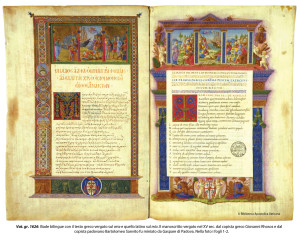

Although Pope Nicholas V (1447-55), the first learned Renaissance humanist Pope, established the Vatican Library in 1448 by combining some 350 Greek, Latin, and Hebrew codices inherited from his predecessors with his own book collection and extensive acquisitions, among them manuscripts from the Imperial Library of Constantinople, he did not live to see the design of his project — governance through culture — finished. The Library wasn’t formally established until the papal bull of Sixtus IV (1471-1481) dated June 15, 1475, today one of the Library’s innumerable treasures. The bull appointed as librarian Bartolomeo Platina, born Sacchi (1421-1481), former soldier, author of the first printed cookbook, De honesta voluptate e valetudine (On honorable pleasure and health) (written c. 1465, its manuscript is also in the Vatican Library; printed 1475), and biographer of the Popes (Vite dei romani pontefici (1479). Melozzo da Forlì immortalized this event in a fresco, now in the Vatican Museums, which depicts Platina kneeling before a seated Pope Sixtus IV and his two cardinal nephews, Rafaelle Riario and Giulio della Rovere, standing nearby.

In 1481, Platina produced its first inventory of 3,500 items, making the Vatican Apostolic Library by far the largest public library in the Western world, in accordance with Nicholas V’s wish to make its contents, constantly increased thanks to its scriptorium, accessible to scholars.

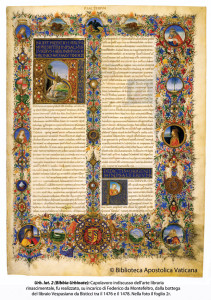

These two Renaissance Popes, as well as Nicholas V’s immediate successors, Calixtus III (1455-58), Pius II (1458-64), and Paul II (1464-71), and later art patrons Julius II (1503-1513) and Leo X Medici (1513-21), Paul III (1534-49), and Paul IV (1555-59), who added a printing press, all understood that the papacy could no longer maintain itself as a major military or political power, but that, as patrons of art, architecture, music, science, and scholarship, they could regain much of the authority that they were losing on the battlefield. That’s why they hired artists to restore Rome, reduced during the Middle Ages to a swampy wasteland, to its former cultural and architectural greatness of Classical times, transforming the city into a worthy pilgrimage site for Christians.

In this way, the early modern papacy became the first Western government to make the systematic use of intellectual and cultural tools a central component of its policy and budget; in other words, it was responsible for the introduction of the politics of culture. It was the first knowledge-based government, and no institution reflects these efforts more vividly than the Vatican Library.

The Vatican Library is not a library of religious books, as one might easily assume. Of all the Renaissance manuscripts, only about 5% have to do with religion. It’s primarily a library of humanistic research with strengths in mathematics and the sciences.

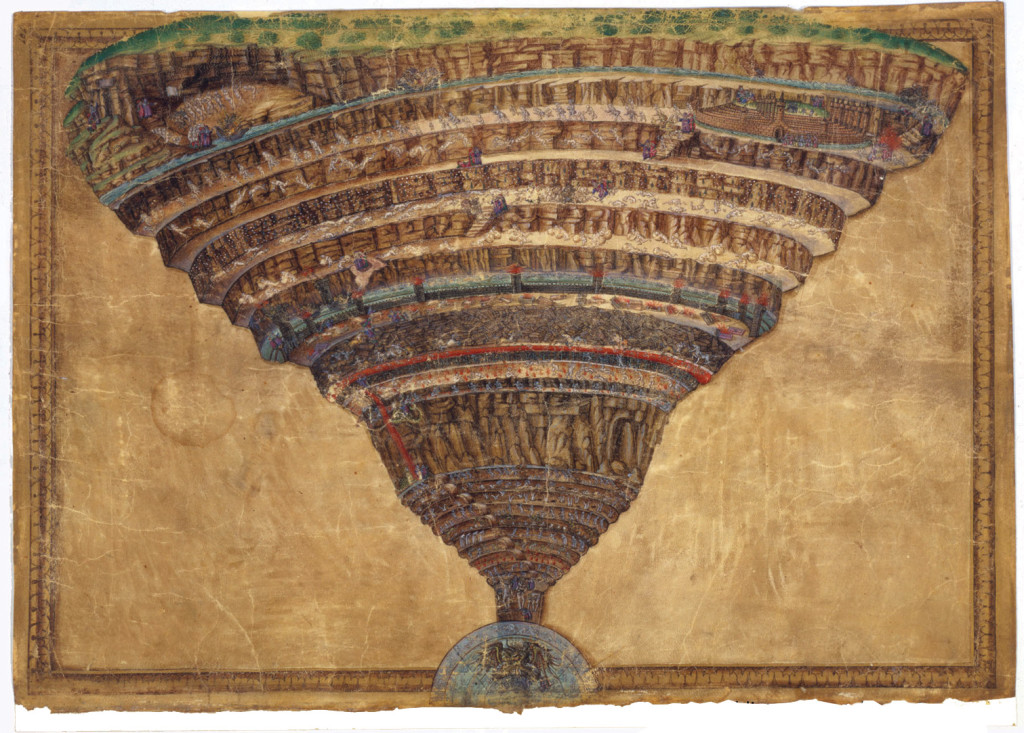

“The Library’s founders, Popes and scholars alike,” wrote Anthony Grafton, chief curator in the introduction to “Rome Reborn: The Vatican Library and Renaissance Culture,” the catalogue of a splendid exhibition held in 1993 at the Library of Congress of 196 treasures from the Vatican Library, “hoped they could renew education, literature and philosophy, and theology, not by looking at an uncertain future but by turning backwards to a perfect past.

