here are divided into three main themes: religion (Old and New Testament stories as well as saints’ lives), portraiture, and mythology, and there is an additional small section of paintings by his contemporary artists, Titian, Il Parmigianino, Veronese, Giovanni De Mio, Lambert Sustris, Bassano, and El Greco, all working in Venice too.

The majority of Tintoretto’s opus depicts religious subjects. Several, like The Annunciation, The Washing of the Apostles’ Feet, The Last Supper, and The Deposition he painted repeatedly for different Scuole Piccole or guilds. Here on display, side by side, are two versions of his 10 Last Suppers: one, painted in 1563-1564 and on loan from the Church of San Trovaso in Venice, shows the moment when Judas’s betrayal was announced; the other, painted in 1574-1575 and on loan from the Church of San Polo, also in Venice, shows the Apostles’ Communion.

His earliest canvasses on display are Christ Among the Doctors, 1540-1541, with its telescopic perspective, on loan from the diocesan museum of Milan’s cathedral, and The Miracle of the Slave, 1542, his revolutionary very first commission for the chapter-house of Scuola Grande di San Marco, a confraternity, where Marco Espiscopi, his future father-in-law, was grand guardian, and currently housed in the Gallerie dell’Accademia. Considered Tintoretto’s masterpiece by Sgarbi, the polemics it caused certainly allowed him to grab the limelight and never again lack work. One of his many paintings depicting episodes from the life of St. Mark (not surprisingly since St. Mark is the patron saint of Venice), it portrays an event recounted in Jacopo da Varazze’s Golden Legend, showing the Saint intervening from heaven to rescue a naked slave about to be martyred for his veneration of the Saint’s relics against his master’s will. Also on loan from the Accademia are The Madonna of the Treasurers, 1567, and the masterpiece Stealing the Dead Body of St. Mark, 1564. It had been commissioned in 1562 along with two other paintings by Tintoretto’s first private patron to complete the decoration of the Scuola di San Marco. At the time Tommaso Rangone, a physician, was grand guardian of the school. He’s depicted here holding the Saint’s head.

His self-portrait as an old man.

Other of Tintoretto’s masterpieces include The Virgin Mary in Meditation and The Virgin Mary Reading, both painted for the Scuola di San Rocco between 1582 and 1584. According to Mazzucco, “In 1564 the Scuola Grande di San Rocco announced a competition to assign the painting of a picture for the ceiling in the Boardroom. The participants (Veronese, Zuccari, Giuseppe Salviati and Tintoretto) were asked to present a sketch from which the best would be chosen. Tintoretto, aware that the brotherhood was about to begin an ambitious program of decoration, wanted to secure the commission. Instead of a sketch he presented the finished painting and donated it to the Scuola, which, in accordance with its statute, could not refuse it. Thus the competition never took place. This marked the roguish beginning of one of the greatest pictorial, intellectual, religious, and human adventures in the history of Italian art,” considered by most to be Tintoretto’s masterpiece. He worked here from 1565 to 1567 and then again from 1575 to 1588.

The second theme of “Tintoretto” is portraiture. Tintoretto painted hundreds of portraits. “In his youth,” explains Mazzucco, “the subjects were mainly aristocrats, writers, and notables in Venice from whom he hoped to obtain support and publicity. From the mid 1540s the portraits ensured him a constant income with relatively little effort. Very rapidly, almost like a photographer, he would get the sketch down in a half hour sitting… For Tintoretto the subjects were simply men, and more rarely women, in whose faces he sought, by means of light, the intimate unadorned truth, beyond social class.”

Hence of the eight portraits here we know the identity of only three.

As for mythology, Mazzucco tells us: “The secular pictures — mythological ‘fables’ featuring pagan gods and goddesses — were commissioned by private individuals. Princes, prelates, aristocrats, and merchants exhibited them — and in the case of erotic subject matter sometimes concealed them — in the rooms of their palazzi… Apart from ceiling panels and frescoes on palazzo facades, mostly done in his youth, Tintoretto did not paint many secular works…” — until after Titian’s death in 1576 (for paintings of Venus were Titian’s forte) when Italian nobles and foreign royalty turned to Tintoretto for allegorical and mythological subjects. We don’t know who commissioned those on display here, but they’re all post-1576.

Tintoretto’s last painting of importance (1588) was his Paradise for the Hall of the Great Council in the Doge’s Palace (74 feet by 30 feet), reputed to be the largest painting ever done upon canvas and on February 1, 2012’s list of 20 artworks to undergo restoration sponsored by Bank of America/Merrill Lynch. Tintoretto was purported to have submitted the painted sketch, on loan here from the Louvre, as his proposal.

While awaiting their reply, Tintoretto was wont to tell the senators that he’d prayed to God that he might receive the commission, so that paradise itself might perchance be his recompense after death.

“Tintoretto” closes with the three-meter tall Deposition on loan from the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore, the last work in which it’s possible to identify the master’s hand. Begun in 1592, it was completed after his death in 1594 by his devoted, long-suffering, but less-gifted son Domenico.

Facebook Comments