Pope Francis greets Vatican journalist Andrea Tornielli aboard on the Papal Flight to Brazil on July 22, 2013.

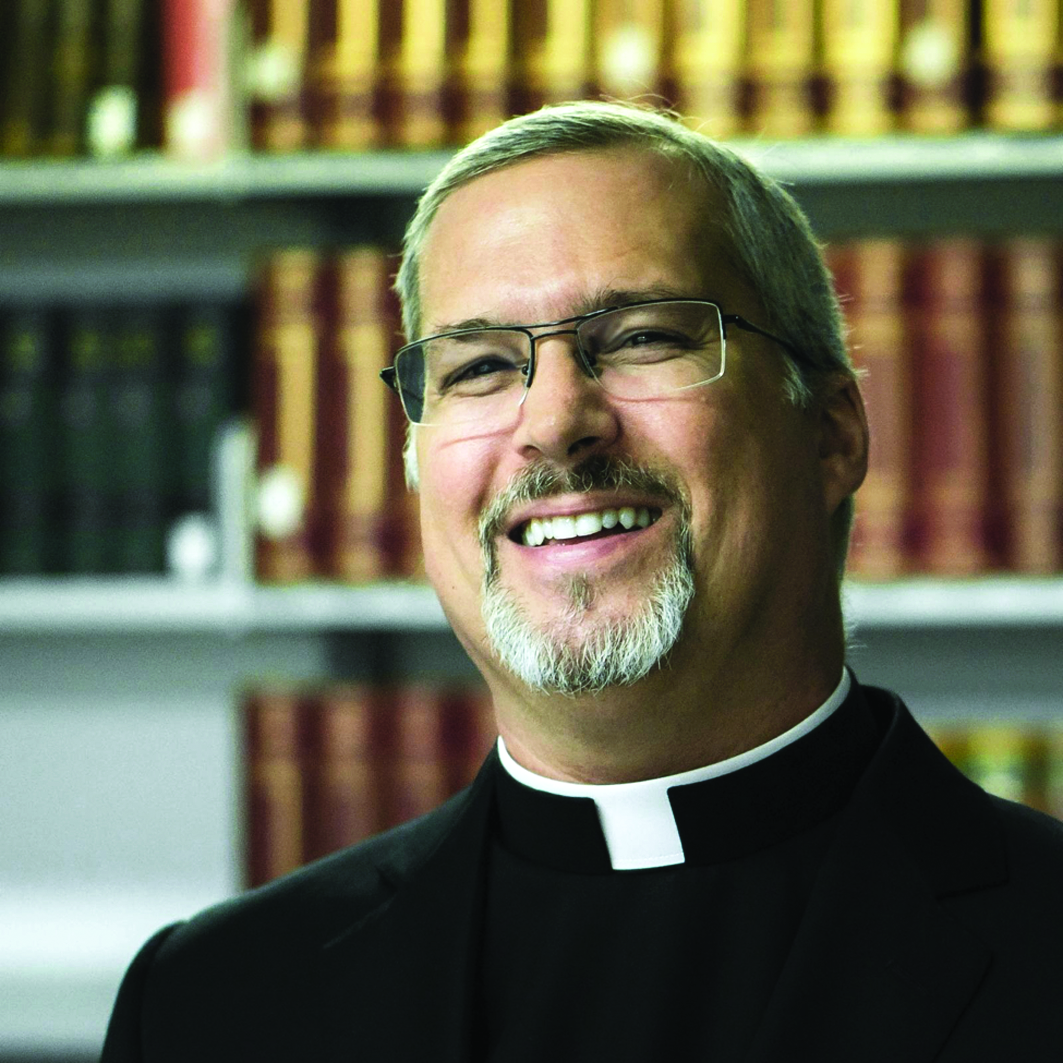

Vatican correspondent Andrea Tornielli talks about his new book on Pope Francis and world economics.

Andrea Tornielli is one of the world’s most prominent Vatican correspondents and author of more than 50 books. Born in Chioggia, Italy, near Venice, in 1964, he first worked for Communion and Liberation’s magazine Il Sabato, then for 30 Giorni (1992-96) and the center-right daily Il Giornale (1996-2011). The former director of the Catholic online journal La Bussola Quotidiana, he is currently the coordinator of Vatican Insider, the religious information site of the center-left, Turin-based daily La Stampa, and a regular contributor to the monthly apologetics magazine Il Timone.

