On October 2, 2014, at an international conference organized by the Guglielmo Marconi University in Rome, scholars from around the world gathered to further explore the pontificate of Pope Pius XII. Entitled “Pius XII and the Second World War: Events, News, and Hypotheses from the Archives,” the conference was convened in anticipation of the opening of the Vatican Secret Archives and the Archives of Relations with States from the World War II era, which are expected to shed additional light on the role of Pope Pius XII and the Catholic Church during World War II.

Eduardo Husson.

Although these proceedings were open, they were in some way a continuation of a closed discussion held two years earlier at the Sorbonne in Paris, France. That debate was limited to scholars; there were no journalists and no publications of the proceedings. As such, there was little reporting on that event. Now, however, Eduardo Husson, the former vice-chancellor of the Sorbonne and convener of the Paris meeting, made introductory remarks in Rome.

Husson explained that the Paris discussion involved historians who both supported and opposed Pius XII, but they engaged in respectful debate and reached some undeniable conclusions. “The more you work on the Nazi dictatorship, the more you understand the opposition between it and the Pope,” he said. “Nazi leaders hated everything there is to do with the Vatican and the papacy of Pius XII.”

After two days of discussion in Paris, there was no resolution, but progress was made. The Pro-Pius historians were able to show with documents that Pius was able to do much to protect and save Jewish victims. The anti-Pius scholars had a harder time.

Husson set forth several points for agreement from the meeting at the Sorbonne, including:

1. The theatrical play The Deputy is non-historical and should no longer be cited as a factual source in the debate over Pope Pius XII.

2. Pius was not blindly pro-German.

3. The precise relationship between Pius XI and Cardinal Pacelli, as they formed a spiritual resistance to the dictatorships in the late 1930s, is still unclear.

4. Few contemporary people understood what was going on or about to take place during the war.

5. Zionism played a role that still needs study.

6. Catholics had a very negative view of the dictators.

7. Popes Pius XI and Pius XII were strongly anti-communist.

8. Pope Pius XII played a significant role in transforming the Church’s attitude toward Jews. The common perception is that Vatican II changed everything, but Pius XII had a very positive (though often overlooked) impact on Catholic-Jewish relations.

Husson also set forth the following findings from the Sorbonne conference:

1. Younger scholars and newer scholarship seems to be moving in favor of Pius XII.

2. Documents are being brought back into debate. (Husson did not mention him by name, but he referred to a comment made by a critic of Pius XII at the event in Paris, which disparaged the use of documentary evidence.)

3. We are returning to a classical debate about the ability of one person to influence events versus contextualization.

4. Focusing on the actual history is the only way to find the truth and avoid the confusion created by The Deputy.

5. With a more accurate view of Pius XII’s actions, it is easier to understand him.

The proceedings in Rome developed some of these ideas and brought forth further points for consideration, but they did nothing to undercut the overwhelmingly positive consensus that has developed regarding Pius XII’s leadership of the Catholic Church during World War II.

Matteo Luigi Napolitano of the Università degli Studi “G. Marconi” di Roma was the convener of the Roman meeting. He noted that the day is approaching when the Vatican archives will be made public in their entirety. At that time, the veil will slip away, revealing the truth and the self-serving and ideological nature of much controversy over Pius XII. Among other things, scholars will see that the Holy See’s diplomatic activity extended well beyond the actions of Pius XII and included a series of initiatives and services by groups that today we know little or nothing about.

As for Pius himself, Napolitano flatly stated that the archives have disproved the “black legend” of Pope Pius XII as someone who collaborated with the Nazis or lacked compassion for the Jews. That false caricature has been “totally wiped out by documents found in archives of other governments and by the work of scholars who have done good historical work.”

Andrea Riccardi.

Andrea Riccardi, of the Università degli Studi di Roma Tre, spoke on The Italian Church, Dioceses and Catholic Clergy in the Second World War. His focus was on the importance of papal diplomacy. Pius XII stood at the crossroads of 20th century Catholicism, and he was very deliberate when making decisions. This led to some dissent in the Church. For instance, some Polish Catholics (mainly those in London) wanted more dramatic political gestures. Internal Vatican politics also led to some criticism from within. Prof. Riccardi explained, however, that the dissent was limited and appropriate. It is a mistake to look at occasional remarks and suggest that there was significant disagreement over the Pope’s approach. Roman people remember that he protected Rome and saved many Jews.