“Convinced that they could find the best models for literature, the soundest philosophy, the most accurate history and the best guidance for conduct in the accumulated wisdom of the Greeks and Romans, the Bible, and the writings of the

Fathers of the Church, they turned to books for the knowledge that they considered most worthy of having.”

However, since the books they needed most tended to be scarce or inaccessible, papal support scholars fanned out all over Europe, ransacking private and institutional libraries and searching in monasteries for rare texts that had been copied in antiquity and the early Middle Ages, but had fallen out of fashion. In his best-selling The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, Harvard Professor Stephen Greenblatt recounts how the humanist Poggio Bracciolini discovered in a German monastic library the last surviving manuscript (today in the Vatican Library) of the ancient Roman philosophical epic, On the Nature of Things by Lucretius.

The 1613 manuscript of an oath taken by 42 Japanese Christians to defend their missions

on pain of death.

What the book hunters could not copy in situ, they stole and brought back to Rome, where they translated into Latin the works of Greek poets, philosophers, scientists, and historians, many of which had been unknown in the West since ancient times.

Today many people are aware of the Popes’ role as literary patrons, as archeologists, discovers of classical texts, and as patrons of the visual arts and music, but few realize their tremendous contribution to science, medicine, and geography and how much the Scientific Revolution owed to the rediscovered science of ancient Greece.

In keeping with Pope Nicholas V’s mandate to make the Library’s contents available to his contemporary scholars and his humanistic successors’ conviction to bring Renaissance Rome into the modern world by sourcing the past, on March 20 the Vatican Library embarked on a new milestone. It signed an agreement with the Japanese NTT Data Corporation to digitalize and put online as high-definition image data with a secure back-up system 3,000 Vatican manuscripts totaling 1.5 million pages, over the next four years. NTT DATA Corporation will supply for now 20 technicians and state-of the-art equipment, which will include 5 scanners working in two daily shifts. To defray the project’s estimated $23 million cost, the Library will solicit donations, among other ways by allowing contributors to sponsor the digitalization of individual manuscripts. Moreover, in addition to its access benefits, it shouldn’t be forgotten that digitalization is the best form of manuscript conservation.

For the past several years the Library had been scanning its collection intermittently with the help of various non-profit groups, and has already archived about 6,800 manuscripts, Msgr. Cesare Pasini, the Library’s Prefect, reported. But only some 300 documents are accessible on its website (www.vaticanlibrary.va).

If all goes smoothly, the Library plans to offer a total of 15,000 manuscripts online, free of charge to all “visitors,” by 2018 and ultimately its entire 82,000 manuscripts for a total of 41 million pages.

Msgr. Pasini declined to estimate how long it would take to complete the project, although it should go faster and better as technical expertise improves.

The first manuscripts to digitalize were chosen for their importance in the overall collection, secondly for their importance to Japan, thirdly by their difficulty for the scanners to manipulate and fourthly for their rarity in the Library’s Far Eastern holdings.

For the papacy’s thirst for knowledge about cultures that had not historically belonged to Western Christendom is relatively little known.

Of course its efforts were not disinterested, but were a part of its missionary zeal to convert the infidels of the newly-discovered Americas and of Asia. Among the Library’s holdings in this regard are diaries kept by missionaries, in particularly Jesuits in China and Japan (considered the hardship post because of Japanese xenophobia), polyglot Bibles and Gospels in many tongues, and maps.

For the Orient, the Jesuits had written long tracts on Christianity, compiled dictionaries of Western languages and translated manuscripts of new Western scientific discoveries, but they also learned and brought home to the West immense amounts of knowledge about astronomy and cartography and vast runs of non-Western manuscripts and block printed books.

According to its website, in addition its 82,000 manuscripts the Library preserves 1,600,000 printed books, over 8,600 incunabula, over 300,000 coins and medals, 150,000 prints, drawings, and engravings, and over 150,000 photographs.

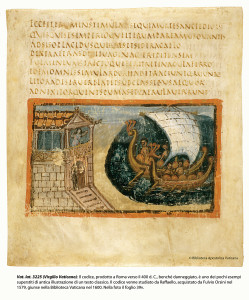

Among its oldest treasures are a 3rd-century small square-shaped papyrus codex, in excellent state of conservation, the oldest manuscript of St. Peter’s letters; a 4th-century Greek Bible known as the “Codex Vaticanus,” “Codex B” conserving almost the entire Greek text of the Bible, and four 4th-century manuscripts of Virgil’s poetry, one of which includes 50 miniatures.

Facebook Comments