His outstretched finger points to something—Someone—other than himself

By John Byron Kuhner

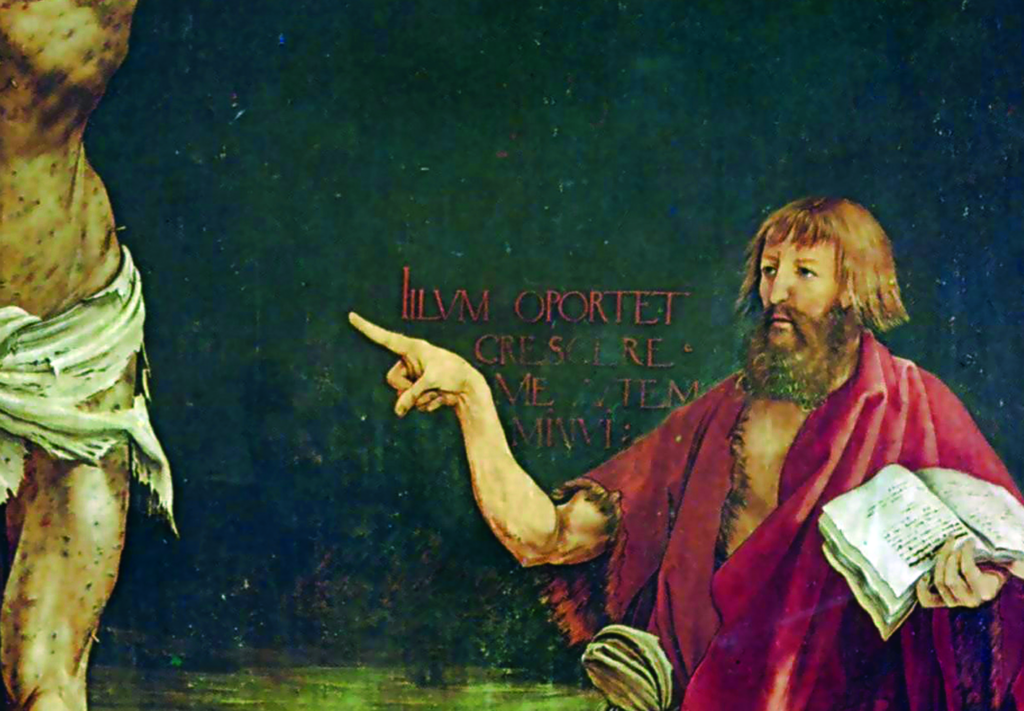

St. John the Baptist Announces the Coming of Christ by Mattia Preti (c. 1665)

I once had the misfortune of touring the Uffizi Galleries in Florence in the company of a renowned professor of art history. Art history professors are of course notorious for not knowing anything about Christianity, even if Christian art is their field. This professor was an expert in the Renaissance. She brought the tour group to a painting of St. John the Baptist. “Florentine painters always show John the Baptist with his finger outstretched,” she intoned in her nasal British accent. “Does anyone know why?” She didn’t wait for an answer. “It’s because the finger of John the Baptist was in Florence! So when you see a Florentine painting of John the Baptist, they’re showing you the finger of John, as a way of saying, ‘Look how important Florence is.’ Isn’t that interesting? Most people don’t even know that.”

Needless to say, this is not the reason you see images of St. John pointing. The Florentines were undoubtedly proud of having the great saint’s index finger in their baptistry (you can visit it there today), and it remains an object of pilgrimage for those who know about it, but painters from every city in Christendom paint St. John with his finger outstretched.

To understand why, you’ll need to know your Bible — not, of course, a requirement for an art history degree.

Luckily, the painters often label their paintings with the relevant Biblical verses, usually in Greek or Latin (also not required for an art history degree). John is usually the most recognizable of all saints: shaggy hair and beard, shaggy clothing, and raised finger; but if those indicators fail, he often has a banner, or nearby motto: ECCE AGNUS DEI. “Behold, the Lamb of God.”

Some painters give the full version: ECCE AGNUS DEI, QUI TOLLIT PECCATA MUNDI. “Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.” Those who are not familiar with Latin will note that the language lacks a word for “of”: to say “of God” you change the ending of deus to dei. Mundus follows the same pattern, becoming mundi. This is called the genitive case, and dei and mundi are arguably the two most common genitives in Church usage (Ecclesia Dei, Lux Mundi, etc.) though Christi and Domini are two other common ones.

Ecce Agnus Dei qui tollit peccata mundi are the words of St. John the Baptist when he sees Christ, from the first chapter of the Gospel of John. They are used in the Mass as well, making the priest, when he shows the Most Sacred Body and Most Precious Blood to the congregation, a kind of figure of St. John the Baptist, “not the light, but here to give testimony to the light” (non erat ille lux, sed ut testimonium perhiberet de lumine).

Sometimes all that is written next to St. John is Ecce — a kind of synopsis of the role of all the saints in salvation: to say “Look!” Look at God. Don’t look at me here — look over there. John’s clothing and personal humility suggest the same — “I am not the mystery, the mystery is elsewhere” — but the ultimate incarnation of this idea is John’s finger.

The finger cannot only be something, but also means something. The point is not the finger, but what the finger indicates. The Latin word for the pointer finger is index, by the way; indicis in the genitive case, and the infinitive verb for “to point with the finger” is indicare.

St. John’s feast day and birthday is June 24. This is in keeping with Luke’s indication that St. John’s mother Elizabeth was “in the sixth month” when Jesus was conceived; so St. John is about six months older than Jesus is. This is another interesting example of meaning and significance, here applied to the year itself. Since the two were born six months apart, they stand on opposite sides of the year, and as we start to move away from one, we begin to head toward the other. St. Augustine noted this: “Christ was born when the days were beginning to increase; John was born when the days were beginning to diminish” (natus est Christus cum iam inciperent crescere dies, natus est Ioannes quando coeperunt minui dies).

St. John with the motto: Illum oportet crescere, me autem minui in a detail of the crucifixion by Matthias Grünewald in a panel of the Isenheim Altar preserved in the Musée d’Unterlinden in Colmar

This is a kind of astronomical example of the other motto you often see written by St. John: Illum oportet crescere, me autem minui. “He ought to increase, but I ought to decrease.”

John had said this describing his entire relationship with Christ (in Chapter Three of John’s Gospel, well worth reading in full). Hence, in honoring St. John on this day in June, the tradition suggests that even the furthest point in the year from Christmas points back towards it — indeed all Creation, rightly understood, says “Ecce!” and points to God.

It is said that understanding significance is one of the signs of intelligence in animals.

If you point at something, a rabbit will look at your finger; but a dog will look in the direction your finger indicates, and can understand that the finger means what it points towards.

It seems God sometimes reveals this truth to the lowly and humble, but has concealed it from the wise professors.

Facebook Comments