Cardinal André Vingt-Trois, Archbishop of Paris and President of the French Bishops’ Conference.

One of the world’s most secularized societies is that of France. And yet, this year an unlikely coalition in defense of traditional marriage has emerged from within that society, led by the cardinal archbishop of Paris and president of the French bishops’ conference, André Vingt-Trois. Because of this almost miraculous development, we are honoring Vingt-Trois as one of the “Top Ten” people of 2012.

France’s new president, the Socialist Party leader François Hollande, during the 2012 presidential campaign, promised to “reform” France’s family law by making it legal for homosexual couples to marry and, especially, to adopt children. He also promised the legalization of euthanasia — the “mercy killing” of aged and infirm people. Both of these proposals are seen as harmful to human dignity by the Church’s moral teaching.

But how is one to explain that harm to the members of a society so secularized that they no longer see the harm, but rather something to be made legal? That has been the great problem facing Vingt-Trois and other Catholic leaders around the world.

Vingt-Trois decided to build a coalition.

And he decided to base his arguments on a point on which people of many faiths, or of none, might agree: the good of children.

Patiently, reaching out to all of French society, Vingt-Trois began to argue his case. In late summer, he wrote a special prayer called A Prayer for France, and sent it to all the dioceses to be read on August 15, the Feast of the Assumption. The national prayer for France is a very old custom. In 1638, King Louis XIII decreed that churches should pray for “the good of the country” on August 15 to mark the Feast of the Assumption. The annual practice fell into disuse after the Second World War, but Vingt-Trois decided to revive it.

In his prayer, Vingt-Trois asked churchgoers to pray for France’s “newly-elected leaders” to put their “sense of common good over the pressure to meet particular demands.” This was a key point, as he argued also on another occasion: that the legislation “is not for all citizens, but only for a few.”

Something extraordinary happened. Since the summer, French religious leaders, most of them Catholic, but also a number of Jews, Muslims, Protestants and Orthodox, as well as conservative politicians of no particular religious faith, have begun to mobilize against the proposed law, especially against the provision allowing homosexual couples to adopt children.

The campaign found a way to use against the law the very logic and arguments of the proponents of the law. Proponents of the law argued that it was a matter of “civil rights” — of “human rights” — to allow homosexuals the same rights to marriage and parenthood as heterosexuals. But the opponents of the law began to argue that, yes, it was a matter of “civil rights,” of “human rights,” but not of the civil rights of the parents, but of the children. Children have rights, too, and among those rights is the right to have a mother and a father, not just a father and a father or a mother and a mother. Passing a bill legalizing same-sex marriage and allowing homosexual couples to adopt children would not be in the best interest of children, and would, in fact, “discriminate” against children, as well as “shake the foundations of our society,” Vingt-Trois argued at the autumn plenary meeting of French prelates at Lourdes.

The campaign then began to argue that the consequence of the new law was not merely to grant a denied “right” to a class of people who desired that right, but to shake the entire social structure, and so to affect everyone. “Far from simply opening marriage to new categories, the bill on same-sex marriage would involve such changes as would affect everyone,” Vingt-Trois said. “Such radical transformations require a national debate, and not simply unreliable opinion polls or the strong pressure of some lobbies.”

