By Lucy Gordan

Tempesta’s Capture of Jerusalem in “Painting with Stone/Landscape and Architecture” (photo credit: Galleria Borghese)

May 6, 1527 was a tragic day in the history of Rome. Angry at not having been paid, some 34,000 mercenaries of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, many of whom were German followers of Luther known as Landknechts, mutinied. They forced their commander, Charles III, Duke of Bourbon, who was killed in the assault that followed, to descend on a nearly defenseless Rome. Although a small militia and some 200 Swiss Guards of Pope Clement VII’s (reigned 1523-34) attempted a desperate defense, they were hopelessly outnumbered and 147 Guards were massacred. The 42 who survived whisked the Pope along the secret passageway, known as il passetto, from the Vatican to the nearby fortress of Castel Sant’ Angelo, where he took refuge. Elsewhere, throughout the city with no one in command, total chaos broke out, resulting in ruthless mass murders and widespread pillaging. Churches and monasteries as well as the palaces of prelates and cardinals were looted of their artworks and other valuables and many destroyed, their owners held at ransom. So was the Pope, who after a month, agreed to cede the cities and surrounding territories of Parma, Piacenza, Civitavecchia and Modena to the Holy Roman Empire and pay 400,000 ducati in exchange for his life. He escaped disguised as a peddler and took shelter first in Orvieto and then in Viterbo. When he returned in October 1528, Rome was a changed place: its population had dropped from 55,000 before the Sack to 10,000. An estimated 10,000 of these had been murdered; the others, including Imperial soldiers, had died in the aftermath either from starvation or diseases caused by the huge piles of unburied corpses in the streets.

Needless to say, the catastrophic Sack of Rome brought an end to the High Renaissance epoch in Rome, scattering afar Raphael’s followers and emerging Roman Mannerists, not to mention the once wealthy patrons, now without financial means. Nonetheless, the Venetian painter Sebastiano Luciani (1485-1547) escaped to Castel Sant’Angelo with the Pope and remained with him throughout his exile and his return to Rome. (He became known as Sebastiano del Piombo after Clement VII gave him the lucrative court position of piombatore, the official who sealed important documents with lead stamps, in 1531.)

Devastated by the destruction of the all the frescoes and works of art painted on canvas, Sebastiano revived an ancient practice mentioned by Pliny: the technique of oil painting on stone: slate, marble, agate, alabaster, lapis lazuli, touchstone, and limestone. He, Pope Clement VII, and several contemporary artists firmly believed that stone, as opposed to fragile canvases and wood panels, would confer immortality to painting. The “stone” supports also had symbolic values: St. Peter, the solidity of the Catholic Church, eternal life and resurrection. The numerous portraits on display emphasize the moral solidity of the sitter while the works on black touchstone, used to reveal the authenticity of gold, reveal value and truth as well as the artistic talent of the work’s creator. Thus, on at the Villa Borghese until January 23, 2023, is Timeless Wonder. Painting on Stone in Rome in the Cinquecento and Seicento (Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries).

On display are 60 works from Italian and international museums: the Villa Borghese itself because its founder Cardinal Scipione Borghese collected many “stone” paintings, the Uffizi, Palazzo Farnese, Naples’ Capodimonte, Villa Farnesina, Turin’s Galleria Sabauda, London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, the Getty Museum, and Ottawa’s National Gallery of Canada, for examples. The exhibition, explains the press release, “recounts not only the ambition for eternity of works of art, but also the critical debate of an era sensitive to the competition between painting and sculpture, as well as primordial materials extracted from mines, their adventurous journey to the artists’ workshops, and their place in collections, which became new venues for these debates, in palaces and villas increasingly rich in furnishings, magnets for the production of luxury goods.”

Below, Johannes Lingelbach’s painting of the Sack of Rome in 1527

The exhibition’s itinerary is divided into eight sections. “The Collection and Colored Stones” contains many extraordinary objects such as altars, cabinets and clocks shaped like buildings in miniature and embellished by small sculptures, bas-reliefs, and pictures. The most beguiling is a tabletop of inlaid marbles and semiprecious stones, its oval center instead painted.

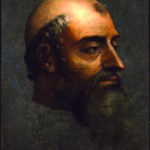

Pope Clement VII, before the Sack of Rome without a beard (1526)

“Painting on Stone and Its Creator” demonstrates how the use of metals and marbles as a support for portraits made the work not only capable of conquering time like sculpture, but also made the memory of the person portrayed long-lasting. Of particular note here are Francesco Saviati’s Portrait of Filippo Strozzi (c.1550) on African marble, the portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici (c.1560) attributed to Bronzino on red porphyry, and Sebastiano del Piombo’s unfinished Portrait of Pope Clement VII with a Beard (c.1531) on slate from Naples’ Capodimonte Museum.

