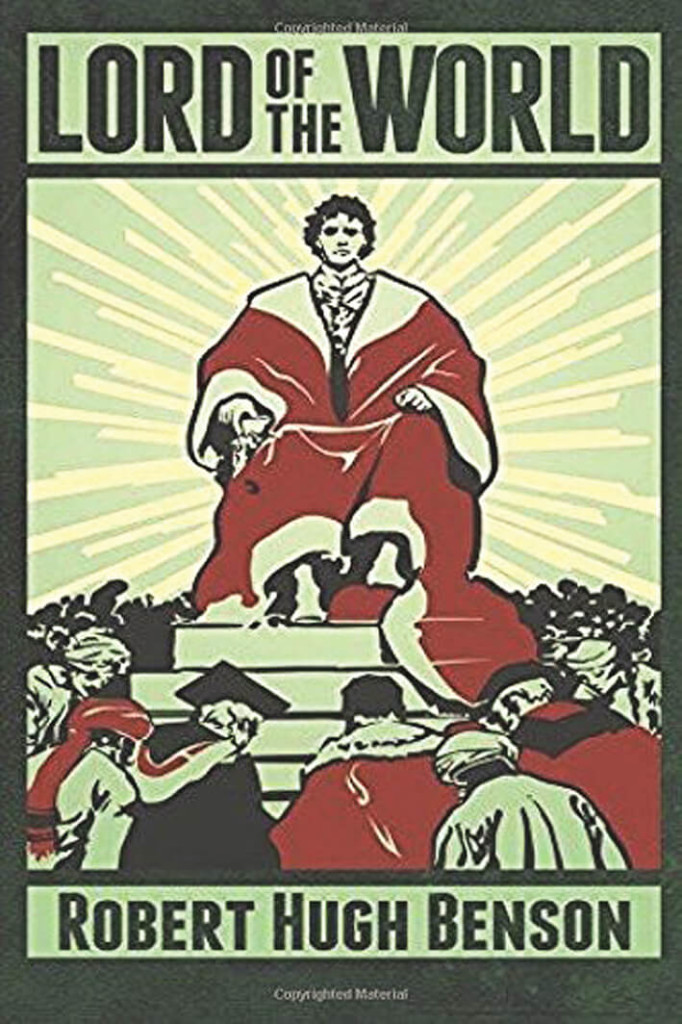

More than a century ago, Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson foresaw the rise of secular humanism, the contraction of the Catholic Church, and the coming of the Antichrist…

By ITV Staff

Editor’s Note: The passage below is from the novel Lord of the World, written by the English Catholic convert Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson (the son of the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury) in 1907. He attempts a vision of the world more than a century in the future — in the early 21st century… our own time… predicting the rise of Communism, the fall of faith in many places, the advance of technology (he foresees helicopters) and so forth, up until… the Second Coming of the Lord, with which his vision ends. For this reason, and also because Pope Benedict and Pope Francis have repeatedly cited Benson’s book, saying its clarification of the danger of a type of humanitarianism without God is a true danger that we do face, we are printing selections from it in ITV, now and in the months ahead.

Editor’s Note: The passage below is from the novel Lord of the World, written by the English Catholic convert Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson (the son of the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury) in 1907. He attempts a vision of the world more than a century in the future — in the early 21st century… our own time… predicting the rise of Communism, the fall of faith in many places, the advance of technology (he foresees helicopters) and so forth, up until… the Second Coming of the Lord, with which his vision ends. For this reason, and also because Pope Benedict and Pope Francis have repeatedly cited Benson’s book, saying its clarification of the danger of a type of humanitarianism without God is a true danger that we do face, we are printing selections from it in ITV, now and in the months ahead.