Pius XII was the very model of a bishop who would not leave his people. His Christmas 1943 statement, which is often overlooked, was very important. In it he spoke of “stray people.” This was a code that told priests that they have to protect everyone, Catholic or not. Similarly, signs were put up on Church property, essentially inviting people in to hide from Nazis. Because these actions were somewhat disguised, the Nazis missed them (or at least let them slide). Unfortunately, so have many historians. Pius XII was a beacon of Rome, the defender of the city. Because of his actions, the 1933 concordat with Germany was used to protect Jews and to smuggle aid to those under Nazi persecution. In fact, Prof. Riccardi said that we should not speak of the liberation of Rome but of the rescue of Rome (by Our Lady, to whom Pius XII was so devoted). Historians should look at the many individual acts, without overlooking the influence of the Pope.

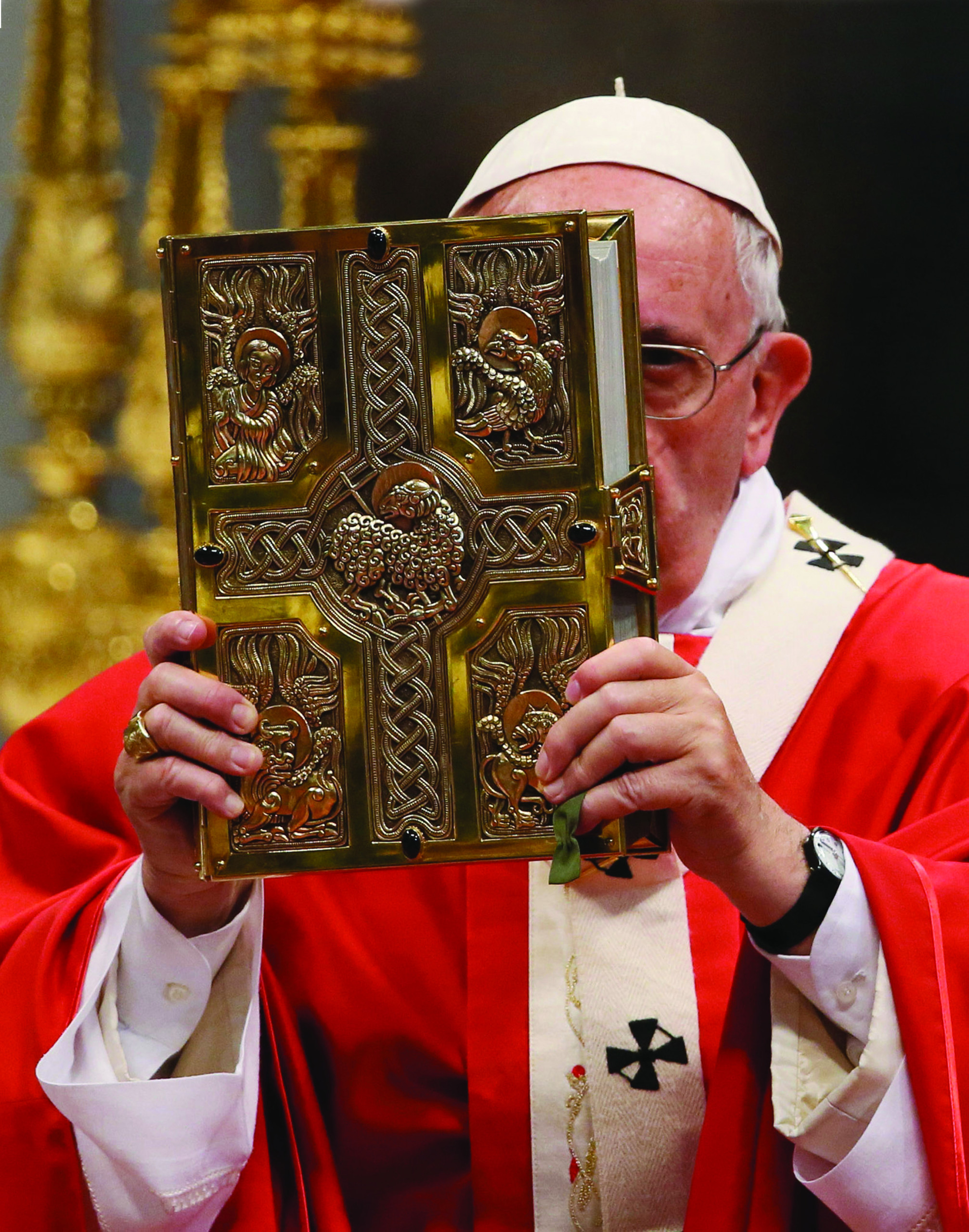

Pope Pius XII.

