Apostolic Exhortation “Amoris Laetitia”

Francis in Amoris Laetitia (“The Joy of Love”) has written a hymn to the joy that the lasting love between a man and a woman in marriage brings. But this love can grow cold, and sorrow over this failure is at the heart of The Joy of Love. And this has led to controversy

The new Apostolic Exhortation of Pope Francis, Amoris Laetitia (“The Joy of Love”) is, in essence, a hymn to marriage and the family. It speaks in beautiful, sometimes touching, terms of the institution of marriage as a natural good which brings love, light and life into the lives of all who participate in it, all who are brought into existence through it, and all who grow to maturity and old age under its protection. “Creating the human race in His own image and continually keeping it in being, God inscribed in the humanity of man and woman the vocation, and thus the capacity and responsibility, of love and communion,” Pope Francis writes. “Love is therefore the fundamental and innate vocation of every human being.”

The Pope also speaks in terms of the sacred, in a profound proclamation that marriage is also a sacrament, and a type and image of the mystical relationship between Christ and His people, the Church. He calls marriage a “real symbol of the event of salvation,” and quotes Pope John Paul II in Familaris Consortio, saying, “As a memorial, the sacrament gives them the grace and duty of commemorating the great works of God and of bearing witness to them before their children. As actuation, it gives them the grace and duty of putting into practice in the present, towards each other and their children, the demands of a love which forgives and redeems. As prophecy, it gives them the grace and duty of living and bearing witness to the hope of the future encounter with Christ.”

But, Amoris Laetitia also has a practical dimension, and it is principally in this that the Pope’s document has encountered perplexity, hesitancy, and even resistance.

Some of the issues that have become lightning rods for controversy have been its discussion of the divorced and civilly remarried, especially vis-à-vis reception of the sacraments; the role of the individual conscience; and the relationship of doctrine to praxis.

It is our purpose here to examine this controversy. To do this, we must of necessity be unfair to the text itself, passing over its riches of wisdom and beauty. We begin by printing the most controversial paragraphs of the text, and continue with a wide sampling of the commentary (sometimes heated) Amoris Laetitia has engendered.

We begin with the official presentation of the document given by Austrian Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, handpicked by Pope Francis to introduce it to the world on April 8, because he is an esteemed Dominican theologian as well as a Prince of the Church, but also because he is the son of divorced parents, and thus one who has experienced firsthand the pain of a broken family.

Cardinal Schönborn said in his presentation that the document changes the terms of “ecclesial discourse” because it contains a “pervasive principle of ‘inclusion’” and so “overcomes the clear distinction between ‘regular’ and ‘irregular’ marriages.”

But he also stressed that any “innovation” in the document takes place “within continuity.”

Following a selection of reactions to Cardinal Schönborn’s remarks, we go on to Cardinal Raymond Burke’s analysis of Amoris Laetitia as not a doctrinal, but a pastoral text —and not a really novel one. It “applies the perennial doctrine and discipline of the Church to the world at the time,” Burke says.

Theologian Pia de Solenni seems to concur with Cardinal Burke in her piece, in which she asserts that the door is “open for those who want healing,” but not for those “who want to circumvent Church teaching.”