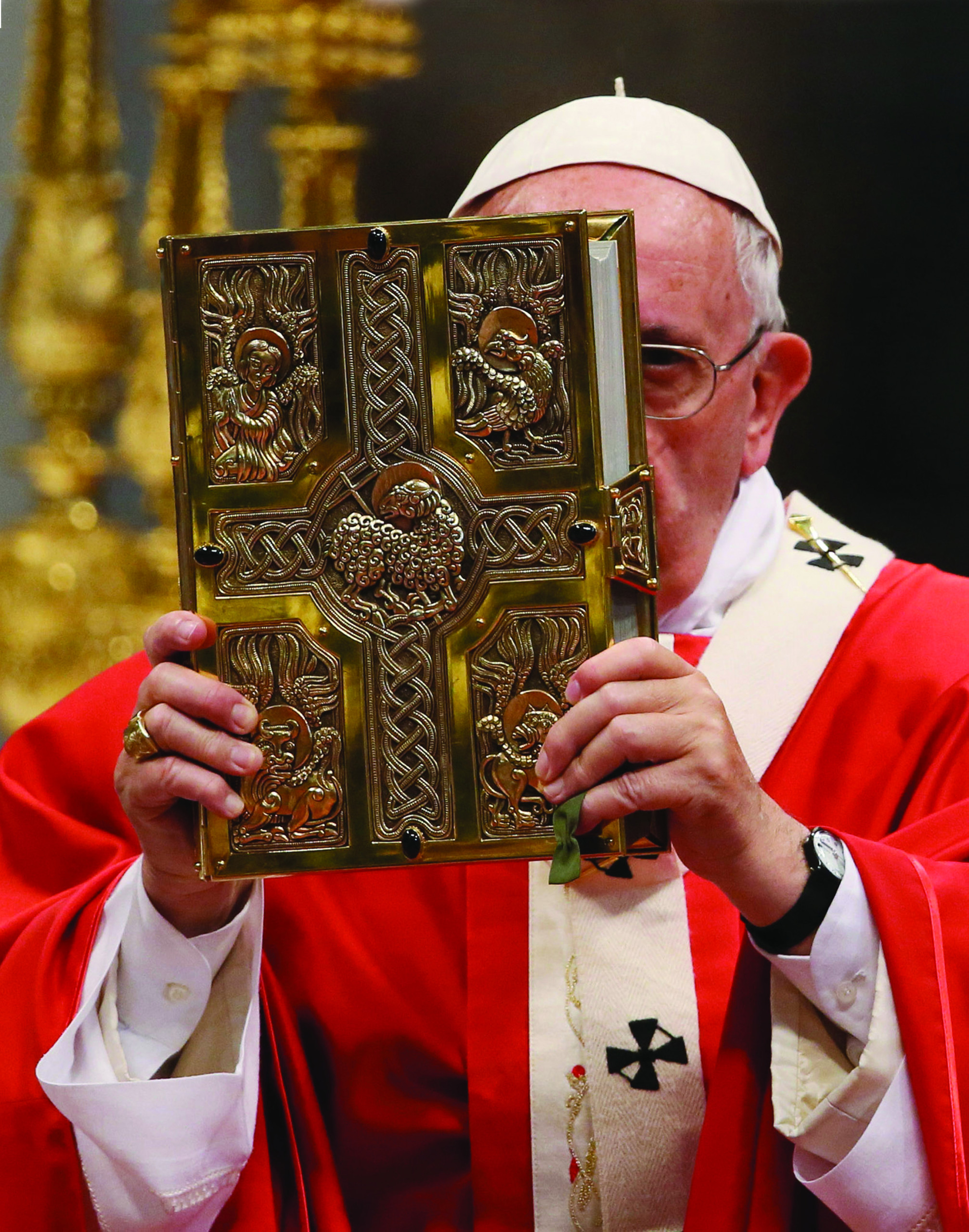

Cardinal Vingt-Trois greets the faithful in Paris.

Vingt-Trois then developed a third argument: that the government was focusing on this marriage and parenthood legislation in order to avoid dealing with the tough economic problems of the country which were affecting every citizen’s quality of life. “We regret that the government’s choice focuses public attention so much on an issue that’s actually secondary,” he said. “The priority concerns plaguing our fellow citizens are the consequences of the economic and financial crisis — closing factories, rising unemployment, growing uncertainty for the poorest families.” Vingt-Trois urged Catholics to show their opposition to the planned reform by writing to their representatives and taking part in protest marches.

On November 19, Vingt-Trois held a press conference at the Saint Louis de France Centre in Rome. Demonstrations against the law on the previous weekend had drawn “more people than expected,” he said. Why? Because many Catholics have begun to see the need for “public witness,” but also because “believers of other religions or agnostics, people of every political orientation” have begun to have “substantial questions about the reform.”

For his courageous witness to Catholic moral principles, and for his staunch defense of the rights of children, we are pleased to honor Cardinal Vingt-Trois as one of our “Top Ten” of 2012.

Facebook Comments