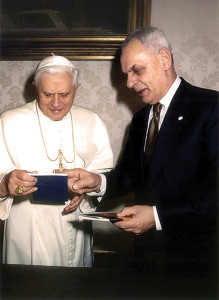

Italian Senator Marcello Pera with then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. Though not a Christian believer, Pera agreed with Ratzinger that Europe needs to rediscover its Christian soul or risk losing all.

Who is Marcello Pera? A seventy-one-year-old Italian philosopher and politician, known for his friendship with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, which began during Pera’s years as president of the Italian Senate (2001-2006). They continue to be good friends, and will in fact be meeting this month at the Mater Ecclesiae Monastery within the Vatican walls: theirs is a friendship between a non-believer and a believer, both worried about a Europe that misunderstands its Christian “soul,” finding itself adrift in the great sea of relativism. Their mutual cooperation has found expression in three collections of essays: Without Roots (Senza radici, Mondadori, 2004, written alternately by the two on subjects such as Europe, relativism, Christianity and Islam), The Europe of Benedict (L’Europa di Benedetto, Ratzinger, Cantagalli, 2005, with an introduction by Marcello Pera, later published as “Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures”), Why We Must Call Ourselves Christians (Perchè dobbiamo dirci cristiani, Marcello Pera, Mondadori, 2008, with a letter of introduction by Benedict XVI).

We met with Pera in Rome, on the second floor of the Palazzo Giustiniani in the city center, in the spacious study provided to him as Senate President Emeritus. We spoke with him about the beginning and development of his friendship with Pope Benedict, its basis, Benedict’s renouncement of the papacy, and today’s Europe and its troubling political and cultural condition.

Senator, how did you first meet Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger?

Marcello Pera: I went to see him at his office at the Prefecture of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, since I had been impressed by his many writings. I had been most struck by his book, Truth and Tolerance. I hadn’t thought that relativism had managed to penetrate certain Christian theological circles; he illuminated me on the subject, and started me worrying. If even Christians renounce the idea of truth, what is our religion going to be reduced to? Moreover, what consequences does a Christianity confined to a mere “narrative,” as they say nowadays — something good, but reduced to one good thing among many —have for our identity?

What struck you at first about the cardinal?

Pera: His character and his intellectual side. I felt right away that his personality was one of greatness. Lucid, clear, direct, with methodical and very articulated thoughts. He considers things with attention and respect for the other, and he doesn’t hide any problems. He speaks in a secular way, the same as how he writes, not for a homily or catechesis, but with rigorous concepts and reasoning. He listens to your questions and he doesn’t shy away from difficulties. I felt completely at my ease the entire time, as one does in the presence of a good teacher. In my life, I have met a few truly great people, among them Karl Popper, and Joseph Ratzinger is one of them. He is not only a theologian, but a great philosopher as well: open, critical, profound, and with vast cultural knowledge in many areas. And he has a quality that only the truly great possess: intellectual modesty, which allows him to bring together a critical, even self-critical, spirit, with the truth in which he believes. Besides all this, there is the individual aspect: he is courteous, helpful, attentive, scrupulous. And above all, frank. I can say that, as soon as we began speaking about relativism, which was the subject that had first drawn me to him, I observed with caution that it seemed to me that there was a need, on the Church’s part, for more force of reaction. He surprised me because he said, “Many of our bishops lack the courage.” I thought it, but he said it.