LORD OF THE WORLD

BY ROBERT HUGH BENSON (1907)

BOOK II-THE ENCOUNTER. CHAPTER III

(Note: The hero of the story, a young English priest named Fr. Percy Franklin, has come to Rome to report directly to the Pope on what he has seen in England: the emergence of a popular political figure who seems entirely humanistic, and so to have one of the characteristics of… the anti-Christ. Percy has just met the “Papa Angelicus” who is now 89, and has been Pope for nine years. Percy has briefed the Pope, and proposed to the Pope the creation of a new “Order of the Cross.“ Percy is now staying in Rome…)

His heart quickened as he saw it—as he swept his eyes round and across to the right and saw as in a mirror the replica of the left in the right transept. It was there then that they sat—those lonely survivors of that strange company of persons who, till half-a-century ago, had reigned as God’s temporal Vicegerents with the consent of their subjects. They were unrecognised, now, save by Him from whom they drew their sovereignty—pinnacles clustering and hanging from a dome, from which the walls had been withdrawn. These were men and women who had learned at last that power comes from above, and their title to rule came not from their subjects but from the Supreme Ruler of all—shepherds without sheep, captains without soldiers to command. It was piteous—horribly piteous, yet inspiring. The act of faith was so sublime; and Percy’s heart quickened as he understood it. These, then, men and women like himself, were not ashamed to appeal from man to God, to assume insignia which the world regarded as playthings, but which to them were emblems of supernatural commission. Was there not mirrored here, he asked himself, some far-off shadow of One Who rode on the colt of an ass amid the sneers of the great and the enthusiasm of children?…

*****

It was yet more kindling as the mass went on, and he saw the male sovereigns come down to do their services at the altar, and to go to and fro between it and the Throne. There they went bareheaded, the stately silent figures. The English king, once again Fidei Defensor, bore the train in place of the old king of Spain, who, with the Austrian Emperor, alone of all European sovereigns, had preserved the unbroken continuity of faith. The old man leaned over his fald-stool, mumbling and weeping, even crying out now and again in love and devotion, as, like Simeon, he saw his Salvation. The Austrian Emperor twice administered the Lavabo; the German sovereign, who had lost his throne and all but his life upon his conversion four years before, by a new privilege placed and withdrew the cushion, as his Lord kneeled before the Lord of them both.

So movement by movement the gorgeous drama was enacted; the murmuring of the crowds died to a stillness that was but one wordless prayer as the tiny White Disc rose between the white hands, and the thin angelic music pealed in the dome. For here was the one hope of these thousands, as mighty and as little as once within the Manger. There was none other that fought for them but only God. Surely then, if the blood of men and the tears of women could not avail to move the Judge and Observer of all from His silence, surely at least here the bloodless Death of His only Son, that once on Calvary had darkened heaven and rent the earth, pleaded now with such sorrowful splendour upon this island of faith amid a sea of laughter and hatred—this at least must avail! How could it not?

*****

Percy had just sat down, tired out with the long ceremonies, when the door opened abruptly, and the Cardinal, still in his robes, came in swiftly, shutting the door behind him.

“Father Franklin,” he said, in a strange breathless voice, “there is the worst of news. Felsenburgh is appointed President of Europe.”

II

It was late that night before Percy returned, completely exhausted by his labours. For hour after hour he had sat with the Cardinal, opening despatches that poured into the electric receivers from all over Europe, and were brought in one by one into the quiet sitting-room. Three times in the afternoon the Cardinal had been sent for, once by the Pope and twice to the Quirinal.

There was no doubt at all that the news was true; and it seemed that Felsenburgh must have waited deliberately for the offer. All others he had refused. There had been a Convention of the Powers, each of whom had been anxious to secure him, and each of whom had severally failed; these private claims had been withdrawn, and an united message sent. The new proposal was to the effect that Felsenburgh should assume a position hitherto undreamed of in democracy; that he should receive a House of Government in every capital of Europe; that his veto of any measure should be final for three years; that any measure he chose to introduce three times in three consecutive years should become law; that his title should be that of President of Europe. From his side practically nothing was asked, except that he should refuse any other official position offered him that did not receive the sanction of all the Powers. And all this, Percy saw very well, involved the danger of an united Europe increased tenfold. It involved all the stupendous force of Socialism directed by a brilliant individual. It was the combination of the strongest characteristics of the two methods of government. The offer had been accepted by Felsenburgh after eight hours’ silence.

