(From www.chiesa.espressonline.it Rome, November 30, 2009)

Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio meets Argentine President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner at the Casa Rosada (The Pink House) in 2007.

Two days ago, Benedict XVI received the president of Argentina, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, and of Chile, Michelle Bachelet, who arrived with their respective delegations to thank the Holy See for the peaceful solution arranged twenty-five years ago by Vatican diplomacy to the territorial dispute between the two countries about sovereignty over the islands south of the Beagle Channel.

Argentina and Chile, together with Colombia, are the nations in South America in which the Catholic Church is most firmly planted.

But they are also the ones in which the challenge of secularization is most relentless: in mentality, in customs, and in legal norms. On November 13, a judge in Buenos Aires authorized a “marriage” between persons of the same sex, declaring the articles of the civil code outlawing it unconstitutional. The chief of government of Buenos Aires has taken the side of the judge. And this has provoked a vigorous reaction from the archbishop of the city, Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, who is also president of the Argentine bishops’ conference, a person much loved and respected.

The Church’s response to the challenge of secularization is a decisive test for verifying the success or failure of the pastoral guidelines elaborated for the subcontinent by the meeting of Latin American bishops’ conferences held in 2007 in Aparecida.

Secularization, in fact, erodes what is a typical characteristic of the Catholic Church in these countries: that of being a Church of the people, with the family as the foundational structure and with the baptism of children as a general practice.

In some parts of Europe, baptizing a child has already become the exception, requiring an unconventional decision. But now, the number of unbaptized infants, children, young people, and adults is also rising in Argentina.

This decline in the practice of baptism is the result of a weakening of family ties and a withdrawal from the Church. Some of the clergy have drawn this conclusion: where they see the signs of faith being extinguished, they maintain that it is right to decline to administer the sacraments.

But in Argentina today, the Church authorities are moving in the opposite direction.

