More than a century ago, Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson foresaw the rise of secular humanism, the contraction of the Catholic Church, and the coming of the Antichrist…

By ITV Staff

Editor’s Note: The passage below is from the novel Lord of the World, written by the English Catholic convert Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson (the son of the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury) in 1907. He attempts a vision of the world more than a century in the future — in the early 21st century… our own time… predicting the rise of Communism, the fall of faith in many places, the advance of technology (he foresees helicopters) and so forth, up until… the Second Coming of the Lord, with which his vision ends. For this reason, and also because Pope Benedict and Pope Francis have repeatedly cited Benson’s book, saying its clarification of the danger of a type of humanitarianism without God is a true danger that we do face, we are printing selections from it in ITV, now and in the months ahead.

Editor’s Note: The passage below is from the novel Lord of the World, written by the English Catholic convert Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson (the son of the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury) in 1907. He attempts a vision of the world more than a century in the future — in the early 21st century… our own time… predicting the rise of Communism, the fall of faith in many places, the advance of technology (he foresees helicopters) and so forth, up until… the Second Coming of the Lord, with which his vision ends. For this reason, and also because Pope Benedict and Pope Francis have repeatedly cited Benson’s book, saying its clarification of the danger of a type of humanitarianism without God is a true danger that we do face, we are printing selections from it in ITV, now and in the months ahead.

Lord of the World

By Robert Hugh Benson (1907)

Book II: The Encounter, Chapter II, Part IV, Section II

(Note: The hero of the story, a young English priest named Fr. Percy Franklin, has just gone to Rome to report directly to the Pope on what he has seen in England: the emergence of a popular political figure who seems to be entirely humanistic, and so to have one of the characteristics of the anti-Christ. Now the scene shifts back to England, where this new political figure is about to enter Parliament and call for a new humanistic religion…)

Section II

Mabel, seated in the gallery that evening behind the President’s chair, had already glanced at her watch half-a-dozen times in the last hour, hoping each time that twenty-one o’clock was nearer than she feared. She knew well enough by now that the President of Europe would not be half-a-minute either before or after his time. His supreme punctuality was famous all over the continent. He had said Twenty-One, so it was to be twenty-one. A sharp bell-note impinged from beneath, and in a moment the drawling voice of the speaker stopped. Once more she lifted her wrist, saw that it wanted five minutes of the hour; then she leaned forward from her corner and stared down into the House.

A great change had passed over it at the metallic noise. All down the long brown seats members were shifting and arranging themselves more decorously, uncrossing their legs, slipping their hats beneath the leather fringes. As she looked, too, she saw the President of the House coming down the three steps from his chair, for Another would need it in a few moments.

The house was full from end to end; a late comer ran in from the twilight of the south door and looked distractedly about him in the full light before he saw his vacant place. The galleries at the lower end were occupied too, down there, where she had failed to obtain a seat. Yet from all the crowded interior there was no sound but a sibilant whispering; from the passages behind she could hear again the quick bell-note repeat itself as the lobbies were cleared; and from Parliament Square outside once more came the heavy murmur of the crowd that had been inaudible for the last twenty minutes. When that ceased she would know that he was come.

How strange and wonderful it was to be here—on this night of all, when the President was to speak! A month ago he had assented to a similar Bill in Germany, and had delivered a speech on the same subject at Turin. To-morrow he was to be in Spain.

No one knew where he had been during the past week. A rumour had spread that his volor had been seen passing over Lake Como, and had been instantly contradicted. No one knew either what he would say to-night. It might be three words or twenty thousand.

There were a few clauses in the Bill—notably those bearing on the point as to when the new worship was to be made compulsory on all subjects over the age of seven—it might be he would object and veto these. In that case all must be done again, and the Bill repassed, unless the House accepted his amendment instantly by acclamation.

Mabel herself was inclined to these clauses. They provided that, although worship was to be offered in every parish church of England on the ensuing first day of October, this was not to be compulsory on all subjects till the New Year; whereas, Germany, who had passed the Bill only a month before, had caused it to come into full force immediately, thus compelling all her Catholic subjects either to leave the country without delay or suffer the penalties.

These penalties were not vindictive: on a first offence a week’s detention only was to be given; on the second, one month’s imprisonment; on the third, one year’s; and on the fourth, perpetual imprisonment until the criminal yielded.

