By Lucy Gordan

Santa Maria dell’Anima (St. Mary of the Soul), located close to Piazza Navona. In contrast with the austerity of the church’s exterior, its interior is lavishly decorated with brightly colored frescoes, paintings, and sculptures, including Baldassare Peruzzi’s funerary monument for the gloomy Dutch Pope Adrian VI

Many countries have national churches in Rome: Albania, Argentina, Canada, Croatia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Greece, Hungary, Japan, Lebanon, Mexico, Netherlands, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Scotland, Sweden, and the United States. The Ukraine and Spain each have two; Armenia has three; and France has four. Ethiopia has one in Vatican City, and Germany has one in Rome and one in Vatican City. Both German shrines began as hospices, date to the Middle Ages, and are dedicated to the Virgin.

Santa Maria dell’Anima (St. Mary, or Our Lady, of the Soul), located close to Piazza Navona, is one of the many medieval charity institutions first built as hospices for pilgrims visiting Rome. It was founded in 1350, when Johannes (Jan), either a Dutch merchant or an officer in the Papal Guard, and his wife Katharina Peters of Dordrecht, bought three houses and turned them into a private hospice for Dutch, Flemish, and German pilgrims during the 1350 Jubilee.

They named the hospice Hospitium Beatae Mariae Animarum (“Hospice of Blessed Mary of the Souls”) from an ancient fresco of the Virgin between two souls in Purgatory.

The first church, named Santa Maria dell’Anima, was built in 1431 on the site of the hospice’s chapel and consecrated by Pope Eugene IV in 1444. Soon afterwards the church’s Confraternity decided to build a new church on the same site for the Jubilee of 1500. Paid for by German subscriptions between 1499 and 1522 and a generous contribution by Johann Burchard of Strasbourg (c.1450-1506), papal Master of Ceremonies for Pope Alexander VI Borgia (r. 1492-1503), the “new” Church of Santa Maria dell’Anima, still standing today, wasn’t consecrated until November 25, 1542. Built in the style of a hallenkirchen or hall church, typical of Northern Europe, its architect was Andrea Sansovino, and Giuliano da Sangallo completed its plain Romanesque façade. It became the “national” church in Rome of the Holy Roman Empire and so the “national church and hospice” of German-speaking people in Rome.

In contrast with the austerity of the church’s exterior, its interior is lavishly decorated with brightly-colored frescoes (for example, the Life of the Virgin by Girolamo Siciolante da Sermoneta) and paintings: St. Bennone’s Miracles (1618), by Caravaggio’s heir Carlo Saraceni, and the altarpiece of the Holy Family (damaged by floodwaters from the Tiber) by Raphael’s talented collaborator Giulio Romano, a Pietà by Lorenzetto, and Baldassare Peruzzi’s funerary monument for the gloomy Dutch Pope Adrian VI (r. 1522-3), the last non-Italian pope before John Paul II. He’d been buried in St. Peter’s until Cardinal William of Enckenvoirt (1464-1544), later also buried there, transferred his remains here.

Views of the Vatican’s Teutonic cemetery from above (from the roof of St. Peter’s Basilica) and inside

To return to Burchard, he not only helped to finance the “new” church in 1496, but, as provost of the Confraternity of Santa Maria dell’Anima, he turned the hospice into a residential college for priests who studied (and still do) at one of the Pontifical Atheneums for advanced studies or who work in the Curia. Known as the Pontifical Teutonic College Santa Maria dell’Anima, for many centuries these students came from the many countries of the Holy Roman Empire, not exclusively from Germany. The College served and still does as an intermediary between Austrian and German dioceses and the Curia and as a residence in Rome for German and Austrian bishops and priests as well as their citizens in difficulty.

Not surprisingly, during the Napoleonic occupation the church was plundered and its sacristy used as a stable. Luckily, in 1859 the College was reestablished, but this time for chaplains who remained in residence for two or at most three years to study canon law, with a view to using this newly-acquired knowledge in their dioceses or universities back home. Nonetheless, the College continued to assist Germans who fell on hard times while in Rome.

The Napoleonic occupation was not the only time the church and College had connections to hostilities. In 1937 a chapel was built in commemoration of the Austro-Hungarian First World War soldiers. Underneath it are buried about 450 soldiers, mostly still unidentified, who’d died in POW camps near Rome. A project, started in 2021 and supported by the Austrian Ministry of Defense, aims to identify them.

Also on the dark side, after World War II, the College served as a “Ratline” to help Nazi War criminals, for example Gustav Wagner and Franz Stangl, escape to Brazil.

Another College-connected episode, this time ironic, is that, according to its then-custodian, during the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) Joseph Ratzinger, then a young priest, who attended all four sessions of the Council as a peritus or expert for Cardinal Joseph Frings, the Archbishop of Cologne, was turned away from the College due to no vacancy. Luckily, instead, he found lodging at a temporary residence for priests just across the street!

