Gerhard Ludwig Müller. Archbishop-Bishop Emeritus of Regensburg, Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith.

Gerhard Müller, 66, the third name on the list, was another “necessary” choice. One of the last decisions of Pope Benedict before he resigned was to name (in July 2012) Archbishop Müller head of the Vatican’s chief doctrinal office, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith — a position that normally must be held by a cardinal.

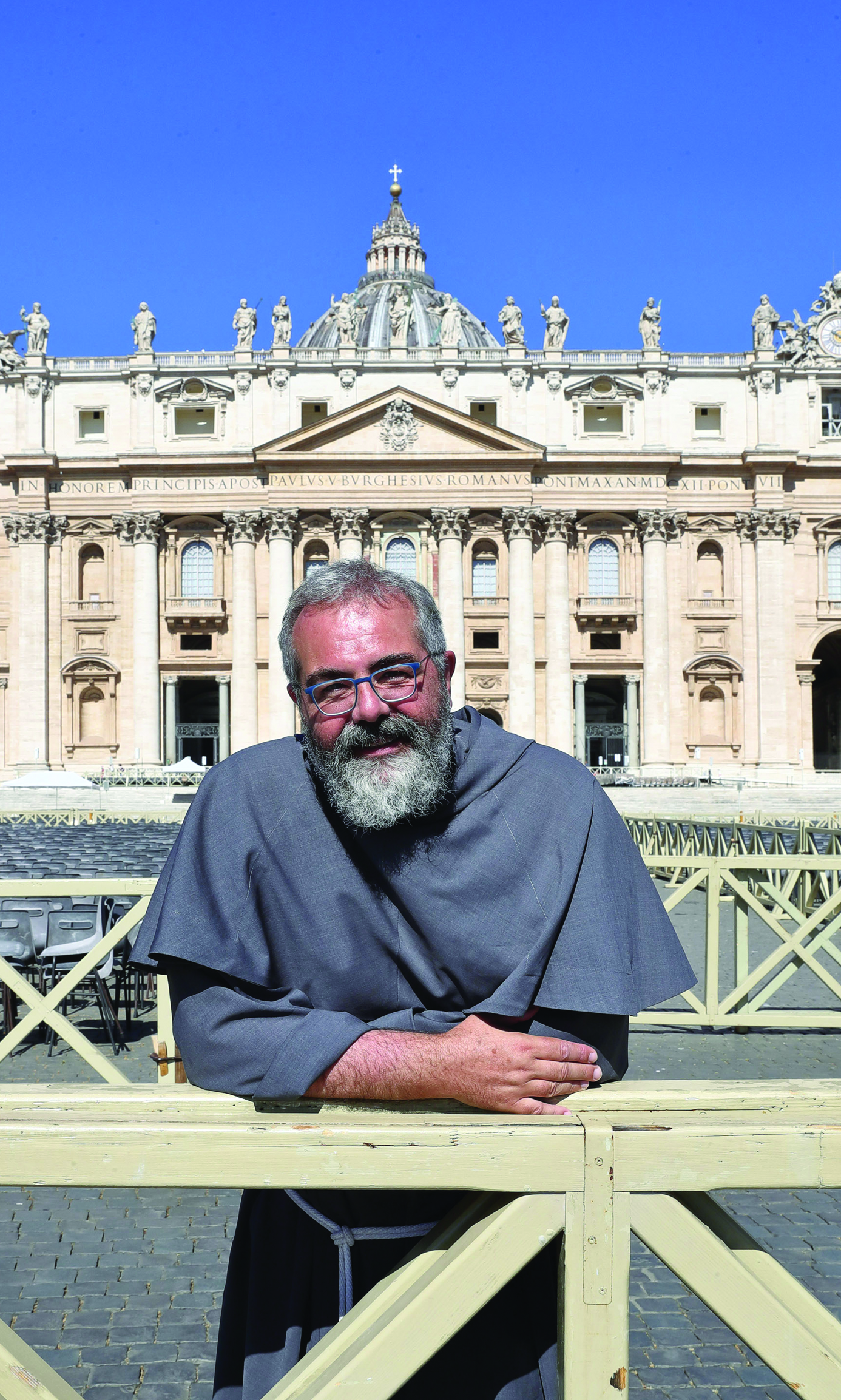

Müller, a very tall, powerfully-built man, was trusted by Benedict in part because he has been handling the editing of Benedict’s collected works (Opera Omnia). Now Pope Francis is confirming that trust.