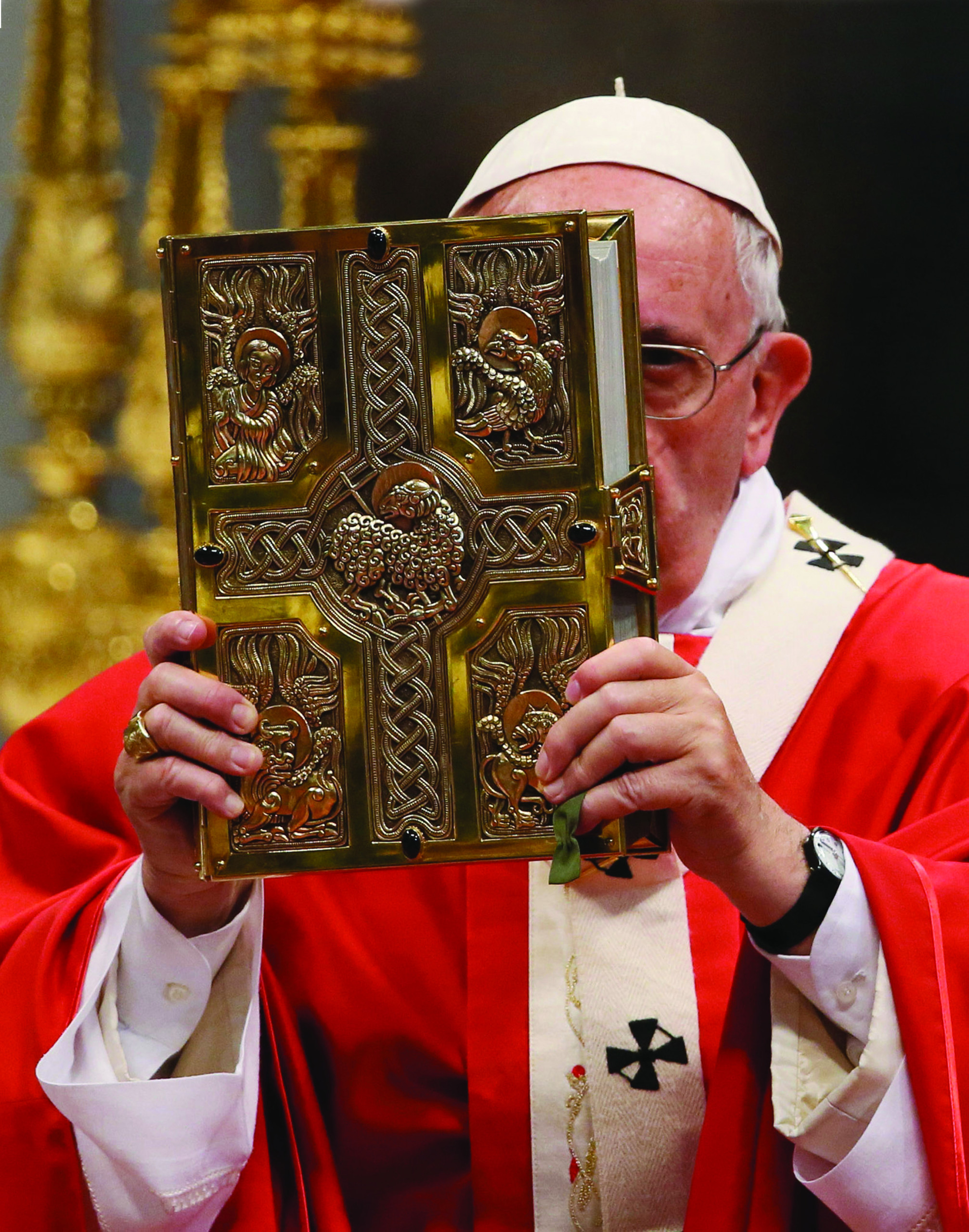

Pope Francis, then-Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, pictured in a 2009 photo.

Already in 2002, the archdiocese of Buenos Aires and the dioceses in the surrounding area had published an instruction urgently recommending the baptism of both children and adults, and explaining how to overcome resistance to the celebration of the rite.

But now the bishops of the area have returned to the task with a booklet entitled El bautismo en clave misionera, which reproduces the 2002 instruction and supplements it with other guidelines for parish pastors.

So beginning this year, the most conscientious pastors are regularly holding “baptism days,” on which they administer the sacrament to children and adults in situations of poverty or with broken families, who have been helped to overcome their own uncertainties and those of the people around them.

Cardinal Bergoglio has explained the meaning of all this in an interview with the international magazine 30 Days:

“The child has no responsibility for the condition of his parents’ marriage. The baptism of children can, on the contrary, become a new beginning for the parents. A while ago, I baptized the seven children of one woman, a poor widow who works as a maid and had her children by two different men. I met her on the feast of Saint Cajetan. She said to me, ‘Father, I am in mortal sin, I have seven children and have never had them baptized, I don’t have the money for the godparents and for the party…’ I saw her again and after a little catechesis I baptized them in the chapel of the archepiscopal residence. The woman said to me, ‘Father, I can’t believe it, you make me feel important’. I said to her, ‘But madam, what do I have to do with it? It’s Jesus who makes you important.’”

Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio celebrates Mass in honor of Pope John Paul II at the Buenos Aires cathedral April 4, 2005. At the time, Vatican watchers had named Cardinal Bergoglio as a possible candidate to succeed Pope John Paul II (CNS photos).

Bergoglio is anxious not to extinguish a tradition typical of the most remote areas of Argentina, in those towns and villages where the priest comes only a few times a year:

“There, popular piety feels that children must be baptized as soon as possible, so there are men or women known by all as ‘bautizadores’ who baptize the children when they are born, in anticipation of the arrival of the priest. And when he arrives, they bring the children to him so that he can anoint them with holy oil, completing the rite. When I think about it, I am reminded of the story of those Christian communities in Japan that were without priests for more than two hundred years. When the missionaries returned, they found all of them baptized and all of them sacramentally married.”

The cardinal continues:

“The conference in Aparecida urged us to proclaim the Gospel by going to meet the people, not by waiting for the people to come to us. Missionary fervor does not require extraordinary events. It is in ordinary life that mission work is done. And baptism, in this, is paradigmatic. The sacraments are for the life of men and women as they are. They may not make big speeches, but their sensus fidei grasps the reality of the sacraments with more clarity than many specialists do.”