These were merciful terms, it seemed; for even imprisonment itself meant no more than reasonable confinement and employment on Government works. There were no mediaeval horrors here; and the act of worship demanded was so little, too; it consisted of no more than bodily presence in the church or cathedral on the four new festivals of Maternity, Life, Sustenance and Paternity, celebrated on the first day of each quarter. Sunday worship was to be purely voluntary.

She could not understand how any man could refuse this homage. These four things were facts—they were the manifestations of what she called the Spirit of the World—and if others called that Power God, yet surely these ought to be considered as His functions. Where then was the difficulty? It was not as if Christian worship were not permitted, under the usual regulations. Catholics could still go to Mass. And yet appalling things were threatened in Germany: not less than 12,000 persons had already left for Rome; and it was rumoured that 40,000 would refuse this simple act of homage a few days hence. It bewildered and angered her to think of it.

For herself the new worship was a crowning sign of the triumph of Humanity. Her heart had yearned for some such thing as this— some public corporate profession of what all now believed. She had so resented the dulness of folk who were content with action and never considered its springs. Surely this instinct within her was a true one; she desired to stand with her fellows in some solemn place, consecrated not by priests but by the will of man; to have as her inspirers sweet singing and the peal of organs; to utter her sorrow with thousands beside her at her own feebleness of immolation before the Spirit of all; to sing aloud her praise of the glory of life, and to offer by sacrifice and incense an emblematic homage to That from which she drew her being, and to whom one day she must render it again. Ah! these Christians had understood human nature, she had told herself a hundred times: it was true that they had degraded it, darkened light, poisoned thought, misinterpreted instinct; but they had understood that man must worship — must worship or sink.

For herself she intended to go at least once a week to the little old church half-a-mile away from her home, to kneel there before the sunlit sanctuary, to meditate on sweet mysteries, to present herself to That which she was yearning to love, and to drink, it might be, new draughts of life and power.

Ah! but the Bill must pass first…. She clenched her hands on the rail, and stared steadily before her on the ranks of heads, the open gangways, the great mace on the table, and heard, above the murmur of the crowd outside and the dying whispers within, her own heart beat.

She could not see Him, she knew. He would come in from beneath through the door that none but He might use, straight into the seat beneath the canopy. But she would hear His voice—that must be joy enough for her….

Ah! there was silence now outside; the soft roar had died. He had come then. And through swimming eyes she saw the long ridges of heads rise beneath her, and through drumming ears heard the murmur of many feet. All faces looked this way; and she watched them as a mirror to see the reflected light of His presence. There was a gentle sobbing somewhere in the air—was it her own or another’s? … the click of a door; a great mellow booming overhead, shock after shock, as the huge tenor bells tolled their three strokes; and, in an instant, over the white faces passed a ripple, as if some breeze of passion shook the souls within; there was a swaying here and there; and a passionless voice spoke half a dozen words in Esperanto, out of sight: “Englishmen, I assent to the Bill of Worship.”

