Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519-1574) was the second Duke of Florence from 1537 until 1569, when he became the first Grand Duke of Tuscany. An authoritarian ruler who heavily taxed his subjects and who, like his more prominent ancestors, maintained his power by employing Swiss mercenaries, he was also an important art patron.

Between 1545 and 1553, Cosimo I commissioned the drawings, known as cartoons, for 20 tapestries, first from Pontormo, whose designs he ended up not liking, then from Bronzino, Pontormo’s best student.

The tapestries were woven in Florence in workshops especially established for the occasion under the supervision of two Flemish masters, Jan Rost and Nicholas Karcher. They recounted the story of Joseph, told in Genesis Chapters 37-50, and were hung in the Sala dei Duecento (The Hall of 200), one of the most politically important rooms in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio (“Old Palace”), still today the heart of Florentine politics. (Cosimo I took up residence here in 1540. Vasari was in charge of the apartment’s redecoration. His frescoes glorify Cosimo’s creation of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.)

In 1882, the King of Italy, Umberto I, indiscriminately brought 10 of Cosimo’s tapestries to Rome to decorate his royal palace, the Quirinal Palace, which had been the summer palace of the Popes from 1583 (during the reign of Pope Gregory XIII) until 1870. Papal conclaves were also held here in 1823, 1829, 1831, and 1846.

Since mid-February, after extensive restoration (43 restorers worked c. 120,000 hours over 27 years in the Quirinal’s restoration workshops and in the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence), all 20 tapestries have been reunited for the first time in more than 150 years. They were displayed through April 12 in the Quirinal’s Sala dei Corazzieri (“Hall of the Cuirassiers“) in an exhibition called “The Prince’s Dreams: Joseph in the Medici Tapestries by Pontormo and Bronzino.” The exhibition’s main sponsors are Gucci and the Bracco Foundation.

After Rome, the tapestries, each c. 20 feet tall but of different widths, will be on display in the Sala dei Cariatidi in Milan’s Palazzo Reale (April 29-August 23) and then will return to their original home, the Sala dei Duecento in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio from September 15 to February 15, 2016. Afterwards, those brought by King Umberto I to Rome will return to the Quirinal.

“Because of their fragility,” Professor Louis Godart, chief conservationist of the Quirinal’s works of art, said at the press preview, “it’s unlikely that all 20 tapestries will ever be displayed together again. In the future, those ten which will remain in Florence, and those ten which return here to the Quirinal, will be displayed in loco on rotation.”

It seems that Cosimo I chose the Biblical story of Joseph because he identified with its hero: a gentle and wise leader, capable of taking difficulties in stride and then of rising above them to regain his prestige. Cosimo considered Joseph his alter ego, someone who, like himself, had been able to change his fate thanks to divine intervention.

The tapestries are an example of Medici image-making, Cosimo’s conceit in likening himself to an Old Testament hero. Their episodes, some depicted vertically and some horizontally, are:

Tapestry 1 — Joseph, Jacob’s favorite son, had a first dream: Joseph, the youngest except for Benjamin, and his 11 half-brothers were gathering bundles of grain. His brothers’ bundles bowed to Joseph’s (1549, design by Bronzino, usually located Florence);

Joseph tells his eleven half-brothers of the dream he has just had: that the bundles of grain they have gathered together bowed to him; his brothers grow angry.

Tapestry 2 — Joseph had a second dream: the sun, moon, and eleven stars (representing Joseph’s brothers) bowed to Joseph. These dreams, implying Joseph’s supremacy, angered his brothers (1549, Bronzino, Florence);

Tapestry 3 — Joseph’s jealous brothers sold him into slavery to a caravan of Egyptian merchants (1549, Bronzino, Rome);

Tapestry 4 — His brothers soiled Joseph’s coat of many colors with goat’s blood and showed it to Jacob who believed him dead (1553, Pontormo, Rome);

Tapestry 5 — The Egyptian merchants sold Joseph to Potiphar, the captain of the Pharoah’s guard, who recognized Joseph’s superior intelligence and promoted him to superintendent of his household (1546-47, Pontormo, Rome);

Tapestry 6 — Potiphar’s wife tried to seduce Joseph without success. Angered by his rejection, she falsely claimed that he’d tried to rape her, using the cape he’d lost during his escape as evidence, and thus assuring his imprisonment (1549, Bronzino, Florence);