Prof. Riccardi encouraged other scholars to consider the culture of the day and the context in which any criticism was made. Humanité and other communist newspapers attacked Pius XII as the “Pastor of the Nazis.” This campaign continued into the 1960s and beyond. We need to look past the myths.

There have been arguments that Pius XII was a Pope of the Old Testament while John XXII was a Pope of the New Testament. Prof. Riccardi explained that this is also a myth. Pius was very influential in 20th century Catholic Church history. His work was the most cited source in the documents of Vatican II after the Bible. To understand the modern Church, we must understand him. Prof. Riccardi then addressed the forthcoming opening of archives. He noted that contemporary history does not wait for the opening of archives. While many urge the immediate opening of these archives, he noted that the archives of Pope Pius X (1903-1914) are not yet even fully opened. There are, however, other archives and other sources of information that historians can use to reach fair conclusions.

Prof. Riccardi noted that the cultural landscape and the reputation of Pope Pius XII both changed in the 1960s. That is when the “black legend” – the caricature of Hitler’s Pope – began. He discussed the work of Carlo Falconi, author of an early book critical of Pius XII that was based on documents from Croatia. We now, of course, know that those documents had been fabricated to facilitate the show trial of Cardinal Alojzije Stepinac. Unfortunately, Falconi’s book remains often cited by critics of Pius XII.

Prof. Riccardi said that one result of the false depiction of Pius XII is that there is less public devotion to him today than one might expect. Prof. Riccardi noted that as early as 1982 he took part in a conference that sought to go from myth to truth, and he encouraged the attendees at the conference in Rome to fight against the black legend.

Father Gerald Fogarty.

Fr. Gerald Fogarty S.J., from the University of Virginia, spoke briefly. He is perhaps best known as a member of the Catholic-Jewish study group established in 1999 by leaders from the Pontifical Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews and the International Jewish Committee for Interreligious Consultation, to study the already-released Vatican archival documents. That venture collapsed without any significant achievement. Fr. Fogarty referred to it as the “disastrous Catholic-Jewish Commission.”

Fr. Fogarty reported that he has the diary of a Catholic priest from that era named Fr. McCormack. The diary is critical of Pius XII’s deliberative, diplomatic approach to the events that were unfolding. Fr. Fogarty also said that Fr. McCormack’s comments went “back and forth,” and this shows that we always need to look at historical events in context.

The conference was opened up for comments from the floor, and short comments were offered by journalist Andrea Tornielli and Deacon Dominiek Oversteyns. Of particular interest were the observations that local security services in communist Yugoslavia used false documents to spread the “black legend,” and that the Pius XII’s Vatican sent a letter into Hungary condemning the deportation of Jews, but it was not widely distributed, so few people know of it.

Eduardo Husson pointed out that Nazi propaganda, not the truth, convinced some Poles that the Pope had abandoned them. He also pointed to a speech made by Adolf Hitler on January 30, 1939. In that speech, Hitler made clear that interventions would only make things worse. Prof. Husson said that this explains the diplomatic approach that Pius XII used to help the Jews and others (including imprisoned Catholic priests). Prof. Riccardi reminded people to look for code words in statements made by the Pope.

Anna Foa.

After a short break, Professor Anna Foa of the Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza” spoke on Rome, the Church and the Jews: A Century-old Relationship History. She noted that the popular myth of the black legend is still prevalent, despite much evidence that proves Pius XII was a friend to the Jews. In fact, she noted that the black legend emerged among the Catholics while the “pink legend” (of Pius XII’s goodness) emerged among the Jews. Her theory is that Catholics hold their own to very high standards, but she wondered whether documents from the archives would change minds. (Her pink legend theory was also the subject of an article in L’Osservato Romano on the day of the conference.) She noted that the “Acts and Documents” collection (11 volumes of archival documents selected by a team of Jesuits) is already available, but few critics rely on them.

Prof. Foa noted that there are many unanswered questions, and she wondered what light the about-to-open archives would reveal about things like the roundup of Roman Jews on October 16, 1943 and the apparent “double game” played by Ernst Freiherr von Weizsäcker, the German ambassador to the Holy See. She noted that rescuers often say that they acted at the direction of the Pope. Will the archives prove it? What will the archives reveal about the impact on the Jewish community when the chief rabbi of Rome converted to Catholicism after the war? Perhaps the archives will give us a new image of the Shoah.