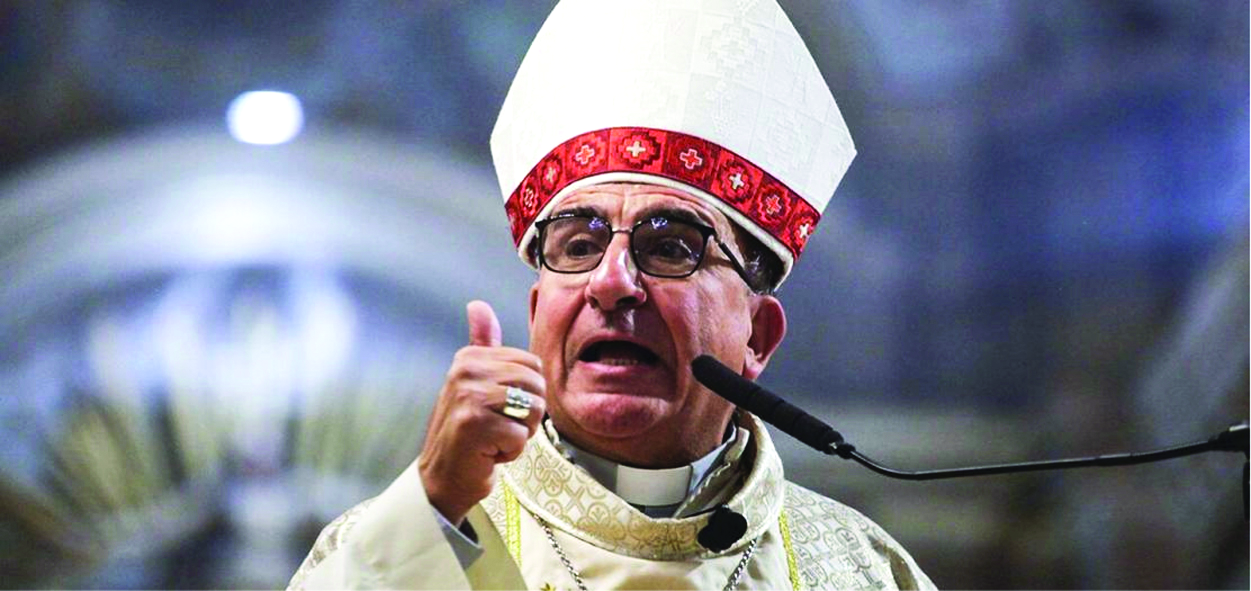

Marcello Pera greets St. John Paul II during his visit to the Italian Parliament in 2002.

How did your relationship develop?

Pera: We saw each other several more times, never discussing political matters in the strict sense. One item on the daily agenda, even in Parliament, was Europe. And one day, I asked him to hold a conference in the Senate library, on the cultural and spiritual situation in Europe. That was how Without Roots was born; it was no longer a private conversation, but a public and written one.

What subjects did you find yourselves agreeing on?

Pera: Besides Europe, which I also considered, and still consider, to be a spiritual wasteland, there was the relationship between secularists and believers. This is also a typical feature of Ratzinger’s work: he speaks with the secular-minded and challenges them. His question to the secularists is always the same: on what do you base the values you hold so dear? How do you argue for them and defend them, today especially when they are attacked from within and without? We know the answer, the same as it has been from the Enlightenment to now: reason.

All right, but what does reason offer when the discussion is about reason itself? If a given group of people comes to the conclusion that it is “rational” to allow, let’s say, abortion, and a different group negates it, whose reasoning is right? And when European reason finds itself challenged and attacked, let’s say, by Islamic reason, whom can we turn to, and who can solve the dispute? Proposing “dialogue,” as not only secularists but also large sectors of the Church tend to do today, is not enough: dialogue isn’t dialogue if the criteria for dialogue aren’t present. Does reason create these criteria, or is it reason itself that uncovers them? And if reason uncovers them, how exactly does it manage to do so? Through illumination? Ratzinger, who is as much a lover of reason as any of the secularists, brings the base of the discussion to earth on this point. And thus the discussion comes back to the limits of relativism. These are fascinating problems, and extremely relevant politically, even if they don’t seem so at first glance.

Did your friendship continue even after Joseph Ratzinger became Pope in 2005? In what way?

Pera: Yes, we met afterwards, too, and our friendship has continued. I still thank him, and I will always be in his debt, for the occasions for private meetings that he set aside for me. It wasn’t easy for him, but he has always been a generous person. I will never forget him. Nor will I ever forget the preface that he insisted on writing for my book, Why We Must Call Ourselves Christians. It is only a couple of pages long, which doesn’t seem like much, but reading it carefully you can find a real treasure.

Did Pope Ratzinger’s renunciation surprise you, or strike you? Do you feel it was a rational act? In your opinion, what will the main consequences of that act be?

Pera with Pope Benedict XVI.

Pera: It saddened me, but it didn’t surprise me. It isn’t surprising when someone starts getting old or losing his strength; at most, one feels sorry over it. But I understood his gesture, and I maintain that I understood it. It is as if he knelt in front of the Lord and said, “Lord, what do You desire of me? How can I serve You, now that my strength is receding? In what way can I bear Your Cross and satisfy the needs You placed on my shoulders? How can I serve Your Church, in what is such a difficult moment for Her, if I don’t have enough energy to correct Her?”

There are many, also inside the Church, who have had a hard time comprehending his renunciation, and I understand them, too. At the same time, I see this as intellectual laziness, an attitude of “since it has never been done, he can’t do it, either.” This laziness can become arrogance. Instead, it needs to become an act of faith, as indeed it was for Benedict XVI. In terms of consequences, we can’t really talk about them, simply because the Pope’s action was a prophetic one, and prophecies can’t be measured in the short term. They are acts of God.

Are you still friends with the Pope Emeritus? In which way?

Pera: Yes, I still visit him, and it is always a great joy, a blessing. Our dialogue and our intellectual communion continue. And I am immensely glad when I go to see him in his apartment and exchange opinions with him. He has the same intellectual lucidity now that he has always had.

The friendship between you is illustrated in Without Roots, the book we just mentioned. In that collection, written 10 years ago, you both contribute essays, alternately, on Europe, relativism, Christianity and Islam. Since 2004, have there been any changes in these areas in Europe? For better? For worse?