What reemerges here is the ancient and still unresolved dispute between a Church of the elite, a pure, minority Church, and a Church of the masses, populated also by that immense sea of humanity for whom Christianity is made up of a few simple things.

In Italy, for example, the dispute came up again during the last major national conference of the Church, held in Verona in October of 2006. On that occasion, one position held by the “rigorists” was precisely that of withholding baptism and the other sacraments from those believed to be unfit because they are not practicing.

It is a dilemma that Joseph Ratzinger himself experienced personally as a young man, and finally resolved in the same direction indicated by Cardinal Bergoglio. This is what, as pope, Ratzinger himself said in replying to the question from a priest of Bressanone, in a public question-and-answer session with the clergy of the diocese on August 6, 2008.

The priest, named Paolo Rizzi, a pastor and professor of theology, asked Benedict XVI a question about baptism, confirmation, and First Communion:

“Holy Father, 35 years ago I thought that we were beginning to be a little flock, a minority community, more or less everywhere in Europe; that we should therefore administer the sacraments only to those who are truly committed to Christian life. Then, partly because of the style of John Paul II’s pontificate, I thought things through again. If it is possible to make predictions for the future, what do you think? What pastoral approaches can you suggest to us?”

Pope Ratzinger responded:

Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio meets Pope Benedict XVI during a general audience in

St. Peter’s Square on October 12, 2005 (Galazka photo)

“I must say that I took a similar route to yours. When I was younger I was rather severe. I said: the sacraments are sacraments of faith, and where faith does not exist, where the practice of faith does not exist, the sacrament cannot be conferred either. And then I always used to talk to my parish priest when I was archbishop of Munich: here too there were two factions, one severe and one broad-minded. Then I too, with time, came to realize that we must follow, rather, the example of the Lord, who was very open even with people on the margins of Israel of that time. He was a Lord of mercy, too open — according to many official authorities — with sinners, welcoming them or letting them invite him to their dinners, drawing them to him in his communion.

“Therefore I would say substantially that the sacraments are naturally sacraments of faith: when there is no element of faith, when First Communion is no more than a great lunch with beautiful clothes and beautiful gifts, it can no longer be a sacrament of faith. Yet, on the other hand, if we can still see a little flame of desire for communion in the faith, a desire even in these children who want to enter into communion with Jesus, it seems to me that it is right to be rather broad-minded.

“Naturally, of course, one purpose of our catechesis must be to make children understand that Communion, First Communion, is not a ‘fixed’ event, but requires a continuity of friendship with Jesus, a journey with Jesus. I know that children often have the intention and desire to go to Sunday Mass but their parents do not make this desire possible. If we see that children want it, that they have the desire to go, this seems to me almost a sacrament of desire, the ‘will’ to participate in Sunday Mass. In this sense, we naturally must do our best in the context of preparation for the sacraments to reach the parents as well, and thus to — let us say — awaken in them too a sensitivity to the process in which their child is involved. They should help their children to follow their own desire to enter into friendship with Jesus, which is a form of life, of the future. If parents want their children to be able to make their First Communion, this somewhat social desire must be extended into a religious one, to make a journey with Jesus possible.

“I would say, therefore, that in the context of the catechesis of children, that work with parents is very important. And this is precisely one of the opportunities to meet with parents, making the life of faith also present to the adults, because, it seems to me, they themselves can relearn the faith from the children and understand that this great solemnity is only meaningful, true and authentic if it is celebrated in the context of a journey with Jesus, in the context of a life of faith. Thus, one should endeavor to convince parents, through their children, of the need for a preparatory journey that is expressed in participation in the mysteries and that begins to make these mysteries loved.

“I would say that this is definitely an inadequate answer, but the pedagogy of faith is always a journey and we must accept today’s situations. Yet, we must also open them more to each person, so that the result is not only an external memory of things that endures but that their hearts have truly been touched. The moment when we are convinced the heart is touched — it has felt a little of Jesus’ love, it has felt a little the desire to move along these lines and in this direction, that is the moment when, it seems to me, we can say that we have made a true catechesis. The proper meaning of catechesis, in fact, must be this: to bring the flame of Jesus’ love, even if it is a small one, to the hearts of children, and through the children to their parents, thus reopening the places of faith of our time.”

Facebook Comments