“You’re here before your time,” says the world to Jesus. “Get lost, and take your shabby followers with you.”

By Anthony Esolen

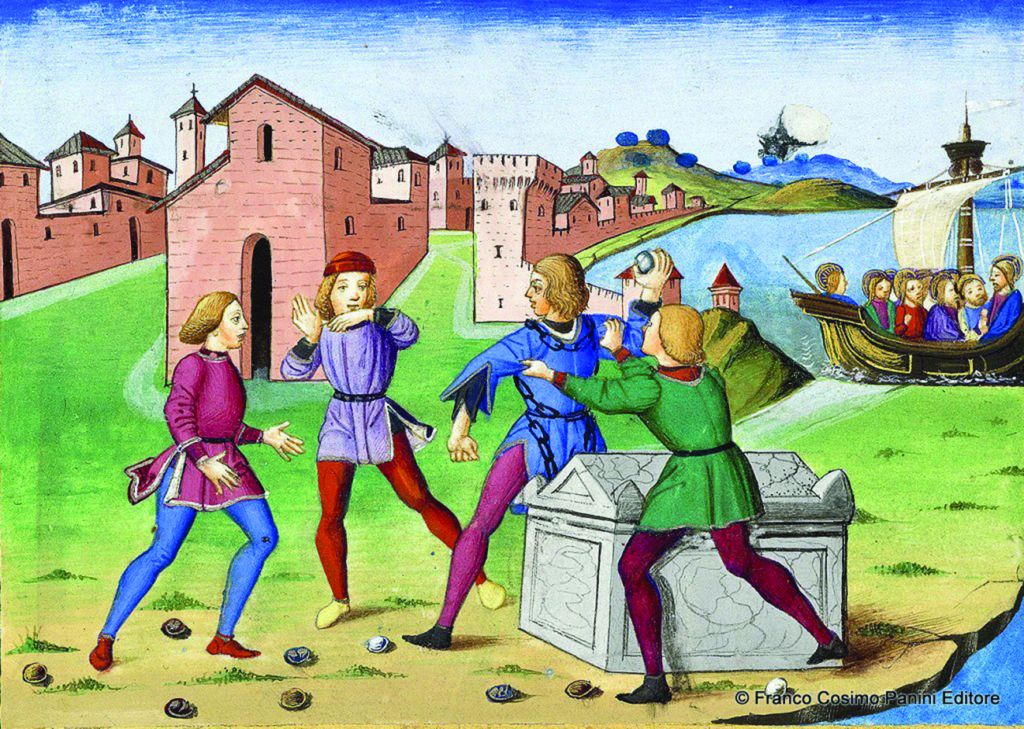

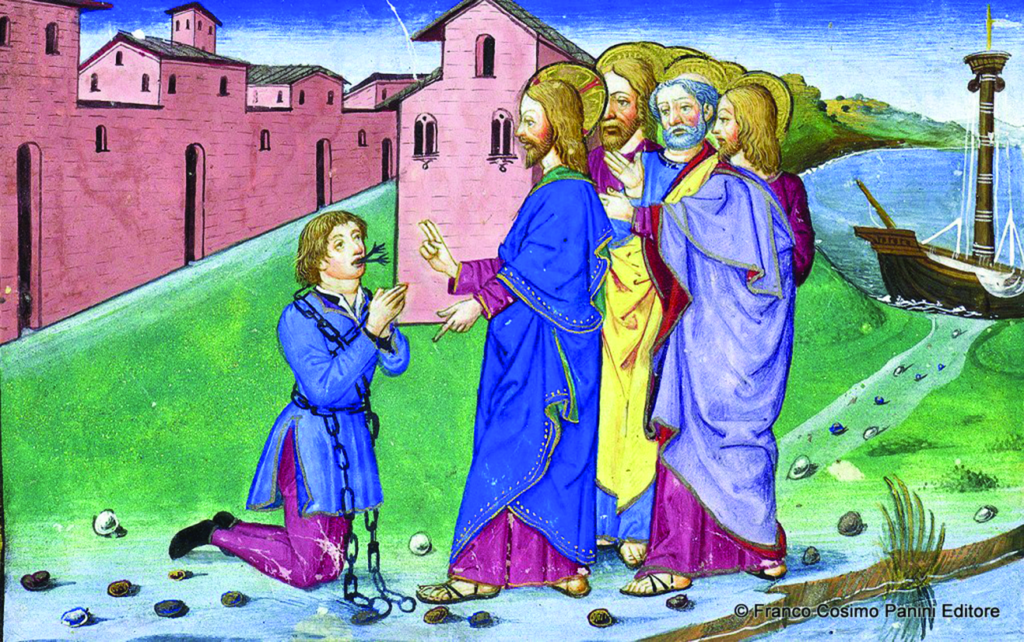

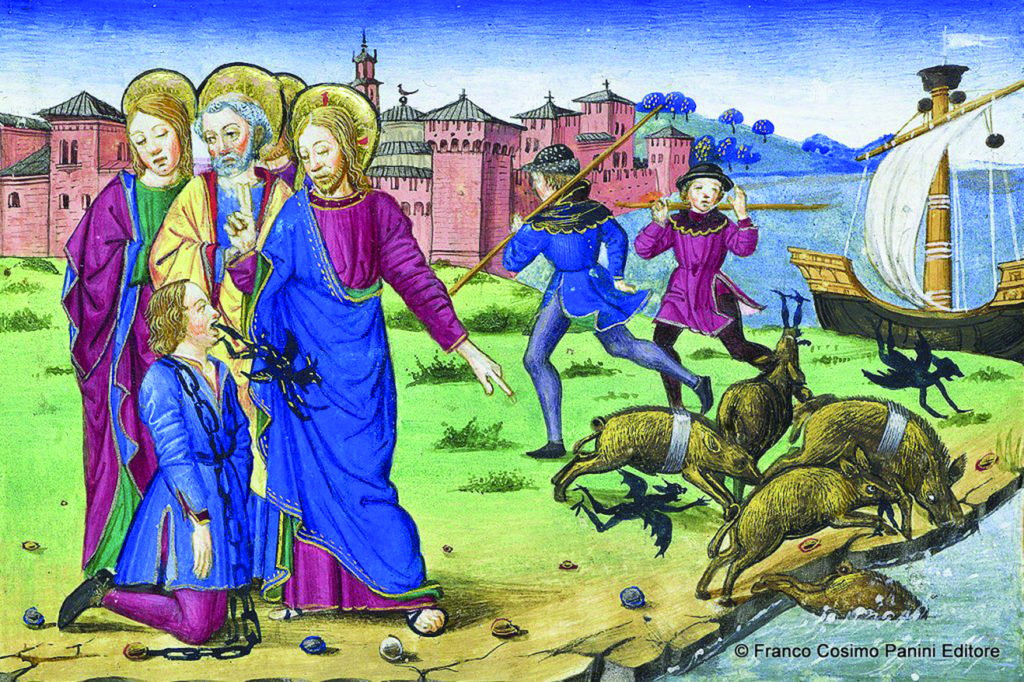

A series of scenes depicting the Gospel story in which Jesus restores to sound mind a demon-possessed man.

And behold, all the “ city came out to meet Jesus; and when they saw him, they begged him to leave their neighborhood” (Mt. 8:34).

A most mysterious verse, this. For the people had suffered much from the demoniacs Jesus had healed. You might think that the loss of a herd of swine, pitching themselves over the cliff into the sea when Jesus cast the demons into them, was a small price for the healing of two men, and the safety of that road along the shore, for the demoniacs were “so fierce, that no one could pass that way” (29).

And what were these people doing, herding swine? For Jews, those beasts were themselves unclean, like the spirits that had possessed the men, and like the tombs where they dwelt, full of corruption and dead men’s bones. The pagan Roman overlords, I imagine, liked pork roast well enough, and perhaps that explains the work, or perhaps the people of that region were not strict observers of the Mosaic law.

In any case, they ask Jesus to do just what the demons have asked. They ask him to get lost. Take then the words of the demons and imagine that people are saying them: “What have you to do with us, O Son of God? Have you come here to torment us before the time?”

When the people of the city came out, they saw Jesus with one of the men whom he had healed. The man was no longer naked, and no longer to be driven into the desert by the demon —and here I turn to the account in Luke (8:26-39). He was sitting at Jesus’ feet. Why did the people not rejoice?