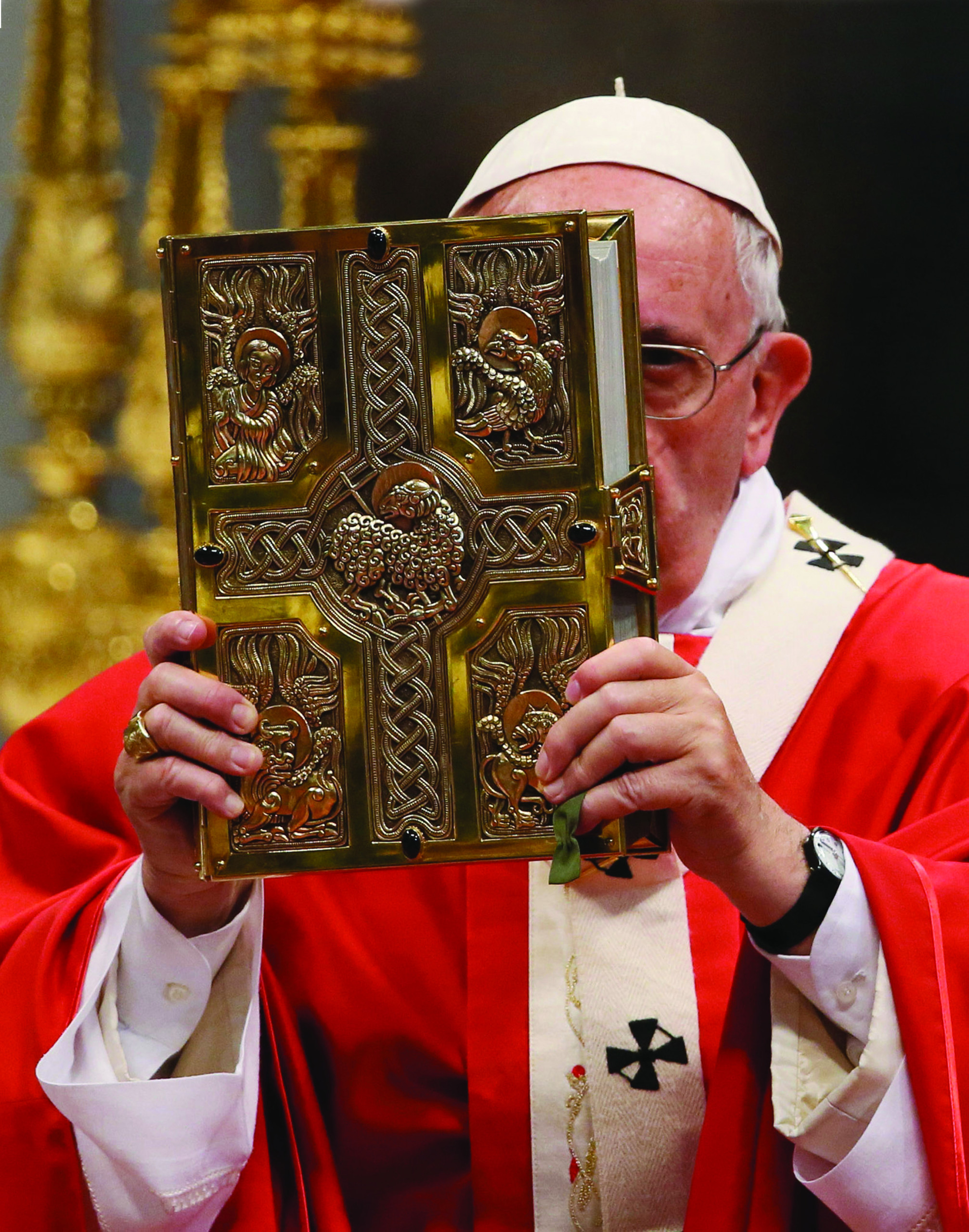

Pope Francis holds a rose and chocolates thrown by a person in the crowd as he arrives for an audience for engaged couples in St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican Feb. 14, Valentine’s Day. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

However, Fr. Brian Harrison, OS, takes a dimmer view of the question of innovation in sacramental practice, saying that “the Holy Father breaks with the teaching and discipline of all his predecessors,” and foresees trouble for priests and bishops who continue to cleave to the traditional sacramental discipline of the Church and are perceived as insufficiently “merciful.”

Perhaps the most explicitly confident that Amoris Laetitia has introduced a new “way forward” for readmittance to the sacraments, including Holy Communion, for those in second, non-canonical marriages, is Fr. Antonio Spadaro, SJ, who edits the Italian Jesuit journal La Civiltà Cattolica and is known to be close to Pope Francis. We excerpt his treatment of the document, in which he argues that the Exhortation “opens the door” to individual discernment in sacramental discipline, leaving behind the traditional “rigorism” of the Church.

Three canon law experts then weigh in with their assessments of Amoris Laetitia; all three conclude that the Exhortation contains no substantial doctrinal innovations. Ed Condon challenges the “received wisdom” that the document proposes any changes in doctrine and discipline. Kurt Martens defends Pope Francis’ use of the term “internal forum” as a place to “discover first that there is a problem.” And Ed Peters reminds us that the law is “made of words, not surmises.”

Fr. James Bradley of the U.K. points out that the “language of accompaniment” that Francis uses is no innovation either — it “further articulates what Pope Benedict wrote in Sacramentum Caritatis,” which in turn referenced the teachings of St. John Paul II.

At loggerheads with these sanguine interpretations of the Exhortation stands Bishop Athanasius Schneider of Kazakhstan, who believes — and illustrates how — the document has sown grave confusion, and contends that “we must respectfully request an authoritative interpretation.”