He first met the future Pope Francis in the early 2000s, through mutual friends from 30 Giorni. His friendship with Jorge Mario Bergoglio has continued past the papal election of March 13, 2013. Tornielli interviewed the Argentine pontiff in December 2013, and again for his new book, Papa Francesco: Questa Economia Uccide (Pope Francis: This Economy Kills) (Piemme Publishing), which he wrote with Giacomo Galeazzi, his colleague at La Stampa. My interview with Tornielli is mainly about the contents of that book.

Andrea, in Pope Francis: This Economy Kills — a book that features an interview with Pope Francis himself — what pontifical documents did you and co-writer Giacomo Galeazzi use as a basis for your reflections? As you know well, there is undoubtedly a great difference in teaching authority between an apostolic exhortation and the replies given during an interview, sometimes given at an altitude of 30,000 feet and with “risk of accidents”…

Andrea Tornielli: Most of the teaching referred to in the book is based on talks that were written down, although there are some exceptions, such as some off-the-cuff comments he made during a meeting with workers in Cagliari, Sardinia. To be sure, the basis of our work was the exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, which can clearly be seen as the document that sets the tone of his pontificate. We wanted to show how this Pope, through his many discourses, intends to revisit the entire social doctrine of the Church. The stances he takes in them fit into a precise pathway, and among them are passages that we don’t hesitate to define as explosive, even if many have been forgotten.

Why do you mention revisiting the “entire” social doctrine of the Church? Wasn’t it enough to say “the Church’s social doctrine?” It seems to me that you didn’t add “entire” simply by accident…

Tornielli: In fact, it was no accident. Up until 1989 we had been living in a world divided into two blocs, and characterized, in the West, by the fight against communism. In the official stances of various Popes, care was taken, naturally, not to use ambiguous expressions that might risk giving rise to the accusation of furthering the communist cause. Besides this, we should not forget that, in the 1970s and 1980s, part of the Catholic world was trying to adjust the aim of the Church’s social doctrine.

“Adjust the aim”… can you explain what that meant, in the context of that era?

Tornielli: Let me give you an illuminating example: Michael Novak, the American scholar, stated openly that, since John Paul II came from Poland, they had had to teach him a bit of economics for him to be able to write his 1991 encyclical, Centesimus Annus, which adjusted the aim of the preceding Solicitudis Rei Socialis and Laborem Exercens.

Each of your book’s chapters begins with a quote from the Church’s social doctrine, mainly from Popes. There are several passages from the encyclical Quadragesimo Anno (1931) written by Pius XI 40 years after Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum (1891). Here is an excerpt that still rings true today: “In the first place, it is obvious that not only is wealth concentrated in our times, but an immense power and despotic economic dictatorship is consolidated in the hands of a few, who often are not owners but only the trustees and managing directors of invested funds which they administer according to their own arbitrary will and pleasure…”

Tornielli: There are pages of the Church’s social doctrine that have been almost completely forgotten. The encyclical Quadragesimo Anno is a perfect example of this: it was written in 1931, a short time after the stock market crash, and in it Pius XI assumes very forceful positions. Being that we are in an economic-financial crisis period which, given its ramifications, is very similar to the crisis of 1929, it surprises me that these prophetic pages haven’t been rediscovered and appraised. Not only that: I am even more surprised that there aren’t any Catholics working to make these pages part of social and political programs. In fact, there are some passages from Pius XI – and I refer here to the current situation in Italy — which today are more “leftist” than what even the Italian political Left proposes. Look, for example, at the passages that refer to the excessive power of the markets. In his talks, Pope Francis helps shed light on sections of social doctrine that have been obscured…

According to some Catholics, he sheds too much light on them, to the detriment of other aspects of social doctrine, such as the so-called “non-negotiable principles…”

Tornielli: I don’t think we can honestly say this. It is true that Pope Francis places emphasis on different aspects of it, but it must also be recognized that these had been neglected…