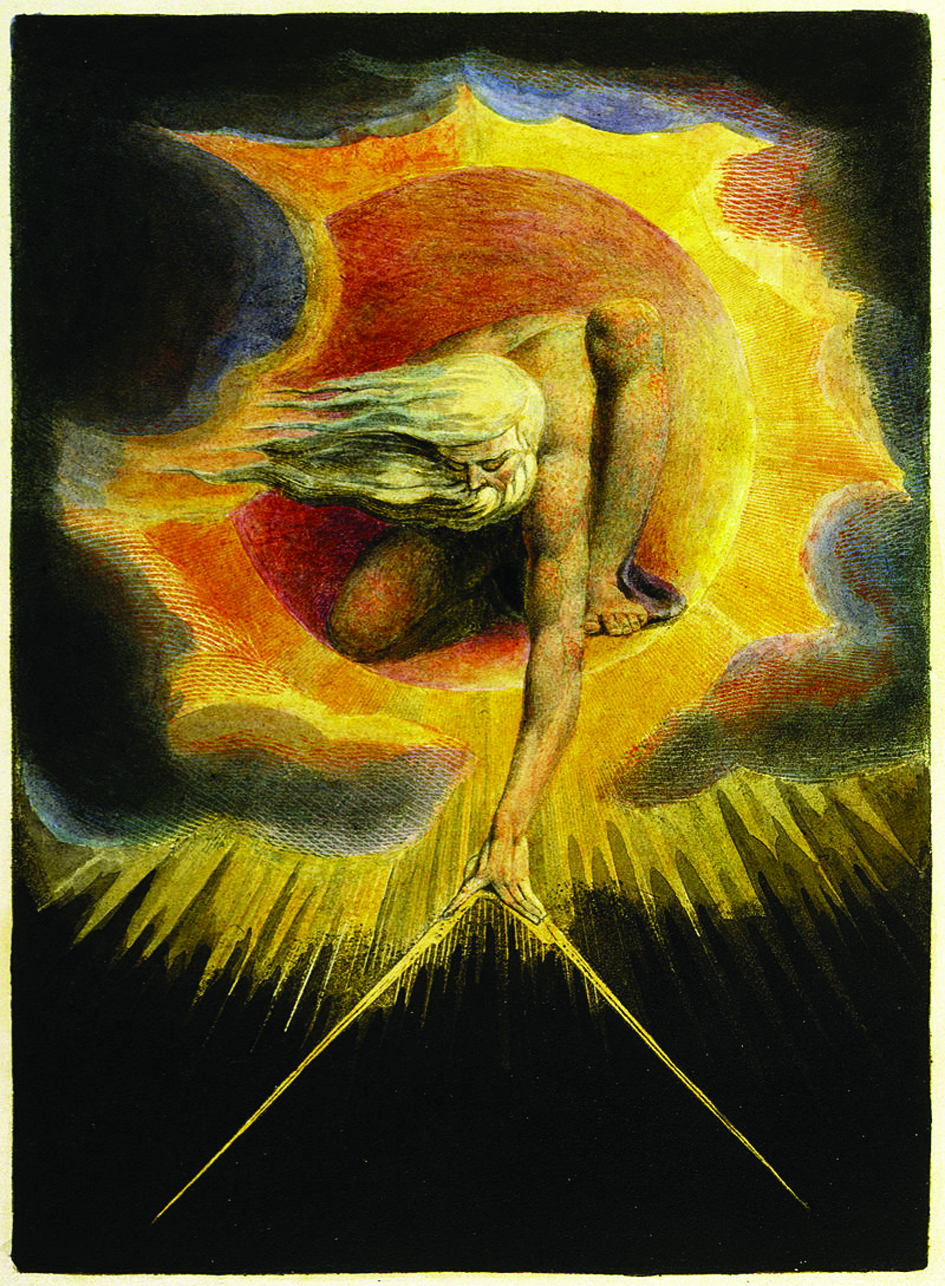

God as seen by William Blake as the Architect of the world, in Ancient of Days, held in the British Museum, London

III

It was not until mid-day breakfast on the following morning that husband and wife met again. Oliver had slept in town and telephoned about eleven o’clock that he would be home immediately, bringing a guest with him: and shortly before noon she heard their voices in the hall. Mr. Francis, who was presently introduced to her, seemed a harmless kind of man, she thought, not interesting, though he seemed in earnest about this Bill. It was not until breakfast was nearly over that she understood who he was.

“Don’t go, Mabel,” said her husband, as she made a movement to rise. “You will like to hear about this, I expect. My wife knows all that I know,” he added.

Mr. Francis smiled and bowed.

“I may tell her about you, sir?” said Oliver again.

“Why, certainly.”

Then she heard that he had been a Catholic priest a few months before, and that Mr. Snowford was in consultation with him as to the ceremonies in the Abbey. She was conscious of a sudden interest as she heard this.

“Oh! do talk,” she said. “I want to hear everything.”

It seemed that Mr. Francis had seen the new Minister of Public Worship that morning, and had received a definite commission from him to take charge of the ceremonies on the first of October. Two dozen of his colleagues, too, were to be enrolled among the ceremoniarii, at least temporarily—and after the event they were to be sent on a lecturing tour to organise the national worship throughout the country.

Of course things would be somewhat sloppy at first, said Mr. Francis; but by the New Year it was hoped that all would be in order, at least in the cathedrals and principal towns.

“It is important,” he said, “that this should be done as soon as possible. It is very necessary to make a good impression. There are thousands who have the instinct of worship, without knowing how to satisfy it.”

“That is perfectly true,” said Oliver. “I have felt that for a long time. I suppose it is the deepest instinct in man.”

“As to the ceremonies—” went on the other, with a slightly important air. His eyes roved round a moment; then he dived into his breast-pocket, and drew out a thin red-covered book.

“Here is the Order of Worship for the Feast of Paternity,” he said. “I have had it interleaved, and have made a few notes.”

He began to turn the pages, and Mabel, with considerable excitement, drew her chair a little closer to listen.

“That is right, sir,” said the other. “Now give us a little lecture.”

Mr. Francis closed the book on his finger, pushed his plate aside, and began to discourse… (To be continued)

Facebook Comments