Fr. Titus Brandsma, outspoken critic of Nazism, was killed by a lethal injection—and he converted the nurse who administered it

By Andrew Rabel

Titus Brandsma, a Dutch Carmelite, journalist and manager of the Catholic press at the time of the Nazi occupation, canonized at St. Peter’s during the ceremony on May 15, presided over by Pope Francis. (Grzegorz Galazka photo)

On May 15, 2022, Pope Francis conducted 10 canonizations in Rome, in the presence of 50,000 persons. Several of these had been postponed because of the Covid outbreak in Italy. Pope Francis said, “It is good to see that, through their evangelical witness, these Saints have fostered the spiritual and social growth of their respective nations and also of the entire human family.”

One of these was Dutch Carmelite friar, Fr. Titus Brandsma O.Carm., who was killed by a lethal injection in Dachau concentration camp during World War II.

Anno Sjoerd Brandsma was born in Friesland in the north of the Netherlands on February 23, 1881. His family were dairy farmers. They were part of the small Catholic minority in the region. The family spoke Frisian rather than Dutch, and they were markedly religious in that five of the six Brandsma children pursued religious vocations. At the age of 11, Anno went to Franciscan minor seminary in the more Catholic South, following which he joined the Carmelite Order.

Following ordination to the priesthood, he pursued further studies in philosophy at the Gregorian University in Rome, gaining a doctorate. He returned to the Netherlands to teach philosophy and do research and write. He translated the works of St. Teresa of Avila into Dutch and worked on the medieval Dutch and Flemish mystics. From 1922, he was professor of philosophy and mystical theology in the new Catholic University of Nijmegen. He was active in the Catholic press. In 1935, he came to Ireland to study English in preparation for a lecture tour of the US, and he spent time in Kinsale in County Cork and at the Carmelite church on Whitefriars St. in Dublin, the capital — home to the shrine of Our Lady of Dublin and the relics of St. Valentine.

In the US, visiting Niagara Falls, one of the seven wonders of the world, he commented, “I not only see the riches of the nature of the water, its immeasurable potentiality; I see God working in the work of His hands and the manifestation of His love.”

In that same year, he became secretary of the Catholic Journalists’ Association in the Netherlands.

He was watching events in Germany at the time with horror as he opposed Nazism on ideological grounds. In 1940, the Netherlands was overrun by the Wehrmacht in five days.

The Dutch bishops took a robust anti-Nazi stance, excommunicating Catholics who joined the Dutch Nazi NSB. Fr. Brandsma acted as a point man between the Archbishop of Utrecht, Johannes de Jong (later a Cardinal) and the Catholic press. He was very firm that Catholic editors not publish Nazi propaganda.

The Reichskommisar, Dr Arthur Syess-Inquart, described Fr. Brandsma as a very dangerous man. He was arrested in early 1942 and spent time in various Dutch and German prisons before going to Dachau in June, often referred to as “the priest cemetery.” In his imprisonment, he was known for showing Christian charity even to the most brutal SS guards and the Kapos, with some effect. His health was never good and it was clear he wouldn’t last long in Dachau; while he was there, he was the victim of some medical experiments. After a month, the doctors ordered his death by lethal injection on July 26, 1942. He had already made an impression on the nurse who had to carry this out, and she soon returned to the faith and testified to his sanctity.

In 1957, the nurse, known pseudonymously as “Tizia,” testified: “I bear witness because of personal knowledge. I was in Dachau from April till October, 1942. There I got to know Fr. Titus a week before his death. I was a nurse in the infirmary of the concentration camp at Dachau. I visited him twice a day. Fourteen or 15 times I spoke with him briefly, about 10 minutes each time.

“When I was 16 years old I went to Berlin as a nurse for the Red Cross. There we had to swear an oath that we viewed Hitler as our god and we had to confirm that we would never go to church. The church and all else was only deceit. The Jews would have to be completely exterminated. That was the start of our training. I was too young to understand the consequences of all this.

“He (Titus) would have to die, irrespective of the fact that he would have arrived from Holland in good health, because they had a great deal of hatred towards distinguished clergy. When he arrived at the infirmary, he was already a candidate for death. That stems from the fact that the doctor had pointed him out as one of those who, after a certain period of time, would be administered the ‘Mercy-Injection.’ I sensed immediately that he felt very sorry for me. He was very gentle because he was aware that we, the doctor and I, had life and death at our disposal.

“A great majority of the ill prisoners were only concerned about themselves and only thought about themselves, but Titus was always in a good frame of mind and was a support for everyone and, in a special way, for me.”

