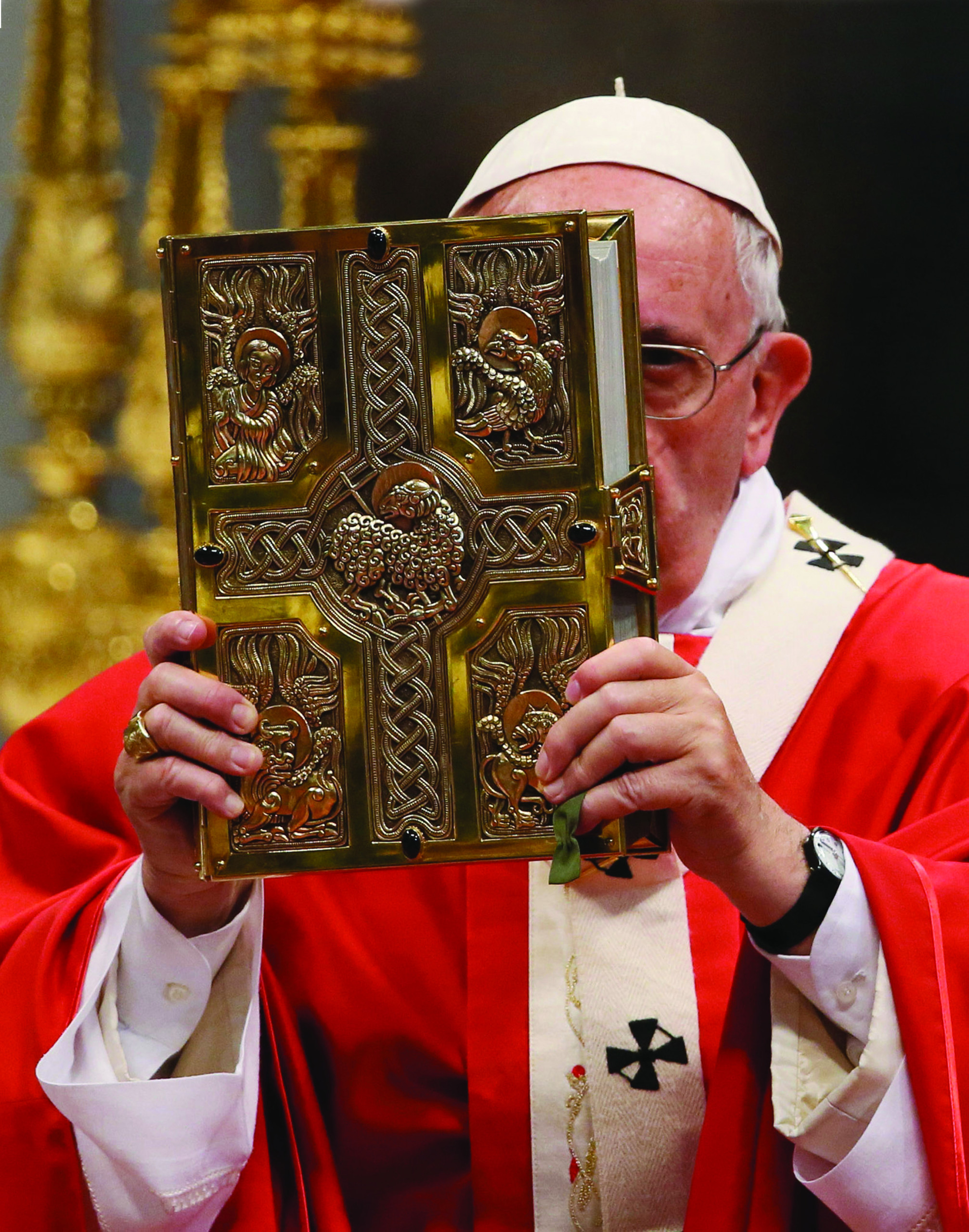

Pope Francis at the Synod on the Family

The “received wisdom” is that the Pope’s document is about Communion for the divorced and remarried, but is it really so?

You could be forgiven for having decided that Amoris Laetitia is a failed document. If you accept, as it seems to be the received wisdom to do, that its purpose is to resolve the debate about how doctrine and discipline should be changed to allow the civilly remarried to receive Communion, it is hard to see it any other way.

But how did this happen?

It was all supposed to be so clear. Before pen was even put to paper, a small group in the papal orbit, led by Cardinal Kasper, were telling the world, in strikingly bold terms, that the exhortation would be revolutionary, an historic turning of the page; it would, most especially, be definitive on the issue of Communion for the divorced and remarried.

This rhetoric now looks overblown, putting it mildly, and, while the debate over what it actually says rages on, I have yet to encounter anyone who can say with a straight face that Amoris Laetitia is definitive. But how can this be?

We were assured that these predictions were coming from people with direct access to the Pope’s thinking on the subject, so there must be an explanation for the lack of any clear change to sacramental doctrine or discipline on Communion for the civilly remarried.

The explanations which have been advanced by those who claim either to speak for the Pope, or to understand his true intentions, essentially follow one of three lines of argument:

First: Francis wanted to go further and be much more explicit in the text. He was fully prepared to make a bold, unmistakable break with previous teaching and say clearly that the civilly remarried can take Communion. But, in the final reckoning, he could not bring himself to face the fight with “conservatives” that would have ensued; so he bowed to pressure and fudged the issue.