Pera: In particular, one thing has changed: these matters —namely Islam, the relationship between cultures, European identity, the role of Christianity — are practically not discussed at all anymore, whether in political or Church spheres. Fear has gained the upper hand; there is a lack of courage. People turn their heads and get on with their lives, as if hiding these problems helps solve them. And this has been happening even though those same European heads of state had started to be open to discussing these issues, and mainly through Benedict XVI’s merit. Do you remember when the secularist [French President Nicolas] Sarkozy came to Rome and stated that France was a Christian nation, and that secularism wasn’t anti-religious? He probably didn’t believe that sincerely, but at least he brought the matter to light. Today no one says anything like that: everyone is scared to upset the “dialogue,” which in this case means a conversation among the mute, or, more precisely, a conversation between those who have strong opinions about themselves, and proclaim it by shouting and yelling, and the West, opinion-less and not seeking to define itself, thus remaining silent. No one even gets upset over the rising martyrdom of Christians around the world.

The Chancellor of Germany since 2005, Angela Merkel, and Italy’s new Prime Minister Matteo Renzi.

How do you evaluate the results of the European election at the end of May from the point of view of anthropological problems? Can we really expect the new European Commission and its Parliament to take up life, family and educational issues, according to the prospects set out by both Joseph Ratzinger and yourself?

Pera: I truly hope that the Commission and the European Parliament won’t be discussing these issues, considering what would come out of those mouths. I can’t see anyone in Europe wanting, even minimally, to take on matters of identity and culture. No one has the courage to refer to Christian tradition. And if anyone does try, the others — meaning the so-called “respectable majority,” the dialogue-seeking accommodators — swiftly silence him by labeling him “xenophobic” or “racist.” Maybe in some cases those labels really do fit, but how can it not be understood that the very act of remaining silent where our identity is concerned, and hiding it as if it were a fault, generates precisely that kind of xenophobia? Nothing doing: today’s Europe talks about “parameters” for overcoming the economic crisis, and it doesn’t even recognize the correlation between this crisis and crises of the cultural and spiritual sort. As if a people, hundreds of millions of people, were a variable to be adjusted, or budget data to be corrected. What a disaster! And what an expanded disaster, if this new European spirit penetrates into the United States!

Are there forces — old or new — in the new European Parliament that could help awareness of this point of view to be more widely shared?

Pera: I already said it, there are many “xenophobes.” But since one does not enter into discussions with xenophobes, it comes to pass that the so-called “xenophobes” become just that, and the others, using xenophobia as an excuse, stay silent.

Today Germany is led by Mrs. Merkel, and Italy’s leader is Mr. Renzi, heads of two ample European political “families” with responsibility for governing. Have they ever learned, and, if so, do they remember, that their fathers, Adenauer and De Gasperi, spoke of a “Christian Europe”? That through that identity they saw the valid path for fighting nationalism, xenophobia, and fear? I certainly hope so.

As far as I am concerned, I am a pessimist, and very worried. An ill wind is blowing through Europe, and I remember that the First World War broke out at the heart of the Old Continent when no one wanted or expected it. And yet, when that shot was fired, we were at the height of our civilization: four years later, the world that survived the graveyard was a totally changed one.

On the last day of its mandate, the outgoing European Commission refused to allow Parliament to examine the pro-embryo petition, “One of Us” (that had collected no fewer than 1.8 million signatures, in nearly all EU countries). How do you evaluate that decision?

Pera: What can I say in response? Had a similar petition in favor of homosexual marriage or euthanasia been presented, even with few signatures, it would have passed right away. It has already happened. After all, don’t they say that it’s all about “conquering civility”?

The next day, the Italian Chamber of Deputies — led by a fervent admirer of Pope Francis — in a great rush, and shaking up the day’s official agenda, approved so-called “express divorce.” So, while at the European level and in the Italian Parliament there is an outpouring of applause for Pope Francis, when there is a vote in these “anthropological” areas, many who applaud him are quick to vote against content proposed by the Pope himself. How do you view this attitude?

Pera: I can only hope that the huge crowds that gather around the new Pope aren’t made up of the same people that approve European Parliaments when they discuss ethical matters.

Among declared Catholics, there are those who maintain that the fight in anthropological areas shouldn’t be fought in Parliament, but rather at the parish level, that it would have more effect that way. What are your thoughts?

Pera: It would indeed be more effective that way. It is a battle that has to be fought in families, schools and the local streets and squares, in parishes and from pulpits, and in all information outlets, before it ever reaches Parliaments. Because Parliaments are no longer made up of elitists who make decisions that in turn educate the masses. Instead, they are sounding boards, used for compliance with what is happening outside. They ratify; they don’t decide.

A pro-family march in France.

As we wrap up our discussion: on anthropological themes, would it still be possible for a strong alliance to emerge in our society, including both believers and non-believers, wishing to adhere to the fundamental principles of the Church’s social doctrine on life and the family? In France, for example, there has been a massive participation of mainly Catholic but also Jewish, Muslim, Protestant and agnostic citizens, at the Manif Pour Tous, though President Hollande — a real champion of democracy — chose to play down, if not ignore, this expression of popular will…

Pera: No, I don’t feel it is possible, or at best it would be highly unlikely, at least in this era. It is also true that the Church is showing herself to have problems with her own social doctrine. She is also downplaying problems. What we lack today is someone to write De civitate Dei while the Roman Empire is falling. And that was the Roman Empire, not the European Union! As you can tell, it’s best if we draw to a close now.

Facebook Comments