(From “L’Espresso” #49, November 28-December 5, 2002)

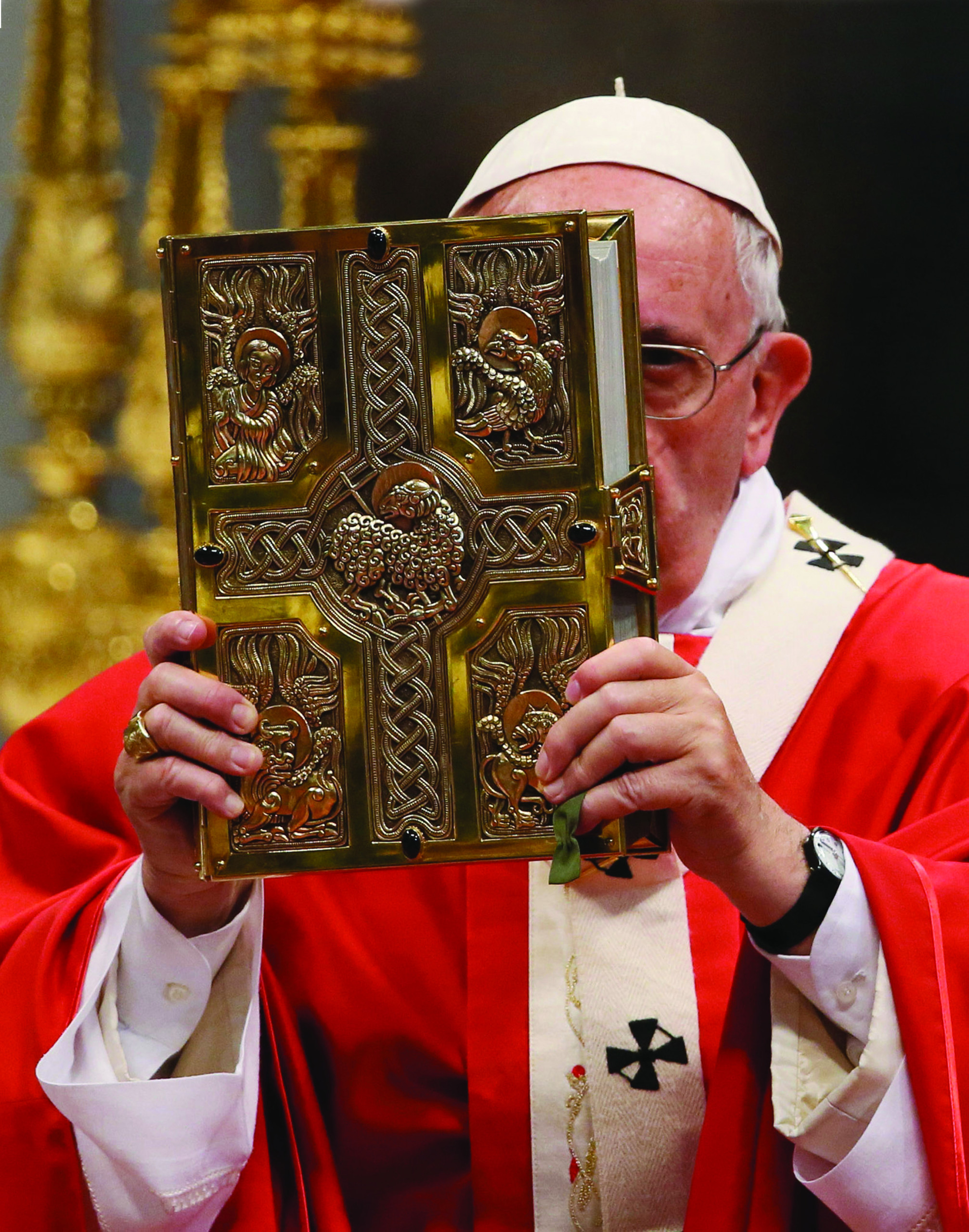

Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Buenos Aires, Argentina, is pictured in an undated file photo. (CNS photo)

Midway through November, his colleagues wanted to elect him president of the Argentinian bishops’´conference. He refused. But if there had been a conclave, it would have been difficult for him to refuse the election to the papacy, because he´is the one the cardinals would vote for resoundingly, if they were called together immediately to choose the successor to John Paul II.

He’s Jorge Mario Bergoglio, archbishop of Buenos Aires. Born in Argentina (with an Italian surname), he has leapt to the top of the list of the papabili, given the ever-increasing likelihood that the next pope could be Latin-American. Reserved, timid, and laconic, he won’t lift a finger to advance his own campaign — but even this is counted among his strong points.