Prof. Foa noted that the controversy over Pius XII arose after he died, when The Deputy was first staged in West Berlin by communists from East Germany. She said: “We know The Deputy is the fault of the political influence of East Germany.” The play was banned in Rome, but it was soon published, produced, and promoted in nations around the world, particularly in communist nations, where school children often were expected to view it on an annual basis.

Ronald Rychlak from the University of Mississippi briefly spoke to make two points. First, he said that it is good to open the archives, but there is enough evidence already available to make a reasoned judgment about Pope Pius XII. Second, Prof. Rychlak noted that different approaches might be needed to achieve good results in different areas. He explained that Pius relied on his bishops to provide guidance about how best to proceed. Thus, the American bishops were very outspoken in a statement they issued in the autumn of 1942, expressly condemning the treatment of the Jews and invoking the authority of Pope Pius XII. In Poland, however, the bishop burned the letter from the Pope, explaining in a return letter that reading this statement publically would result in a severe retaliation. This is a reflection of the Catholic doctrine of subsidiarity. Thus, decisions as to how strongly to protest were made not from the Vatican but from the people closest to the events.

Matteo Napolitano spoke briefly, pointing out that there is no question about the Pope having assisted the Jews in France. He also sent money to help victims in France, Romania, and refugees in Spain. (Prof. Limore Yagil later said that Pius was “fully engaged” in these efforts.) Prof. Napolitano also noted the Soviet opposition to Pius, the political propaganda from communist Poland, and false documents from communist Yugoslavia that, among other things, has tainted his reputation and led to the black legend that developed in the 1960s.

Vatican Archivist Johan Ickx spoke next about a paper that he has been developing on Austrian Bishop Alois Hudal, who has been charged with harboring Nazi sympathies because he helped some war criminals escape justice at the end of the war. Dr. Ickx calls Hudal a “legend within the legend.” He helped whoever sought help, whether it was Jews during the war or Germans after the war. He kept Jews and other victims in his personal house. He assisted Germans in Rome who were opposed to the Nazis. Ickx believes that Hudal was simply the easiest target (and best tool) for those who wanted to construct the black legend of Pius XII.

Ickx pointed out that Hudal’s archives prove that he and Pius XII made many efforts to save Jews. In Romania, for instance, thousands of baptismal certificates and 1.5 million lira were given to persecuted Jews. Pope Pius XII’s nephew worked directly with Hudal, and the two of them were very instrumental in putting a halt to the roundup of Roman Jews in October 1943. After their interventions, the arrests immediately stopped, were not repeated, and many who had been arrested were released.

Michael Hesemann, from Pave The Way Foundation, spoke on Pius XII and the Armenian Genocide: A Study on Papa1 Reactions. Hesemann believes that the key to understanding Pius XII – his hesitation to name murderers and victims and his dedication to save as many lives as possible – is the Vatican’s diplomacy during World War I and Benedict XV’s unsuccessful attempt to save the Armenians by an open protest during the genocide of 1915-18. That effort failed, so Pius XII did not want to repeat that mistake.

Limore Yagin of the Université Paris IV-Sorbonne then spoke on The Catholic Church and the Rescue of the French Jews in the Vichy Era. She noted that only about 25 percent of the Jews in Vichy, France were deported, and the Church played an important role in keeping that number low. Many bishops helped, opposing roundups, encouraging rescue efforts, and issuing false baptismal certificates.

Prof. Yagin noted that the Church itself was suffering. Pius opted for diplomacy because he saw that confrontation had backfired elsewhere. Importantly, from 1939 on, the Vatican provided financial assistance to French Jews through various Catholic organizations. Prof. Yagin noted, however, that the real support, inspiration, and direction came from the Vatican. It was “fully engaged” in the rescue efforts.

J.h.M. Bank of the Universiteit Leiden presented a short paper entitled The Church and the Rescue of Jews in France. He explained that similar efforts could lead to very different results depending on the whether the efforts took place in an allied nation (Vichy France) or an occupied nation (Holland). Prof. Bank offered a comparison between two archbishops who became well-known because of their public protest against the deportations of Jews. The first was the Archbishop of Toulouse, Jules-Geraud Saliege. On August 23, 1942, clergy read a letter from the pulpit in which he condemned the deportations of men and women, mothers, and fathers as if they were a herd of cattle. “Jews are our brothers and sisters,” the archbishop went on to say; “a Christian should never forget that.”