Second: The Pope has, actually, tried to construct a nifty new rationale for admitting the civilly remarried to Communion through the application of certain intellectual, theological, and canonical methodologies, like diminished responsibility and the law of gradualness. By cleverly using selective quotations from documents like Familiaris Consortio and the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts’ Declaration Concerning the Admission to Holy Communion of Faithful Who are Divorced and Remarried, he invokes disciplinary touchstones but in such a way as to reverse their meaning. This cunning piece of intellectual sleight-of-hand allows him to make a clear case for admitting the civilly remarried to Communion, but in such a way that he still appears to be in line with St. John Paul II and the teaching of the Church.

Third: Pope Francis believes that admitting the civilly remarried to Communion is not only pastorally correct but doctrinally and intellectually coherent. The undeniable contradictions between this and the various citations in the text of Amoris Laetitia are an unfortunate, but excusably unimportant, byproduct of the fact that Francis is not some pointy-headed intellectual, he is a pastor; he is not the kind of Pope who writes seamless and impenetrable theological treatises, and that is a good thing. He swirls up the teaching of the Church, meditates upon it, and is inspired to produce something new.

To sum up: the rationale for Amoris Laetitia permitting the admission of the civilly remarried to Communion in a way which goes beyond the provisions of current practice, and doing so in an impossibly vague manner, hinges on the Pope being either weak, disingenuous, or stupid. These presumptions are as scandalous as they are wrong. I propose an alternative: the Pope did exactly what he set out to do, no more, no less.

Let us begin from basic principles. Why must Amoris Laetitia permit the civilly remarried to receive Communion? In fact, why must we assume it addresses the issue at all? When you boil it down, the answer is, “Because some people have told us that it does.” But what if they are wrong? What if they hope that simply by saying it out loud enough times, it becomes fact?

Here is an interesting exercise: try and interpret Amoris Laetitia using only what Pope Francis has actually said, and exclude from consideration everything someone has said he said, or was going to say: just Francis, in his own words.

Let’s consider what Francis said when the first session of the Synod on the Family opened in 2014. There was already widespread discussion that the Synod was going to facilitate some radical change in the doctrine and/or practice of the faith, and while open discussion was fine, Francis was clear in his opening address that the Synod “unfolds with and under Peter; the presence of the Pope is a guarantee for all and a safeguard of the faith.” He saw his role as a moderator and defender of the faith, not an innovator. At the session’s closing, he famously warned against “a destructive tendency to goodness, which in the name of a deceptive mercy binds the wounds without first curing them… that treats the symptoms and not the causes.” He called this “the temptation of the so-called progressives and liberals.”

Right from the beginning of the synodal process, then, Pope Francis seems to have been both aware of the move for a relaxation of discipline in the name of “mercy” and set himself against it.

The second session of the synod, held last October, concluded with a genuine summary of its purpose, to the mind of the Pope, and perhaps the single most authentic and coherent preview of the text of his eventual exhortation: “The Synod was not about finding exhaustive solutions for all the difficulties and uncertainties which challenge and threaten the family… It was about urging everyone to appreciate the importance of the institution of the family, and of marriage between a man and a woman, based on unity and indissolubility.” By this measure, far from being vague, off-topic, or a failure, Amoris Laetitia is a direct hit.

But wait, though, what are we to make of the common and constant calls for greater, even full, integration of remarried couples into the life of the parish and the Church? This too has come from the Pope directly; surely it must mean something? Indeed it does. But we should recall that “Integration into the Church does not mean taking Communion.” We know this because that is what Pope Francis said to a reporter who asked him about it on the way back to Rome from Mexico, verbatim.

Francis has been clear that couples in this difficult situation need to be welcomed, and have it underscored that they are not there under sufferance. The call for their integration is a necessary one, and the crisis of pastoral care for them is acute. Many pastors are prone to the “deceptive mercy” Francis warned the synod against. Others genuinely struggle to find a way of articulating to them the truth of the Church’s teaching, which is itself beneficial to them, in a way which is both loving and personal and which can take some account of the possibility that they have no idea what’s wrong with their situation.

Francis’ lengthy discussion, in Amoris Laetitia, about the formation of conscience and relative culpability is not about explaining away sin. On the contrary, it’s about the very real fact that many people need the basic concepts of the faith explained to them, as if for the first time, and need to be brought to a realization of the truth of their situation, even slowly, and only then to its necessary resolution. It is a pastoral path leading, maybe, to the Communion rail, but only through the confessional and in fulfillment of the standing discipline of the Church. This is, after all, what the famous footnote 351 actually says, together with the rest of the text of Amoris Laetitia. It’s also what Cardinal Schönborn said in his presentation of the document, and Pope Francis, who is as fed up with talking about this subject as many of us are with hearing about it, has referred all further questions on the subject to him.

Pope Francis has said publicly that he is “annoyed” at the way people insist on trying to focus attention on Communion for the divorced and remarried. This is understandable: instead of taking an excellent exhortation to love and champion marriage on Francis’s own terms, we have taken the bait, dangled by Cardinal Kasper and a few others, to have a seething fight over something the Pope couldn’t care a footnote about. The loss is ours.

Ed Condon holds a doctorate in canon law, which he practices in the tribunals of a number of dioceses. He is a frequent contributor to the London Catholic Herald. He previously spent several years working in British politics.

(This Dossier will be continued in the next issue.)

Facebook Comments