Müller has been a close personal friend of Father Gustavo Gutierrez of Lima, Peru, considered to be the “father” of Liberation Theology. Müller met Guttierrez in 1988 and has often visited him, spending weeks in Lima in study programs. “The Latin American ecclesial and theological movement known as ‘Liberation Theology,’ which spread to other parts of the world after the Second Vatican Council, should in my opinion be included among the most important currents in 20th century Catholic theology,” Müller has said.

Müller is also known for having said that the Church’s position on admitting divorced and remarried Catholics to the sacrament of Communion is not something that can or will be changed. But other German Church leaders, including Cardinal Walter Kasper, have recently gone on record saying the teaching may and will be changed. So this is one important area of discussion and potential tension in coming months, leading up to the Synod on the Family in October.

More than a year ago, the archbishop sat down at some length with British journalist Mary O’Regan. She described being ushered into his presence: “A door opened and in strode the tall figure of Archbishop Müller. He had a poker-straight posture, a shock of white hair, lively brown eyes and a warm smile. His handshake was firm, gentle and not at all harsh. Most disarmingly, he was evidently keen to do an interview with a journalist who had just flown in from London. His openness was so refreshing that my nervousness disappeared.” So here we have a man who makes his interlocutors feel at ease — a far cry from a “Grand Inquisitor.”

“When I was four, the bishop of Mainz came to our local village of Finthen to administer the sacrament of Confirmation,” Müller told O’Regan. “When I saw the bishop with his staff and miter, apparently I said to my mother: ‘That’s what I’d like to be! A bishop!’”

Müller said his parents were “very surprised” to learn that he had a vocation, because “they were humble people and couldn’t imagine that their son would become a priest.” His father was “a simple worker” at the German car manufacturer Opel. The youngest of four children, he grew up in a close-knit, working-class family in a village that had been a Roman settlement. He emphasized that his parents were very diligent in their practice of faith and “always, always practiced every detail of the faith, not leaving anything out.”

Initially, his mother was the biggest influence on his faith, and as a family they recited the rosary every day. With a tinge of sorrow in his voice, he said that his parents did not live to see him consecrated bishop of Regensburg in 2002.

Müller entered into a deeper discussion with O’Regan about his priestly vocation.

“Growing up, I had been an altar server and always involved in Catholic youth groups,” he said. “Before seminary I was taught by priests in secondary school, and so going to live with them in the seminary in order to train as a priest was not so different. Of course you must ask yourself if you can live without wife and family. You must find out if you are willing to sacrifice your life, in the Christological sense of sacrifice. Every mother or father gives their life for their children and their family. The priest, as father of the family of God, has to give his life and must not remain self-centered or egoistic. We must live as Jesus did, to give our life for the other.”

Ordained in 1978, Fr. Müller was an assistant priest in three parishes and taught catechism in surrounding secondary schools. In 1977, he submitted a dissertation on the Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s sacramental theology. In 1985, so that he would be eligible to be a professor of theology, he wrote a second doctoral thesis on Catholic devotion to the saints. The “Karl Rahner connection” is that Archbishop Müller’s doctoral supervisor for both his theses was Professor Karl Lehmann, who received his doctorate under Karl Rahner. In 1986, Fr. Müller was made professor of Catholic dogmatic theology in Munich, a position he held until John Paul II appointed him bishop of Regensburg.

He said with deep seriousness that what he enjoys most about his post is “being in the service of the Holy Father — and trying to make unity possible for all believers.”

One of Müller’s tasks is to oversee the reconciliation process with the Society of St. Pius X. “There remain misunderstandings about Vatican II, and these must be agreed upon. The SSPX must accept the fullness of the Catholic faith and its practice. Disunity always damages the proclamation of the Gospel. The SSPX need to distinguish between the true teaching of the Second Vatican Council and specific abuses that occurred after the Council, but which are not founded in the Council’s documents.”

He said that he is in no way “against” traditionalist Catholics and does not have a personal dislike of the SSPX. “But we need to address the practical issues that cannot be ignored. Many in the SSPX have learned theological errors, and they must learn the true sense of the tradition of the Catholic Church. It’s not about conserving a certain time stage in history, it’s a living tradition.”

—Based on an article by journalist Mary O’Regan in the Catholic Herald, December 19, 2012

Facebook Comments