There are those who hold that, when speaking publicly on the “non-negotiable principles,” Pope Francis is a bit fickle, swinging back and forth, as has emerged in several in-flight press conferences, giving the impression that they are no longer as important as they were in the recent past…

Tornielli: Beyond the quips made during press conferences — which may show good or not-so-good timing — I believe that anyone who has the intellectual honesty to read completely through his answers to journalists understands the Pope’s real meaning on this subject…

Let’s not delve deeper into this subject, and let’s turn instead to the main theme of this interview. Of the many observations and complaints, especially from the Americas, over what Pope Francis has to say about the economy, the most drastic has been, “We have a Marxist Pope” or, in an even more negative variation, “We have a communist Pope”…

Tornielli: In a way, this is the least harmful complaint, because it is objectively coarse and crude. And this type of comment has been made by people who are not at all familiar with the Church’s social doctrine, such as Rush Limbaugh. The Pope has replied to such comments — also in the interview at the back of our book — stating that he does not feel offended by them: in every case, Marxist ideology remains unacceptable…

Let’s move to the complaints about what has been defined as the Pope’s harsh criticism of capitalism…

Tornielli: The Pope’s criticism of capitalism is not a blunt, generalized one: rather, it is a criticism of a certain kind of capitalism that has produced the economic system we live in today. It is a system that perhaps has nothing at all to do with capitalism, dominated as it is by all-powerful markets, founded by people who bet on how much they will be able to earn in a matter of seconds, completely detached from the real economy. A few fluctuations of the stock market can drive up prices of basic necessities and plunge entire segments of the population into poverty: these are phenomena that cry out for God’s justice, and Christians should question whether the current system needs to be radically reformed.

Another criticism against Pope Francis, launched usually from the United States, is that, since he is only familiar with the Argentine economy, or at most the Latin American one, he isn’t knowledgeable enough about the global economy to be in a position to criticize it. The already-cited Michael Novak is one of these critics: he affirms, among other things, that Argentina has never experienced real capitalism, and therefore, whatever Pope Francis says might be fitting for Argentina, or even the whole of Latin America, but certainly not for the whole world… Kishore Jayabalan, the director of the Acton Institute’s Rome office, states that “Francis’ experience in Argentina, and the kind of economic mismanagement he observed in that country, is light years away from what supporters of the free market would like to see happening”…

Tornielli: I think that this is the most destructive and haughty criticism that can be launched at the Pope: “Since he comes from the Third World, he shouldn’t presume to pronounce on subjects he knows nothing about. But if he really insists on it, he’d better let us guide him through it: we’ll teach him all about economics, so that he can go and write lovely encyclicals that laud the Church’s commitment to the poor, but avoid judging the system.” I wonder, do these people know that there exist economic structures of sin? John Paul II said it, not Ernesto Che Guevara.

Surely these are major friction points throughout the Catholic universe, not just in the US?

Tornielli: It is true that this Pope comes from “the ends of the earth.” But still, he is not from outside the earth itself. Argentina started going through a serious economic crisis a decade before we did, and has known rampant secularism, the challenge of a strong evangelical movement, “gay marriage”… So while it is true that this Pope comes from the “ends of the earth,” he knows the world very well.

There are some who underline what has been seen as a “Peronist” line on Pope Francis’ part, a Pope who is a bit of a descamisado [“shirtless,” a nickname for followers of Juan and Eva Peron]…

Tornielli: I must disagree on this, too…

But it is also true that he breathed at least a little “Peronist air,” in his youth…

Tornielli: That would be the equivalent of saying that John Paul II was a bit of a Marxist, since he lived in Poland…

But Poland remained Catholic; it resisted and refused that Marxist air. It was different in Argentina, where the majority were Peronist… and the entire nation exalted Evita Peron…

Tornielli: We all know that Jorge Mario Bergoglio served for 20 years (as auxiliary bishop, coadjutor, and archbishop from 1998 on) in Buenos Aires, and that is a metropolis where you can find slums right next to high-class neighborhoods. When he speaks of the poor, he does so from extensive personal experience. I don’t understand why there are those who call him descamisado… maybe because he welcomes into the Vatican types of people who had never been welcomed there before, or maybe because he invited some cartoneros (trash pickers) to be in the first row at his installation Mass. But really, it is in the fullness of Church tradition to show great attention to the poor. I don’t understand certain reactions, like the people who make such a fuss over three new showers and a barber shop for the homeless within the colonnade of St. Peter’s. Do they have any idea what Rome has always been like, through these past two thousand years? It was normal to find the poor sleeping in the atria of Rome’s basilicas. So these new showers are not going against tradition: they are a reflection of the truest tradition of the Church of Rome!