Luke says that it was their fear. But what were they afraid of? The demons had gone down with the swine into the deep blue sea. The man — one of them, in any case — was “clothed and in his right mind.” The way was clear. What were they afraid of? The healing power of God?

Is that something to fear? Of course it is. The fear here, Greek phobos, does not suggest mere nervousness or sweaty anticipation. It suggests dread and awe, as when we read in Proverbs that the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom (9:10). But the dread the people here experience does not lead them to fall down in worship and gratitude. They know, somehow, that to welcome Jesus into their midst would be like admitting the presence of the divine into the light of their common day. And that is unendurable.

They walk, as do all men, on the verge of a precipice, even as they shut their eyes and pretend that it is not so. One false step, and perdition — but they do not welcome him who would open their eyes to their peril.

They dwell, as do all men, in tombs, that is, in a life that leads but to death and oblivion, playing with the common toys of mankind—gold, power, lust, fine clothing, wine, prestige, swine, dead men’s bones.

They are naked, too, because the clothing they wear serves only to reveal how bare and shivering their souls are; the clothing is a disguise to hide them from others and from themselves.

They throw rocks at each other and curse. Their hands are bloody, and they know not what they do.

We imagine that if we saw the face of Jesus, and if he worked a miracle in our presence, we would be so struck with wonder that our lives would never be the same again. Ah, but that is the point. Our lives would never be the same again.

It would mean a kind of death, and we are afraid to die, even if the way down into the valley of shadows, or the way up the bleak bald hill called Golgotha, leads to everlasting life.

We are afraid to die.

It is not the time, is it, for us to die? Must it be here, must it be now? Can we not go raging through the desert, naked and howling, one last frenzied time? Is there not a sick pleasure in self-torment, just as the demon-ridden man was “always crying out, and bruising himself with stones” (Mk. 5:5)?

“Why have you come to trouble us?” we ask of Jesus. “Leave us alone. We are doing fine without you. Go away.”

But there was one person who did not say that. It was one of the two men who had been healed.

For “the man from whom the demons had gone begged that he might be with [Jesus]” (Lk. 8:38). We are not told about the other. And here Jesus does something mysterious. He tells him to go home and tell everyone about the great thing God has done for him.

The evil spirits are cast into a herd of swine who dive into the Sea of Galilee. The miniatures are taken from a late medieval illustrated manuscript, the Legendary Sforza-Savoia (Milan, 1476), now in the Royal Library in Turin, Italy

If you want to read an excellent meditation upon what might well have happened then, go to Riccardo Bacchelli’s great novel, Lo Sguardo di Gesù — or The Gaze of Jesus, soon to appear in my English translation.

Bacchelli assumes that the man’s family and townsmen would be about as eager to welcome him as the swineherds and the people of that region were. That is a perfectly reasonable thing to assume. If the people who saw the miracle that Jesus wrought begged him to leave them in peace — at least in such peace as the world can know, the usual restlessness of human business and sin, the tense peace of night and locked doors — what about the people who did not see the miracle? They might well eye the healed man with suspicion. Who knows when the demon might rush into him again, and the madness resume? They had gotten used to doing without the man. Why should they now have to change their ways? Let him get lost then, too, or at least keep quiet about the healing. If it is bad to have a brother who was possessed by a demon and who did unspeakable deeds of darkness, it is almost as bad to have him around again in health to remind everyone of it all.

There is one last detail to the account that I wish to look at. When Jesus asks the demon its name, it replies, “My name is Legion; for we are many” (Mk. 5:9).

That’s a Roman word, the Latin to name the greatest of the divisions of the Roman army. Suppose it is not an exaggeration. Imagine, then, a legion of devils infesting the soul of a man—devils of all sorts, with all kinds of evil inclinations. The sheer horror of it boggles the mind. And yet — what else is the battlefield of the human soul, or of every human society that has existed on the face of the earth? The legionnaires of hell are in their panoply, and they often have a fine time of it, resting on their laurels.

“You’re here before your time,” says the world to Jesus. “Get lost, and take your shabby followers with you.”

It is the great gift of God that he does not do what we beg him to do.

Facebook Comments