Fellow Bishops Philip Egan of Plymouth in the U.K. and Charles Chaput of Philadelphia in the U.S. speak about how they will lead their flocks in reflecting upon, and implementing, Amoris Laetitia.

Finally, Germany’s foremost Catholic philosopher, Prof. Robert Spaemann, 89, esteemed by his contemporary, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, also 89, makes the unsettling case that Pope Francis has unwittingly created “chaos by the stroke of a pen,” which may, in fact, be leading the Church “toward schism” if the text is not altered or withdrawn.

So, Pope Francis’ “hymn to marriage” has generated intense debate. It has been written in a particular historical period — 2016 — a little more than a decade after John Paul II left the world stage, and three years after the stunning resignation of Pope Benedict, a towering intellect who had been the Church’s doctrinal guardian under his predecessor. Benedict — as Father, later Cardinal, Joseph Ratzinger — wrote on the question of how to help those in broken marriages as early as 1972, when the sexual revolution was already in full swing. Today, the cultural deterioration spawned by that revolution has left the human psyche battered; we suffer from a kind of deracination; we have been severed from our roots in family life, from the conviction that the marital institution is the central point of stability, coherence, prosperity and, yes, joy, for human society, by a modern cultural understanding of human love as merely a vehicle for “self-fulfillment.”

Are people of today capable of adhering to the lofty ideal of a faithful, permanent, sacrificial, life-long relationship with just one person? Are we asking them for something heroic?

The problems of the family clearly demand the attention of the Church. No one is more acutely aware of this than Pope Francis, who has spoken on family life regularly, and called not one, but two synods of bishops to discuss it. And as the Synods proceeded, it became apparent that there were fault lines in the body of bishops, and also the faithful: some wanted to simply restate what Pope John Paul II taught at length in 1981, in Familaris Consortio; others appeared to want to gradually “develop” those teachings from 1981 — even “change” them. Still others seemed perplexed: they recognized the need to “do something,” hoping it could be done within a coherent development of prior teaching, but they were not sure what that “something” ought to be.

To this uncertainty about marriage between one man and one woman, we add the spectacle of a world wondering if the Catholic Church would at long last support the “rights” to homosexual marriage, or change her teaching on the immorality of contraception and abortion, or on access to Communion for those who had been married, divorced and remarried.

Amoris Laetitia was the result of all of these hopes, expectations, pressures, concerns. And it is generally agreed that it holds the line quite firmly — unexpectedly, compared to predictions — on issues like contraception (Humanae Vitae is reinforced without ambiguity) and homosexual “marriages” (saying such unions are really nothing like true marriages. which must be between people of the opposite sex).

For some, Amoris Laetitia is a beautiful document flawed primarily by one, brief footnote, footnote #351 (see below), which seems to open up the possibility that, due to mitigating circumstances, persons in what appear to be objectively sinful marriages might be still be able to receive Communion. For others, this judgment is incorrect, and this fear unwarranted.

In order to assess who is right, we give you key passages of Amoris Laetitia — in some way distorting the document, it is true, by omitting many beautiful expositions of Catholic doctrine on marriage. But since it is necessary to touch the “sore spot,” to engage in the debate Francis has sparked, we leave aside the passages that are inspiring and heartwarming, and enter into the polemics of this exhortation.

Is Amoris Laetitia a Development or a Contradiction of this Paragraph of St. John Paul II?

Here is the key paragraph in the 1981 Apostolic Exhortation of Pope John Paul II, Familiaris Consortio. In it, John Paul deals with the question of divorced and remarried Catholics and their reception of Communion

Familiaris Consortio, John Paul II, 1981, Par. 84

Together with the Synod, I earnestly call upon pastors and the whole community of the faithful to help the divorced, and with solicitous care to make sure that they do not consider themselves as separated from the Church, for as baptized persons they can, and indeed must, share in her life. …

However, the Church reaffirms her practice, which is based upon Sacred Scripture, of not admitting to Eucharistic Communion divorced persons who have remarried. They are unable to be admitted thereto from the fact that their state and condition of life objectively contradict that union of love between Christ and the Church which is signified and effected by the Eucharist. Besides this, there is another special pastoral reason: if these people were admitted to the Eucharist, the faithful would be led into error and confusion regarding the Church’s teaching about the indissolubility of marriage.