Let’s go back to the situation of Argentina’s poor. Michael Novak highlighted that, in Argentina, the poor live in a situation that is “immobile, or static,” while in other countries — such as the United States and, generally, other Western countries, but not only — the poor are beneficiaries of upward social mobility. The Pope, however, criticizes the “trickle down” theory of the current economic system…

Tornielli: He criticizes it, revealing that reality is not as rosy as certain American circles paint it to be. There are positive points, but also very negative ones. In a dramatic way, it can be seen in daily life, even in certain Western countries today. The Pope gives us all a picture of reality: he wants to spur Catholics to return to being leaders in social life, as they so admirably did in past eras, strong in the treasure that is the social doctrine…

Many insist, though, that globalization was supposed to bring about better living conditions for large swaths of the population, across the world…

Tornielli: The Pope has said clearly, many times, that globalization has its positive points: it has allowed many people to rise out of poverty. But many more people have fallen into poverty: this is a fact, not a figment of his imagination. There are also Catholics who maintain that economic instruments are neutral in and of themselves, that their worth lies in the use that we make of them. But this judgment doesn’t take into account that there are structures, basic supporting structures of this system, that are sinful in and of themselves. The fact that in our nations the index that measures wealth is the market spread, and not the real conditions people live in, indicates that there is nothing left of what is truly capitalistic, since capitalism is tied to the real economy.

We are living in a time in which the political sphere has bound itself hand and foot to an economic-financial system based on the speculative bubble, for which a few gamblers decide the destinies of us all. The only urgent matter is that the market spread be sustainable. If there are people (such as in Italy’s case) who have fallen from middle class to poverty, that is considered merely collateral damage.

What is reigning now, as Pope Francis continuously states, is a culture of waste. Thus, calling the system into question, reflecting on why this is happening, and trying to translate the Church’s social doctrine into social and political programs become an imperative for every Christian who aims to live as such…

Even what the Pope has had to say concerning the weapons trade and his feelings toward war have been compared by some to Lenin’s words on the links between capitalism and imperialism: the Economist wrote about it…

Tornielli: Benedict XVI wrote pages of commentary against the weapons trade: does this make him a Leninist? “Marxist” and “Leninist” aren’t bad words in and of themselves: Marx may have written something right, and even Lenin may have, too. I wouldn’t want to be called a Leninist for this, because I certainly am not one. But no one in their right mind, no one who hasn’t absorbed all sorts of media propaganda, believes that wars are carried out solely for religious reasons, or for freedom and democracy. It is common knowledge that wars are also fought to bolster the arms trade…

It is enough to read about the repugnant weapons trade tied to the situation in the Middle East, bolstered decisively by the invasion of Iraq, and followed by the revolt in Syria; what joy this all gave to arms merchants, who prosper even in consolidated Western democracies…

Tornielli: Where do the state-of-the-art weapons being used by the Islamic State come from?

The Pope often states that our current economic system has serious, negative consequences, also in the field of anthropology…

Tornielli: An example is the imposition of models that damage the identity of entire populations, which are often threatened with economic blackmail: “I’ll lend you money, if you practice a certain brand of politics.”

This is a real ideological colonization, which the Pope denounced during his latest apostolic mission to Sri Lanka and the Philippines. These kinds of impositions serve to “cement over” every kind of diversity, cultural wealth, and religious traditions, making them conform to the world level.

This is a new form of colonialism, not by any means less grave than the historical, political kind: the new passwords are declining birth rate, de-structuring of the family, gender ideology, schools that educate children to be politically correct…

In conclusion: what spurred you and Giacomo Galeazzi to write this book?

Tornielli: Our aspiration was to stir up the waters, to encourage the Catholic world to open up more to discussions about a subject as vital as the Church’s social doctrine, in its entirety, in the hope that someone might manage to translate it into a concrete program.

Facebook Comments