Shortly after promulgation of this letter, Pierre Laval, prime minister and the most powerful politician in the Vichy government, summoned the Vatican’s representative to his office. Laval was furious and said that he intended to deport all foreign Jews. He warned the Vatican envoy that those who were hiding on Church properties could be removed by force. Ultimately, however, there was no direct retaliation.

On the other hand, in Holland, a similar letter from the Archbishop of Utrecht, Johannes de Jong, resulted in the issuance of orders for the deportation of the Jews who had been baptized Catholic. Up until that time, a Jew holding a Catholic baptismal certificate was recognized as a Catholic under the terms of the concordat and was exempt from deportation. Now the Catholic certificate did no good. A total of 694,245 Jews were arrested, the majority of whom were deported in haste to Auschwitz and ‘preferentially’ murdered. All Catholic priests and religious sisters with a Jewish background were deported, including the well-known theologian Edith Stein, today known as St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. Jews who had been baptized as Protestants were exempt.

Prof. Bank noted that after the war Pope Pius XII made both of the outspoken archbishops cardinals, even though their dioceses were not traditionally linked to that status. In other words, Pius rewarded their efforts to oppose the Nazis, even though it did not work out well in Holland.

A question-and-answer session brought up the issue of the baptism of Jewish children. Prof. Foa and other commentators explained that sometimes Jewish children – and adults – were baptized not out of a desire to convert but as a means of protection from the Nazis. In virtually every case, this was a voluntary matter and not something that Church officials or other Catholics forced on the Jews.

Picking up on the discussion of Ernst von Weizsäcker, Fr. Fogarty set forth a strong rebuttal to those who have used his activity to indict the Pope. This related to the roundup of Roman Jews in October 1943. Weizsäcker wrote to Berlin that the Pope was not complaining about this event, even though it occurred “under his very windows.” Fr. Fogerty explained that Pius did indeed object as soon as he became aware of the roundup. (Critics have charged that he had advance knowledge of it, but they have never produced any evidence to support the charge.) Pius certainly cared about what was happening, and Weizsäcker was playing a political game to protect himself.

Of significant importance, the papers of former CIA director Allan Dulles are now available online. They reveal that the advice from the United States to Pius XII was never to condemn Hitler lest his retaliation make things worse. This seems to cry for more research, but it may be that Pius XII’s diplomatic approach was driven by a desire to cooperate with the Allies.

Prof. Rychlak spoke again, noting the communist disinformation that had been mentioned by other speakers, including propaganda in Poland, false documents spread by security services in Yugoslavia, and communist newspapers in France and elsewhere that linked Pius with the Nazis. He reiterated Prof. Foa’s observation that The Deputy was the product of East German communist political influence, and explained that the co-author of his most recent book, Disinformation, was the number two man in Communist Romania under Nicolae Ceaușescu, and he had been involved in a disinformation campaign built around that play.

Others have noted the impact and the impeccable timing of The Deputy. As John Jay Hughes wrote in the August 17, 2013 issue of ITV:

Seldom can a work of fiction have appeared at a time more favorable to its message. The 1960s saw publications proclaiming “the death of God” by liberal Christian theologians and at least one rabbi. It was also the age of the Youth Revolution, with the slogan, “Don’t trust anyone over 30.” A play which purported to unmask one of the world’s leading moral authorities was a godsend to the propagators of these new and exciting ideas.

Prof. Rychlak explained that the timing was not coincidental and the change in perception was not organic; it was constructed.

The play’s German and American producers, the German production company, the French translator, the German and American publishers, and other important people around the play were committed communists. Prof. Rychlak also pointed out that Soviet money was used to publish, produce, promote, and finance the play. He encouraged scholars from other nations to look for similar ties between communism and The Deputy in their nations.

Fr. Fogarty spoke briefly, noting that some priestly orders operated like the Underground Railroad from slavery times in the United States. They would move Jewish refugees around from one hidden location to another. He knows that this happened with the Dominicans.

An interesting point that came up during the general discussion period was Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, a Protestant village in Haute-Loire in southern France. During World War II, it became a haven for Jews fleeing from the Nazis and their French collaborators. In fact, the village itself is listed among the Righteous Among Nations at Yad Vashem. With what is known about Jews who were sheltered in Vatican City and Castel Gandolfo, one might wonder whether they should also be listed there.