Reconciliation in the sacrament of Penance which would open the way to the Eucharist, can only be granted to those who, repenting of having broken the sign of the Covenant and of fidelity to Christ, are sincerely ready to undertake a way of life that is no longer in contradiction to the indissolubility of marriage. This means, in practice, that when, for serious reasons, such as for example the children’s upbringing, a man and a woman cannot satisfy the obligation to separate, they “take on themselves the duty to live in complete continence, that is, by abstinence from the acts proper to married couples.”[180]

Documents

AMORIS LAETITIA

Here Are the Most Controversial Paragraphs in Amoris Laetitia. All Are from Chapter 8, the Final Chapter of the Document

298. The divorced who have entered a new union, for example, can find themselves in a variety of situations, which should not be pigeonholed or fit into overly rigid classifications leaving no room for a suitable personal and pastoral discernment. One thing is a second union consolidated over time, with new children, proven fidelity, generous self-giving, Christian commitment, a consciousness of its irregularity and of the great difficulty of going back without feeling in conscience that one would fall into new sins. The Church acknowledges situations “where, for serious reasons, such as the children’s upbringing, a man and woman cannot satisfy the obligation to separate.”329 There are also the cases of those who made every effort to save their first marriage and were unjustly abandoned, or of “those who have entered into a second union for the sake of the children’s upbringing, and are sometimes subjectively certain in conscience that their previous and irreparably broken marriage had never been valid.”330 Another thing is a new union arising from a recent divorce, with all the suffering and confusion which this entails for children and entire families, or the case of someone who has consistently failed in his obligations to the family. It must remain clear that this is not the ideal which the Gospel proposes for marriage and the family. The Synod Fathers stated that the discernment of pastors must always take place “by adequately distinguishing,”331 with an approach which “carefully discerns situations.”332 We know that no “easy recipes” exist.333

329 – John Paul II, Apostolic Exhortation Familiaris Consortio (22 November 1981), 84: AAS 74 (1982), 186. In such situations, many people, knowing and accepting the possibility of living “as brothers and sisters” which the Church offers them, point out that if certain expressions of intimacy are lacking, “it often happens that faithfulness is endangered and the good of the children suffers” (Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World Gaudium et Spes, 51).

330 – Ibid.

331 – Relatio Synodi 2014, 26.

332 – Ibid., 45.

333 – Benedict XVI, Address to the Seventh World Meeting of Families in Milan (2 June 2012), Response n. 5: Insegnamenti VIII/1 (2012), 691.

301. For an adequate understanding of the possibility and need of special discernment in certain “irregular” situations, one thing must always be taken into account, lest anyone think that the demands of the Gospel are in any way being compromised. The Church possesses a solid body of reflection concerning mitigating factors and situations. Hence it can no longer simply be said that all those in any “irregular” situation are living in a state of mortal sin and are deprived of sanctifying grace. More is involved here than mere ignorance of the rule. A subject may know full well the rule, yet have great difficulty in understanding “its inherent values,”339 or be in a concrete situation which does not allow him or her to act differently and decide otherwise without further sin. As the Synod Fathers put it, “factors may exist which limit the ability to make a decision.”340 Saint Thomas Aquinas himself recognized that someone may possess grace and charity, yet not be able to exercise any one of the virtues well;341 in other words, although someone may possess all the infused moral virtues, he does not clearly manifest the existence of one of them, because the outward practice of that virtue is rendered difficult: “Certain saints are said not to possess certain virtues, in so far as they experience difficulty in the acts of those virtues, even though they have the habits of all the virtues.”342

302. The Catechism of the Catholic Church clearly mentions these factors: “imputability and responsibility for an action can be diminished or even nullified by ignorance, inadvertence, duress, fear, habit, inordinate attachments, and other psychological or social factors.” 343 In another paragraph, the Catechism refers once again to circumstances which mitigate moral responsibility, and mentions at length “affective immaturity, force of acquired habit, conditions of anxiety or other psychological or social factors that lessen or even extenuate moral culpability.” 344 For this reason, a negative judgment about an objective situation does not imply a judgment about the imputability or culpability of the person involved.345 On the basis of these convictions, I consider very fitting what many Synod Fathers wanted to affirm: “Under certain circumstances people find it very difficult to act differently. Therefore, while upholding a general rule, it is necessary to recognize that responsibility with respect to certain actions or decisions is not the same in all cases. Pastoral discernment, while taking into account a person’s properly formed conscience, must take responsibility for these situations. Even the consequences of actions taken are not necessarily the same in all cases.”346

303. Recognizing the influence of such concrete factors, we can add that individual conscience needs to be better incorporated into the Church’s praxis in certain situations which do not objectively embody our understanding of marriage. Naturally, every effort should be made to encourage the development of an enlightened conscience, formed and guided by the responsible and serious discernment of one’s pastor, and to encourage an ever greater trust in God’s grace. Yet conscience can do more than recognize that a given situation does not correspond objectively to the overall demands of the Gospel. It can also recognize with sincerity and honesty what for now is the most generous response which can be given to God, and come to see with a certain moral security that it is what God himself is asking amid the concrete complexity of one’s limits, while yet not fully the objective ideal. In any event, let us recall that this discernment is dynamic; it must remain ever open to new stages of growth and to new decisions which can enable the ideal to be more fully realized.