It was remarkable, too, to observe how the news had been accepted by the two other divisions of the world. The East was enthusiastic; America was divided. But in any case America was powerless: the balance of the world was overwhelmingly against her.

Percy threw himself, as he was, on to his bed, and lay there with drumming pulses, closed eyes and a huge despair at his heart. The world indeed had risen like a giant over the horizons of Rome, and the holy city was no better now than a sand castle before a tide. So much he grasped. As to how ruin would come, in what form and from what direction, he neither knew nor cared. Only he knew now that it would come.

He had learned by now something of his own temperament; and he turned his eyes inwards to observe himself bitterly, as a doctor in mortal disease might with a dreadful complacency diagnose his own symptoms. It was even a relief to turn from the monstrous mechanism of the world to see in miniature one hopeless human heart. For his own religion he no longer feared; he knew, as absolutely as a man may know the colour of his eyes, that it was secure again and beyond shaking. During those weeks in Rome the cloudy deposit had run clear and the channel was once more visible. Or, better still, that vast erection of dogma, ceremony, custom and morals in which he had been educated, and on which he had looked all his life (as a man may stare upon some great set-piece that bewilders him), seeing now one spark of light, now another, flare and wane in the darkness, had little by little kindled and revealed itself in one stupendous blaze of divine fire that explains itself. Huge principles, once bewildering and even repellent, were again luminously self-evident; he saw, for example, that while Humanity-Religion endeavoured to abolish suffering the Divine Religion embraced it, so that the blind pangs even of beasts were within the Father’s Will and Scheme; or that while from one angle one colour only of the web of life was visible—material, or intellectual, or artistic—from another the Supernatural was as eminently obvious. Humanity-Religion could only be true if at least half of man’s nature, aspirations and sorrows were ignored. Christianity, on the other hand, at least included and accounted for these, even if it did not explain them. This … and this … and this … all made the one and perfect whole. There was the Catholic Faith, more certain to him than the existence of himself: it was true and alive. He might be damned, but God reigned. He might go mad, but Jesus Christ was Incarnate Deity, proving Himself so by death and Resurrection, and John his Vicar. These things were as the bones of the Universe—facts beyond doubting—if they were not true, nothing anywhere was anything but a dream.

Difficulties?—Why, there were ten thousand. He did not in the least understand why God had made the world as it was, nor how Hell could be the creation of Love, nor how bread was transubstantiated into the Body of God but—well, these things were so.

He had travelled far, he began to see, from his old status of faith, when he had believed that divine truth could be demonstrated on intellectual grounds. He had learned now (he knew not how) that the supernatural cried to the supernatural; the Christ without to the Christ within; that pure human reason indeed could not contradict, yet neither could it adequately prove the mysteries of faith, except on premisses visible only to him who receives Revelation as a fact; that it is the moral state, rather than the intellectual, to which the Spirit of God speaks with the greater certitude.

That which he had both learned and taught he now knew, that Faith, having, like man himself, a body and a spirit—an historical expression and an inner verity—speaks now by one, now by another. This man believes because he sees—accepts the Incarnation or the Church from its credentials; that man, perceiving that these things are spiritual facts, yields himself wholly to the message and authority of her who alone professes them, as well as to the manifestation of them upon the historical plane; and in the darkness leans upon her arm. Or, best of all, because he has believed, now he sees. So he looked with a kind of interested indolence at other tracts of his nature.

First, there was his intellect, puzzled beyond description, demanding, Why, why, why? Why was it allowed? How was it conceivable that God did not intervene, and that the Father of men could permit His dear world to be so ranged against Him? What did He mean to do? Was this eternal silence never to be broken?

It was very well for those that had the Faith, but what of the countless millions who were settling down in contented blasphemy? Were these not, too, His children and the sheep of His pasture? What was the Catholic Church made for if not to convert the world, and why then had Almighty God allowed it, on the one side, to dwindle to a handful, and, on the other, the world to find its peace apart from Him?

(To be continued)

Facebook Comments