As I mentioned before, the German College downtown has a twin in Vatican City founded 50 years before. Besides being a hospice for German-speaking pilgrims, the guilds of German bakers, weavers, and cobblers had their headquarters here. In 1876 the hospice also took in for 2-year residencies priests from the Austro-Hungarian Empire who were pursuing their studies and officiating at Mass in the nearby Church of Santa Maria della Pietà (Our Lady of Mercy).

Father Hugh O’Flaherty

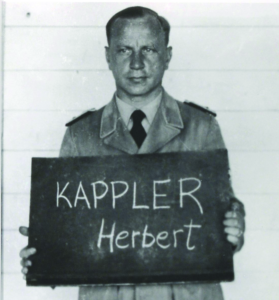

Herbert Kappler on his arrest

Surprisingly, however, the College’s most special resident was not German, but an Irish priest, Hugh O’Flaherty (1898-1963). He’d served as a Vatican diplomat in Egypt, Haiti, Santo Domingo, and Czechoslovakia, and lived here while working for the Sacred Congregation De Propaganda Fide. From his bedroom he clandestinely established the “Rome Escape Line,” a precious network of assistants with whom he saved some 6,500 conscientious objectors, Allied soldiers including escaped POWs, and Jews. O’Flaherty’s team lodged them in Vatican extraterritorial residences and religious institutes during the Nazi occupation of Rome. Nicknamed “The Scarlet Pimpernel of the Vatican,” evading traps set by the Gestapo and Sicherheitsdienst (SD) who wanted to assassinate him, O’Flaherty met his contacts on the steps of St. Peter’s. Since the Nazis couldn’t arrest him inside the Vatican, the infuriated Obersturmbannführer Herbert Kappler ordered a white line painted on the pavement at the opening of St. Peter’s Square (the border between Vatican City and Italy). He stated that the priest would be first tortured and then killed if he crossed the line, which is still there today. Ironically, after the War, O’Flaherty, Kappler’s only permitted visitor, regularly comforted his former nemesis in prison. In 1959, Kappler converted to Catholicism and O’Flaherty baptized him.

In addition to providing housing, the Vatican’s College has a library specializing in Christian archeology and an important collection of early Christian art.

A few years ago Pope Benedict XVI spoke of his intention to bequeath his personal library of some 5,000 liturgical and theological volumes, as well as his collection of musical scores, here. In 1888 the Roman Institute of the Görres Society (Görresgesellschaft) was established in the College and together they still publish a quarterly review, the Römische Quartalschrift für christliche Archäologie und Kirchengeschichte.

The year before he was crowned in St. Peter’s on Christmas Day 800, Charlemagne established the Vatican’s German Shrine on land granted to him by Pope Leo III (r. 795816) to build a hospice (the College), a church, Our Lady of Mercy, and a cemetery for German and Flemish pilgrims who’d died in Rome.

According to tradition, the cemetery, the only one in Vatican City, is located in Nero’s Circus, at the site of St. Peter’s crucifixion, its soil having been brought to Rome by St. Helena, the Emperor Constantine’s mother.

Still today the cemetery is for German and Flemish-speaking pilgrims who die in Rome, Confraternity members whose duty it is to maintain the cemetery, German and Flemish priests and nuns, and German-speaking civilians who have served the Church. No one knows how many people have been buried here over the centuries, though some sources say around 1,500. The earliest gravestone dates to 1474, and one of the most recent graves belongs to a homeless Belgian, Willy Herteleer, who died on December 12, 2015.

Had he not been elected Pope, Cardinal Ratzinger’s would probably have been the most recent grave. After his appointment as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Ratzinger celebrated Mass every Thursday (some sources say every day) at 7 AM in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel, one of the two chapels in Our Lady of Mercy. The other chapel is the burial place of the 190 Swiss Guards who died making their last stand in the Teutonic Cemetery during the Sack of Rome on May 6, 1527. Technically-speaking, this church is in Italy, not in Vatican City, but, since it can only be accessed from inside the Vatican via the cemetery, it’s governed by the 1929 Lateran Pact, giving it extraterritorial status.

The Vatican’s Teutonic Shrine is open daily from 7 AM to noon. Visitors must request permission from the Swiss Guards stationed at the large white gate near the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in the Palazzo del Sant’ Uffizio. The same entrance gate leads to the Paul VI Audience Hall, outside Bernini’s colonnade, to the left of St. Peter’s Basilica.

For a detailed history of these two German shrines in Rome, click on www.romanchurchesfandom.com/wiki/Santa_Maria_della_Pietà.

Facebook Comments