Rules and discernment

304. It is reductive simply to consider whether or not an individual’s actions correspond to a general law or rule, because that is not enough to discern and ensure full fidelity to God in the concrete life of a human being. I earnestly ask that we always recall a teaching of Saint Thomas Aquinas and learn to incorporate it in our pastoral discernment: “Although there is necessity in the general principles, the more we descend to matters of detail, the more frequently we encounter defects… In matters of action, truth or practical rectitude is not the same for all, as to matters of detail, but only as to the general principles; and where there is the same rectitude in matters of detail, it is not equally known to all… The principle will be found to fail, according as we descend further into detail.”347 It is true that general rules set forth a good which can never be disregarded or neglected, but in their formulation they cannot provide absolutely for all particular situations. At the same time, it must be said that, precisely for that reason, what is part of a practical discernment in particular circumstances cannot be elevated to the level of a rule. That would not only lead to an intolerable casuistry, but would endanger the very values which must be preserved with special care.

305. For this reason, a pastor cannot feel that it is enough simply to apply moral laws to those living in “irregular” situations, as if they were stones to throw at people’s lives. This would bespeak the closed heart of one used to hiding behind the Church’s teachings, “sitting on the chair of Moses and judging at times with superiority and superficiality difficult cases and wounded families.”349 Along these same lines, the International Theological Commission has noted that “natural law could not be presented as an already established set of rules that impose themselves a priori on the moral subject; rather, it is a source of objective inspiration for the deeply personal process of making decisions.”350 Because of forms of conditioning and mitigating factors, it is possible that in an objective situation of sin — which may not be subjectively culpable, or fully such — a person can be living in God’s grace, can love and can also grow in the life of grace and charity, while receiving the Church’s help to this end.351 Discernment must help to find possible ways of responding to God and growing in the midst of limits. By thinking that everything is black and white, we sometimes close off the way of grace and of growth, and discourage paths of sanctification which give glory to God. Let us remember that “a small step, in the midst of great human limitations, can be more pleasing to God than a life which appears outwardly in order, but moves through the day without confronting great difficulties.”352 The practical pastoral care of ministers and of communities must not fail to embrace this reality.

339 – John Paul II, Apostolic Exhortation Familiaris Consortio (22 November 1981), 33: AAS 74 (1982), 121.

340 – Relatio Finalis 2015, 51.

341 – Cf. Summa Theologiae I-II, q. 65, art. 3 ad 2; De Malo, q. 2, art. 2.

342 – Ibid., ad 3.

343 – No. 1735.

344 – Ibid., 2352; Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Declaration on Euthanasia Iura et Bona (5 May 1980), II: AAS 72 (1980), 546; John Paul II, in his critique of the category of “fundamental option,” recognized that “doubtless there can occur situations which are very complex and obscure from a psychological viewpoint, and which have an influence on the sinner’s subjective culpability” (Apostolic Exhortation Reconciliatio et Paenitentia [2 December 1984], 17: AAS 77 [1985], 223). 234

345 – Cf. Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts, Declaration Concerning the Admission to Holy Communion of Faithful Who are Divorced and Remarried (24 June 2000), 2.

346 – Relatio Finalis 2015, 85.

347 – Summa Theologiae, I-II, q. 94, art. 4.349 – Address for the Conclusion of the Fourteenth Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops (24 October 2015): L’Osservatore Romano, 26-27 October 2015, p. 13.

350 – International Theological Commission, In Search of a Universal Ethic: A New Look at Natural Law (2009), 59.

351 – In certain cases, this can include the help of the sacraments. Hence, “I want to remind priests that the confessional must not be a torture chamber, but rather an encounter with the Lord’s mercy” (Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium [24 November 2013], 44: AAS 105 [2013], 1038). I would also point out that the Eucharist “is not a prize for the perfect, but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak” (ibid., 47: 1039).

352 – Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium (24 November 2013), 44: AAS 105 (2013), 1038-1039.

Facebook Comments