Matteo Napolitano then spoke on Vatican Diplomacy in the Second World War. He explained that the Church’s focus is always on human rights and the rights of man. Belligerents, on the other hand, think first about winning the war, and only secondarily about the treatment of people. For them, winning is the priority.

Prof. Napolitano explained that during the war the Holy See was a true custodian of peace. More important than winning the war was helping people relocate to places they would be safe. In addition to helping with things like baptismal certificates, the Holy See helped refugees get visas to nations that did not want to “complicate” their dealings with Germany.

While the Church was neutral and humanitarian, the election of Pope Pius XII in 1939 had been recognized as a victory for the democracies. His first encyclical, released just weeks after the outbreak of World War II, was Summi Pontificatus (Darkness over the Earth). In it, Pius made reference to “the ever-increasing host of Christ’s enemies,” and noted that these enemies of Christ “deny or in practice neglect the vivifying truths and the values inherent in belief in God and in Christ” and want to “break the Tables of God’s Commandments to substitute other tables and other standards stripped of the ethical content of [Christianity].” Pius also said that Christians who fell in with the enemies of Christ suffered from cowardice, weakness, or uncertainty.

Prof. Napolitano noted that Summi Pontificatus came as a “relief” to the Western powers. It was the first true condemnation of the Nazi Movement against an innocent country (Poland), and in it, Pius XII made express reference to the Jews, saying:

“The spirit, the teaching and the work of the Church can never be other than that which the Apostle of the Gentiles preached: ‘putting on the new (man) him who is renewed unto knowledge, according to the image of him that created him. Where there is neither Gentile nor Jew, circumcision nor uncircumcision, barbarian nor Scythian, bond nor free. But Christ is all and in all’” (Colossians 3:10, 11).

Since this was Pius XII’s first public statement, the equating of Gentiles and Jews was hugely important and deeply offensive to the Nazis.

To the consternation of German leaders, the Holy See refused to recognize the legitimacy of Nazi conquests. It never acknowledged the disappearance of Poland, Yugoslavia, or the Baltic nations from the map. Pope Pius XII kept Vatican ambassadors to those nations in place.

Prof. Napolitano asked about the myth of Pius XII’s silence. When did the silence start? In the 1930s? With the Shoah? What of the Jews who left Germany in the 1930s? Did they say anything? Was that their duty? The democracies did not speak out; nor did any other nations. In 1933 the World Jewish Congress asked nations to support an embargo against Germany. The United States, France, and Britain all opposed it.

Despite the racial laws adopted in the 1930s, Europeans thought of Germany as a civilized nation. Pius was not as easily misled. As early as 1937 he warned diplomats that Hitler was a pagan. As Pope, he encouraged them to trust Jewish sources of information, even though many thought the horrific stories being told were just wartime propaganda.

After the war, Pius fell victim to a propaganda war that was run from Moscow. Propaganda against anti-communist cardinals came first. Radio Moscow called for a new kind of Pope, one who could “realize the hope of the World.” Of course, as Prof. Napolitano explained, they wanted one that would collaborate with the USSR. This was the true beginning of the black legend.

Prof. Napolitano concluded by noting that the horror of the Shoah was not possible outside of the context of a world war. Historians must strive for historical accuracy. He hopes that the opening of new archives will bring forth greater clarity, but not all the questions will be resolved. Many of the issues are false; we can prove that from documents already available in other archives. We need honesty and accuracy in evaluation. That, not just archival research, will help us know the truth.

Fr. Paul Molinari, who long served as the postulator of Pius XII’s sainthood cause, passed away earlier this year, and Fr. Peter Gumpel, the 91-year-old relator of the cause, has retired. So Fr. Marc Lindeijer, Assistant to the General Postulator of the Society of Jesus, has assumed those duties. Fr. Lindeijer spoke briefly to thank the participants and organizers of the conference, and he encouraged further research and historical scholarship, especially into the archives that are expected to open in the next year.

Hitler’s threat

Adolf Hitler.

Hitler’s Threat Appearing before the Nazi Reichstag on the sixth anniversary of his coming to power, January 30, 1939, Hitler gave a speech in which he make a public threat against the Jews:

“In the course of my life I have very often been a prophet, and have usually been ridiculed for it. During the time of my struggle for power it was in the first instance only the Jewish race that received my prophecies with laughter when I said that I would one day take over the leadership of the State, and with it that of the whole nation, and that I would then among other things settle the Jewish problem. Their laughter was uproarious, but I think that for some time now they have been laughing on the other side of their face. Today I will once more be a prophet: if the international Jewish financiers in and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the Bolshevizing of the earth, and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!” “Germans, resist! Don’t buy from Jews!”