John Paul II made him a cardinal together with the last group of bishops named to the honor, in February of 2001. On that occasion, Bergoglio distinguished himself by his reserve among his many more festive colleagues. Hundreds of Argentinians had begun fundraising efforts to fly to Rome to pay homage to the new man with the red hat. But Bergoglio stopped them. He ordered them to remain in Argentina and distribute the money they had raised to the poor. In Rome, he celebrated his new honor nearly alone — and with Lenten austerity.

He has always lived this way. Since he was made archbishop of the Argentinian capital, the luxurious residence next to the cathedral has remained empty. He lives in a nearby apartment, together with another bishop, old and sickly. In the evening, he himself cooks for both of them. He rarely drives, getting around most of the time by bus, wearing the cassock of an ordinary priest.

Of course, it’s more difficult now for him to move about unnoticed, his face becoming ever more familiar in his country. Since Argentina has spun into a tremendous crisis and everyone else’s reputation — politicians, business leaders, officials, intellectuals — has fallen through the floor, the star of Cardinal Bergoglio has risen to its zenith. He has become one of the few guiding lights of the people.

Yet he’s not the type to compromise himself for the public. Every time he speaks, instead, he tries to shake people up and surprise them. In the middle of November, he did not give a learned homily on social justice to the people of Argentina reduced by hunger — he told them to return to the humble teachings of the Ten Commandments and the Beatitudes. “This,” he explained, “is the way of Jesus.” And as soon as one follows this way seriously, he understands that “to trample upon the dignity of a woman, a man, a child, an elderly person, is a grave sin that cries out to heaven,” and he decides not to do it any more.

The other bishops follow in his footsteps. During the Holy Year of 2000 he asked the entire Church in Argentina to put on garments of public penance for the sins committed during the years of the dictatorship. As a result of this act of purification, the Church had the credibility to be able to ask the nation to acknowledge how its own sins had contributed to its current disaster. At the celebration of the Te Deum at the most recent national feast, last May 25th, there was a record audience for Cardinal Bergoglio’s homily. The cardinal asked the people of Argentina to do as Zacchaeus had done in the Gospel. Here was a sinister loan shark. But, taking account of his moral lowliness, he climbed up into a sycamore tree to see Jesus and let himself be seen and converted by him.

There isn’t a politician, from the right to the extreme left, who isn’t dying for the blessing of Bergoglio. Even the women of Plaza de Mayo, ultraradicals and unbridled anti-Catholics, treat him with respect. He has even made inroads with one of them in private meetings. On another occasion, he visited the deathbed of an ex-bishop, Jeronimo Podestá, who had married in defiance of the Church and was dying poor and forgotten by all. From that moment, Mrs. Podestá became one of his devoted fans.

But Bergoglio has also had his difficulties with his ecclesiastical environment. He is a Jesuit of the old school, faithful to St. Ignatius. He became the provincial superior of the Society of Jesus in Argentina just when the dictatorship was in full furor and many of his confreres were tempted to take up the rifle and apply the teachings of Marx. Once removed from his position as superior, Bergoglio returned to obscurity. He came back into the public eye in 1992 when the archbishop of Buenos Aires, Antonio Quarracino, made him his auxiliary bishop.

From there, his ascent began. The first — and almost only — interview he has given was to a parish news bulletin, Estrellita de Belém, as if to make the point that the Church is in the minority and shouldn’t cultivate illusions of grandeur.

He travels as little as possible. He visits the Vatican only when strictly necessary, the four or five times a year they summon him. He reserves a small room in a residence for clergy (the “Casa del Clero” on Via della Scrofa), and every morning at 5:30 he’s already awake and praying in the chapel.

Bergoglio excels in one-on-one communication, but he can also speak well in public when necessary. At the last synod of bishops in the fall of 2001, they unexpectedly asked him to take the place of one of the speakers who had withdrawn. Bergoglio managed the meeting so well that, at the time for electing the twelve members of the secretary’s council, his brother bishops chose him with the highest vote possible.

Someone in the Vatican had the idea to call him to direct an important dicastery. “Please, I would die in the Curia,” he implored. They spared him.

Since that time, the thought of having him return to Rome as the successor of Peter has begun to spread with growing intensity. The Latin-American cardinals are increasingly focused upon him, as is Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger. The only key figure among the Curia who hesitates when he hears his name is Secretary of State Angelo Cardinal Sodano — the very man known for supporting the idea of a Latin-American pope.

Facebook Comments