Once, Fr. Brandsma gave her a wooden rosary, even though she was an atheist who openly “despised priests.” Not knowing what to do with the object, she kept it in her apron pocket. On the day when she injected Brandsma with the liquid that would end his life, she felt nervous and irritated. Some time later, she was moved when she found that rosary again. In her testimony, Tizia attributes to Fr. Brandsma her abandonment of the Nazi ideology and her conversion to the Catholic faith.

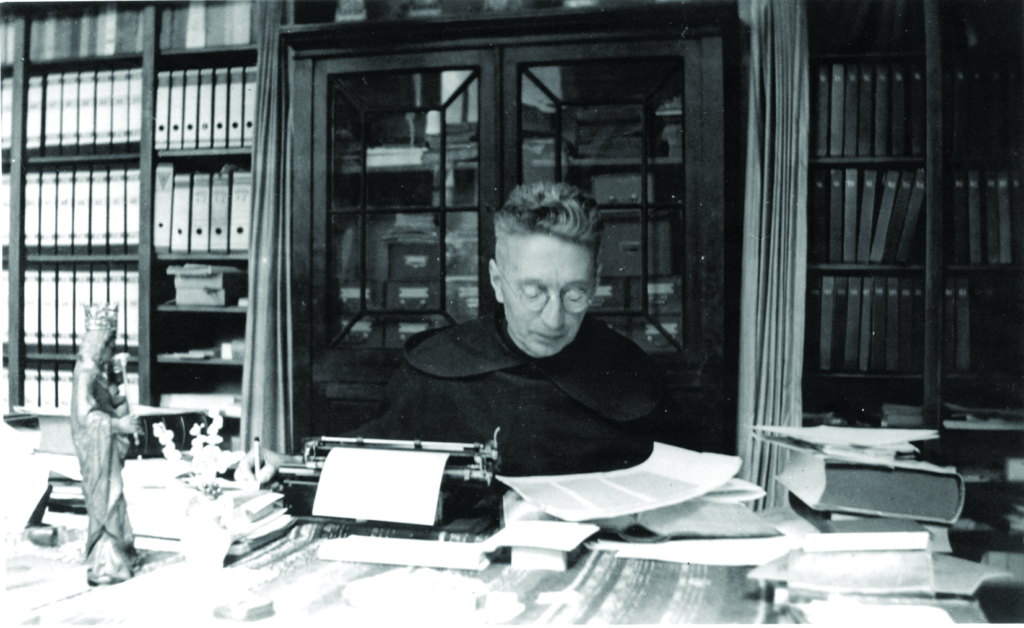

Brandsma in the study of the Doddendaal Monastery which he founded in 1930.

Brandsma with fellows of the Catholic Journalists Association in the Netherlands.

John Paul II beatified Fr. Brandsma on November 3, 1985, after a decree of martyrdom. A miracle is not necessary in this instance. In his homily the Polish Pope (who had lived during the Nazi occupation of Europe) spoke about how the Dutch priest had never lost a sense of hope. He said, “It accompanied him even in the hell of the Nazi camp. Until the end, he remained a source of support and hope for the other prisoners: he had a smile for everyone, a word of understanding, a gesture of kindness.”

The canonization miracle was approved for Fr. Michael Driscoll O.Carm., of St. Jude Parish in Boca Raton, Florida, who was diagnosed with advanced melanoma in 2004.

He underwent major surgery, with doctors removing 84 lymph nodes and a salivary gland. He then went through 35 days of radiation treatment. Doctors said that his subsequent recovery from Stage 4 cancer was scientifically inexplicable.

Fr. Driscoll recalled that his doctor told him: “No need to come back, don’t waste your money on airfare in coming back here. You’re cured. I don’t find any more cancer in you.”

According to Michael O’Neill, the “Miracle Hunter,” this is one of approximately 30 miracles that have been approved by the Holy See in the causes of saints, that have happened in the United States. Two of the doctors involved in the case that have testified to his cure being miraculous are Dr. Anthony Dardano, Sr. (associate dean of Florida Atlantic University’s medical school and a parishioner of St. Jude’s), and his son Dr. Anthony Dardano, Jr., a plastic surgeon, who treated Fr. Driscoll for a skin graft.

St. Titus Brandsma now joins St. Maximilian Kolbe, OFM Conv., and St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, OCD, (St. Edith Stein), as the canonized saints martyred during the Nazi Holocaust. According to Peadar Laighleis of the Irish publication The Brandsma Review (named after our saint), this is in addition to 147 Blesseds who perished during the Nazi persecution, and several hundred causes of saints being investigated in those years.

May their powerful witness never be forgotten, as John Paul II said in Fatima in 2000, when he said the Church should “rewrite the martyrologies.” St. Titus Brandsma’s feast day is now on July 27.

Facebook Comments