How important are the archives?

How Important Are the Archives? In a recent review written for The Times Literary Supplement (entitled Pope Pius XII, Hitler’s Pawn?), papal critic John Cornwell made much of the fact that two recent books quoted Pius XII’s private secretary, Fr. Robert Leiber, SJ. Late in his life, when asked whether he thought Pacelli was a great saint, he allegedly responded: “Great, yes… a saint, no.”

Of course, for the historian, the assessment of “great” is the matter of importance, not whether he was a saint. More importantly, this language is not archival. It comes word-of-mouth as something Fr. Leiber may have said in a question-and-answer session at a talk he gave. That did not stop Cornwell or the two authors from latching onto it.

Of course, we have a great deal of clear evidence about Leiber’s assessment of Pius in his writings. The Jewish Telegraphic Agency (May 4, 1966), reported that Leiber said Pius “helped the Jews as much as he could” and “spent his whole private fortune for that purpose.” Leiber said that Pius raised funds to help the Jews and helped thousands to escape to North and South America.

Moreover, Pius “suspended at that time the clausura rules for all religious communities — nuns, brothers, Fathers — in order to permit them to hide as many Jews as possible. Thousands of Jews were saved that way.”

Several years ago, the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace at Stanford University announced that it had many of Leiber’s papers in an archive that was to be unsealed in 2014. The documents were given to the institution in 1983 by Juliusz Stroynowski, who served as secretary in the Polish (Communist) embassy in Rome in the late 1940s. The Hoover Institution also holds Stroynowski’s papers.

There were about ten envelopes in Leiber’s name, with perhaps as many as 1,000 pages that might provide great insight in to the workings of the Vatican during World War II. Those who knew about the cache waited with eager anticipation for the opening in January 2014.

It was quite a letdown. The papers did not actually relate to Leiber. They were mainly private letters between Stroynowski and a woman with whom he seems to have had a romantic relationship. The operating assumption now is that Stroynowski wanted these papers included in his archives at the Hoover Institution, but he feared that if he left them behind, his wife would purge them before handing them over. We trust the new Pius XII archives will prove more enlightening!

The Inner Circle of Pope Pius

The Inner Circle of Pope Pius Conference attendees were provided with a paper written by Dr. Stefan Samerski of Berlin. The title was Pius XII and the German Occupation of Rome 1943/44. In it, he reviewed the papers of Fr. Pancratius Pfeiffer, who acted as a middle man between Nazi commanders and the Vatican during the occupation of Rome. These papers provide an insight into the secret activity of Pope Pius XII’s support for Jews and other people in need in Rome and its surroundings. According to Dr. Samerski, Pius XII relied on a small group of trusted confidants to save lives and to improve the desperate situation throughout Rome. Fr. Pfeiffer’s papers provide a new picture of the Pope and his strategies in dealing with direct (and even personal) threats. This view also gives us a new view of the Germans in Rome. Too often we assume that they were all compliant Nazis. Clearly that was not the case, and it is important to differentiate based this new information.

The Role of the USSR

The Role of the USSR If a new issue could be said to have evolved from the conference, it would seem to be the hand of the Soviet Union and international communism in developing the black legend of Pius XII. Vice-Chancellor Husson, Prof. Riccardi, Andrea Tornielli, Prof. Foa, Prof. Rychlak, and Prof. Napolitano all made reference to Soviet or communist efforts to spread the black legend of Pius XII. This is a fairly new development in Pius XII scholarship, first seriously discussed in Ronald Rychlak’s Hitler, the War, and the Pope (Our Sunday Visitor, revised edition 2010) and then expanded upon in Ion Pacepa’s Disinformation: Former Spy Chief Reveals Secret Strategies for Undermining Freedom, Attacking Religion, and Promoting Terrorism (WND Books, 2013).

As the title suggests, Pacepa gives a first-hand account of his efforts, as head of Communist Romania’s foreign intelligence, to spread disinformation about Pope Pius XII. The aim was not simply to discredit a Pope. Rather, by associating a Pope with the Nazis, Moscow hoped to discredit the Catholic Church, Christianity, and Western values.