Pope Clement VII with beard afterward (1531)

As Pope Clement VII’s favorite painter, Sebastiano (1485-1547) painted many portraits of this pope. Before the Sack of Rome, they were beardless. During his imprisonment Clement grew a full beard as a sign of mourning. This was a contradiction to Catholic canon law, which required priests to be clean-shaven, but it had as a precedent the beard Pope Julius II wore for nine months in 1511-12 as a sign of mourning for his loss of the papal city of Bologna to the Holy Roman Empire.

Unlike Julius II, however, Clement kept his beard until his death in 1534. His example of wearing a beard was copied by his successor Paul III and by the 24 subsequent popes down to Innocent XII, who died in 1700.

The works in “Devotion as Eternal as Marble” have occasionally been attributed to having a magical power of protection against physical and spiritual evils. Dedicated to incorruptible images of devotion, they are often small and part of the furnishings of a cardinal’s bedroom. Alessandro Turchi’s Dead Christ with Magdalen and Angels, painted on polished slate and commissioned by Scipione Borghese in 1650, was displayed in the Room of Sleep in his Villa, together with Alessandro Algardi’s Allegory of Sleep on black marble. Their dark backgrounds were considered particularly appropriate for devotional use during evening prayer.

During the 16th century iconic religious images and portraits were the most common subjects of “stone” paintings. Instead, Leonardo Grazia da Pistoia used stone to portray seductive female figures from mythology and Roman history. On display in “Immortalizing Beauty” are three of his paintings, Hebe and Lucrezia, on slate, and Cleopatra, oil on a wooden panel. Also on display is Jacques Stella’s small pendant, a copy of Guido Reni’s Martyrdom of St. Catherine of Alexandria, painted with oil on lapis lazuli, with touches of gold and enamel in a rock crystal frame.

Instead, the several works in “Allegory and Antiquity” on slate, marble and touchstone, are all dedicated to themes of ancient poetry such as Cavalier d’Arpino’s tiny Andromeda, Pasquale Ottino’s gory Medea Restores Aeson’s Youth, and Vincenzo Mannozzi’s Hell with Mythological Episodes. The backgrounds of these paintings are shiny and gleam like mirrors, thus reflecting the image of the viewer, who, while observing, becomes part of the painting.

The spooky works in “A Night as Dark as Stone,” painted on dark stones (touchstone, slate or Belgian marble) utilize the blackness of these supports for nighttime settings. They dramatize their dark scenes with the light of “fires” thanks to their golden finishes, as in Stefano della Bella’s Burning of Troy.

Eeriest of all is Jacques Stella’s Judith in Prayer shortly before she slays Holofernes, in the darkness of his tent where he is portrayed sound asleep. Instead, a saint-like Judith, although about to commit murder, is lit uncannily by the glow of a candle.

Jacques Stella’s Judith in Prayer in “Night as Dark as Stone” (photo credit: Galleria Borghese)

Pietra paesina is not a household word. It refers to the large limestone pebbles from the Arno Valley. When cut by an expert, their uneven surfaces and earthy colors, the result of centuries of mineralized infiltration in hydroxides of iron and manganese, produce a natural landscape without the intervention of a human artist. Thus, in “Painting With Stone/Landscape and Architecture,” the painters adapted their compositions, often landscapes, to the veins in this local limestone. For example, in Tempesta’s Capture of Jerusalem, the tiniest brushstrokes transform the stone patterns into the image of the city.

If other stone support was generally inexpensive, lapis lazuli, imported from Afghanistan, was precious. In “Precious and Colored Stones,” the artists used only small slivers, often carefully joined together in workshops that dealt with hardstones. This collaboration is evident in Johann König’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt. Here a sliver of lapis lazuli, representing the sky, is inlaid in pietra paesina to emphasize the miraculous spring of water that appeared to Mary and Joseph in the desert.

Johann König’s Rest on the Flight to Egypt in “Precious and Colored Stones” (photo credit: Galleria Borghese)

The passion for painting on stone lasted about a century because, when plague broke out in Rome in 1630, pieces of slate and lapis lazuli were impossible to procure. Believed to have medicinal qualities, they were ground into small pieces or powder and placed on the sufferer’s heart as a cure.

Facebook Comments