Tapestries 7 and 8 — While in prison, Joseph interpreted the dreams of his fellow-prisoners, the Pharoah’s chief baker, who he predicted correctly would be hanged, and his chief cup-bearer, who would be released. At his release Joseph asked the cup-bearer to put in a good word for him with the Pharaoh to secure Joseph’s release from prison too, but he forgot. Two years went by, but, when none of the Pharaoh’s advisors could interpret the Pharaoh’s dreams about fat and lean cows and healthy and withered corn, the chief cup-bearer suddenly remembered Joseph’s request and had him summoned. Joseph interpreted the Pharaoh’s dreams as meaning that Egypt would enjoy seven years of abundance followed by seven years of famine, and advised the pharaoh to store surplus grain. (7: 1546-7, Bronzino, Rome, and 8: the only tapestry by Salviati, 1548, Florence).

Tapestry 9 — In thanks for his wise advice the Pharaoh appointed Joseph Vizier. During the seven years of abundance Joseph ensured that the storehouses were full. Then, when famine came it was so severe that even people from surrounding nations, including Joseph’s half-brothers, came to Egypt to buy bread from the Vizier (1547, Bronzino, Florence).

Tapestry 10 — His brothers didn’t recognize Joseph, but he recognized them, accused them of being spies, and threw them in jail. When they mentioned having a younger brother Benjamin at home, Joseph released them after three days. He had their donkeys loaded with sacks full of grain, but took one half-brother Simeon hostage. He also demanded that the brothers return with Benjamin as proof they’d been telling the truth. Unbeknownst to them, Joseph also returned their money to their money sacks (1547, Bronzino, Rome).

Tapestry 11 — After they’d consumed all their Egyptian grain, the brothers persuaded their father Jacob to let them return to Egypt with Benjamin, but they were apprehensive because they didn’t know how to explain the returned money and worried about getting rearrested. When they told Joseph’s steward so, he reassured them not to worry and reunited them with Simeon. Joseph appeared as Vizier and welcomed Benjamin (1550-1553, Bronzino, Florence);

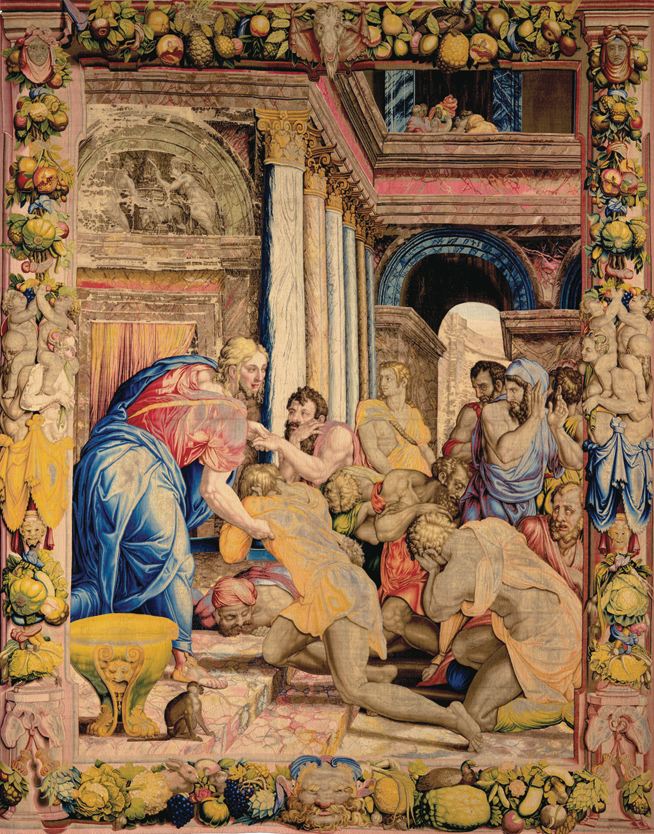

Tapestry 12 — He then hosted a banquet for his brothers who, except for Benjamin, who kept silent, still hadn’t recognized him. The Egyptians would not dine with Hebrews at the same table, as doing so was considered loathsome, so all the brothers were served at a separate table (1550-53, Bronzino, Rome);

Tapestry 13 —That same night Joseph ordered his steward to load the brothers’ donkeys with food and all their money. Deceptively Joseph ordered that his silver cup be put in Benjamin’s sack. The following morning, the brothers including Benjamin began their journey home. Joseph sent his steward after them. Of course, the steward found the cup in Benjamin’s sack just as he had planted it the night before (1550-1553, Bronzino, Rome).