Pope Francis View on Pope Pius

Jews taking refuge during World War II.

Pope Francis’ Views on Pope Pius Pope Francis did not appear at the conference, but he has addressed the archives, saying that he will wait for their opening, which “will shed a lot of light,” before deciding on whether to propose Pius XII for sainthood. Francis seems, however, to have tipped his hand regarding his assessment of Pius and the actions that he took, saying that he sometimes gets an “existential rash” when he sees the criticism of Pius XII and the Church. Earlier this year, Francis spoke to reporters about 42 children of Jews and other refugees who were born in the Pope’s personal bed in his summer home, Castel Gandolfo, during the Nazi occupation of Rome. “He hid many in convents in Rome and in other Italian cities, and in the residence of Castel Gandolfo,” said Francis. “Was it better for him not to speak so that more Jews wouldn’t be killed, or for him to speak?”

Statement from 1942

Statement from 1942 At their annual meeting in Washington, D.C., in October 1942, the U.S. Bishops released a statement indicating that the Vatican had come to believe the horrible news coming from Germany and occupied nations:

“Since the murderous assault on Poland, utterly devoid of every semblance of humanity, there has been a premeditated and systematic extermination of the people of this nation. The same satanic technique is being applied to many other peoples. We feel a deep sense of revulsion against the cruel indignities heaped upon Jews in conquered countries and upon defenseless peoples not of our faith…. Deeply moved by the arrest and maltreatment of the Jews, we cannot stifle the cry of conscience. In the name of humanity and Christian principles, our voice is raised.”

Christmas 1944

Christmas 1944 In his 1944 Christmas message, Pope Pius XII defended the punishment of war criminals, but he objected to the collective punishment of nations. In fact, the Vatican actually helped prosecute Nazi war criminals.

In 1946 the Vatican handed over many of its documents to the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, which used them as evidence against the Nazis for persecuting the Catholic Church before and during the war.

Like the Vatican, the International Red Cross has been identified as having helped Nazis escape from justice. It is, however, inconceivable that the Nazis revealed their background to the Church or Red Cross officials. It is even less likely that any such information would have reached the upper echelons of these organizations. The logistics of the massive relocation programs simply made it impossible to investigate most individuals who sought help.

In an interview, Monsignor Karl Bayer, who was liaison chaplain responsible for the 250,000 prisoners of war in the north of Italy explained: “If there really was a screening,” he said, “an attempt at detailed research by examining each of the people concerned, it would have required at least a dozen German-speaking priests. I knew them all. There were, of course, quite a few, but they were incredibly busy — too busy, I think, for the kind of supervision of the many people [they dealt with]…. Well, of course we asked questions,” he said. “But at the same time, we hadn’t an earthly chance of checking on the answers. In Rome, at that time, every kind of paper and information could be bought. If a man wanted to tell us he was born in Viareggio — no matter if he was really born in Berlin and couldn’t speak a word of Italian, he only had to go down into the street and he’d find dozens of Italians willing to swear on a stack of Bibles that they knew he was born in Viareggio….” In a situation like that, it is hard to fault any relief agency for being deceived.

In 1947, a top secret Department of State memorandum entitled Illegal Emigration Movements in and Through Italy identified the Vatican as the largest single organization involved in the illegal movement of emigrants. “Jewish Agencies and individuals” were identified as the second largest group. The memo, however, made clear that all of the agencies, including the International Red Cross, worked in collaboration with one another and that anyone could take advantage of these programs.

In fact, the memo indicated that the Church had no way to identify the politics of the people in the program. Moreover, the memo reported that Vatican and Red Cross passports were easily and commonly falsified by changing the pictures on them.

1942 Christmas Message

1942 Christmas message “Mankind owes that vow [the renewal of society] to the countless dead who lie buried on the field of battle: The sacrifice of their lives in the fulfillment of their duty is a holocaust offered for a new and better social order. Mankind owes that vow to the innumerable sorrowing host of mothers, widows and orphans who have seen the light, the solace and the support of their lives wrenched from them. Mankind owes that vow to those numberless exiles whom the hurricane of war has torn from their native land and scattered in the land of the stranger; who can make their own the lament of the Prophet: “Our inheritance is turned to aliens; our house to strangers.” Mankind owes that vow to the hundreds of thousands of persons who, without any fault on their part, sometimes only because of their nationality or race, have been consigned to death or to a slow decline.” (Pius XII; emphasis ours).

Facebook Comments