Joseph offers a banquet to his brothers and, that same night, orders his steward to load the brothers’ donkeys with food and all their money

Tapestry 14 —The steward escorted them back to the Vizier, who feigned anger for the “theft” and demanded that Benjamin become his slave (1546-47, Bronzino, Rome), but…

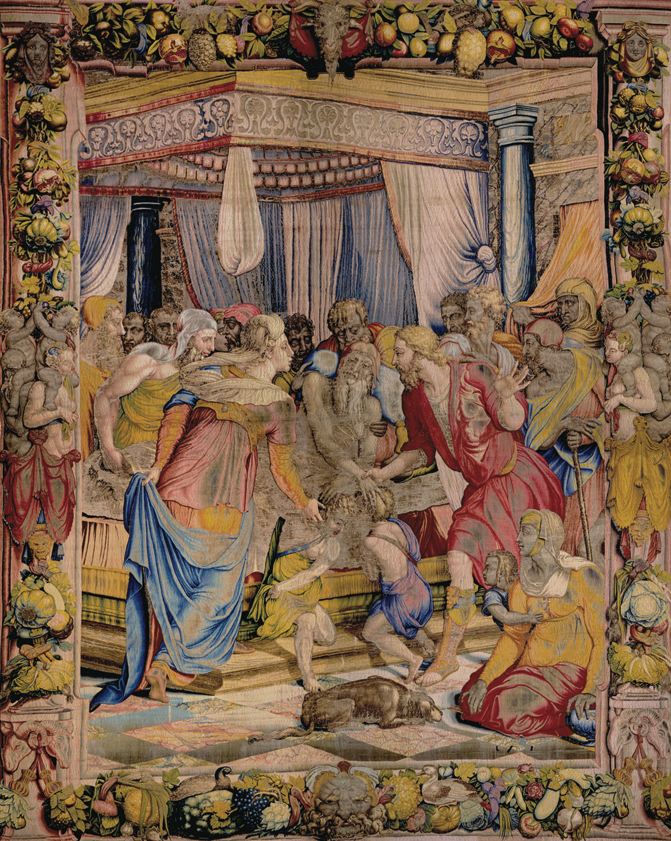

Tapestry 15 — then revealed his true identity (1550-53, Bronzino, Florence);

Tapestry 16 — Joseph pardoned his brothers, but commanded them to bring their father and his entire household to Egypt to live in the province of Goshen, because there were still five more years of famine left (1550-53, Bronzino, Florence);

Joseph pardoned his brothers, but commanded them to bring their father and his entire household to Egypt.

Tapestry 17 — It had been over 20 years since Joseph had last seen his father. When they met in Goshen, they embraced and wept. Jacob remarked, “Now let me die, since I have seen your face, because you are still alive” (1550-53, Bronzino, Florence);

Tapestry 18 — Because of his high esteem of Joseph, the Pharaoh met and accepted Jacob and his family (1553, Bronzino, Rome);

Tapestry 19 — Jacob and his family lived happily in Egypt for many years. Then Jacob fell ill and lost most of his vision. He was 147 years old and bedridden, so he summoned Joseph to his home and pleaded with him not to bury him in Egypt, but in Canaan with his forefathers. Joseph agreed. Later he brought his sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, to be blessed by Jacob, who gave Joseph and his sons a large piece of his property in Canaan (1550-53, Bronzino, Florence);

Jacob blesses Ephraim and Manasseh, Joseph’s children, and gives them

a large piece of his property in Canaan

Tapestry 20) Jacob’s burial in Canaan (1553, Bronzino, Rome).

Professor Godart, with a smile, likened the tapestries to a Renaissance comic strip, and said that in his opinion the two stars were: No. 6, Joseph’s flight from Potiphar’s wife because of the motion of their figures, and No. 12, the banquet scene because of its perspective and details.

As can be seen from the story’s summary above, the tapestries weren’t executed in their narrative sequence, although they’re displayed so in “The Prince of Dreams.” The tapestry of Joseph in Prison and the Pharaoh’s Banquet, which was delivered in 1546, served as a prototype for the whole series.

Facebook Comments