Interview with the Apostolic Nuncio Bernard Auza, new Permanent Observer of the Holy See to the United Nations in New York.

Born in the Philippines, in Talibon, fifty-five-year-old Archbishop Bernard Auza was sent in 1985 to Rome, where he attended the Pontifical Ecclesiastical Academy (the Vatican’s diplomatic school). He has degrees in theology and canon law. He entered the diplomatic service of the Holy See and served in Madagascar, Bulgaria and Albania before being called back to Rome in 1999, to serve in the Section for Relations with States of the Vatican Secretariat of State. From 2006 to 2009 he was posted at the Permanent Mission of the Holy See to the United Nations in New York. In July 2009, he received his episcopal consecration in St. Peter’s Basilica, and became the Apostolic Nuncio to Haiti, “where,” then-Secretary of State Cardinal Bertone said in his homily, “you will be an apostle of unity and communion, reconciliation and peace.“

As we know, things didn’t go as foreseen: on January 12, 2010, a terrible earthquake struck that Caribbean country. On July 1st, 2014, Auza was appointed Permanent Observer of the Holy See to the United Nations and, two weeks later, to the same post with the Organization of American States. His life in diplomatic service is laden with numerous and important commitments, but Msgr. Auza gladly took time to answer our questions about his experience in Haiti and his first few months of service as a Permanent Observer to the UN.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on September 15, the eve of the opening of the 69th session of the UN General Assembly, at a prayer service at the Church of the Holy Family in New York. Looking on is Father Gerald Murray, pastor of Holy Family Church; Archbishop Bernard Auza, the new papal nuncio to the United Nations; and Auxiliary Bishop Gerald Walsh of New York, archdiocesan vicar general.

Monsignor Auza, what went through your mind, what was your first reaction, when you found out you would become a permanent observer of the Holy See to the United Nations?

Archbishop Bernard Auza: My first reaction was to accept the will of the Holy Father in total obedience, even if it didn’t match my preference, in terms of my desired working commitments. After all, when I decided to become a priest, I was aware that I had also decided to obey the will of my bishop in particular, and of my ecclesiastical superiors in general. Everything I’ve done as a priest, I’ve done because I was told to do it. I came to Rome to study on my Bishop’s decision, and with the same spirit I have gladly accepted all of my appointments in 24 years of service to the Holy See, including this one. The acceptance of the appointment was “sweetened” by the fact that I already had an idea of the type of mission that was waiting for me in New York, because during the seven and a half years working at the Section for Relations with States of the Secretariat State I had had to deal with agencies and multilateral issues, and I had worked at this same Permanent Mission of the Holy See to the United Nations in New York from July 2006 until my appointment as Apostolic Nuncio to Haiti in May 2008.

About Haiti: when you became a UN Permanent Observer, you left Haiti. How can you sum up your years there, both in human and spiritual terms, amid such large-scale natural calamities?

Auza: My six years in Haiti were hard ones, due to the major disasters, particularly the earthquake of January 12th, 2010, and the cholera epidemic, the extreme poverty and the persistent institutional instability. But that period also gave me a great opportunity to engage in all kinds of spiritual and humanitarian work, as well as reconstruction projects. Material poverty taught me to be content with little. Due to the scarcity or absence of many basic services, such as running water and electricity, I learned to live with uncertainty. As a priest, I think I learned many things from the local Church. I tried to visit distant communities and remote villages, to administer the sacraments and to convey the Holy Father’s closeness to those who were, in every sense, the most distant, bringing his words of comfort to those who were suffering.

What picture did you get of the UN during your years spent serving around the world (and also in Rome)? Has this image been confirmed for you in your first few months as Permanent Observer?

Auza: I had contacts with several UN agencies in my traveling around the world, and I kept up on the activities of the United Nations even before I began working for the Secretariat of State, and in New York. I had formed the idea that it was an international institution whose primary mission was to prevent new wars and promote human rights. This mainly coincides with what is currently being done at the UN.

Many Catholics around the world see the UN in a negative light: they accuse it of not being able to prevent wars or stop aggression, and not being able to defend the victims. And, in another respect, the UN is accused of not always defending basic human rights, and of focusing more and more often on promoting the so-called “new rights.” Can you say something about this?

Auza: The observation that the UN has failed in its primary mission to prevent conflict and promote peace is, unfortunately, justified: we see it in the deterioration of the world’s situation in general, the resurgence of old conflicts, the persistence of today’s conflicts and the emergence of new forms of brutality and the fearsome contempt for basic human rights and humanitarian law. The UN’s inability to act in the face of barbarianism in northern Iraq is one example. Still, we must recognize that the UN peacekeeping missions in various areas of conflict and instability are a credit to the institution and to all its members and supporters. Unfortunately, the UN — or, more precisely, some of its stronger members who have specific objectives in mind — has also started promoting the so-called “new rights” and imposing compliance to these on other countries. Not infrequently, the Permanent Missions from poorer or smaller countries do not participate in negotiations on resolutions and other UN documents due to lack of staff or, some say, because they feel intimidated by certain more powerful and wealthy members. I just wish they could be more present in the negotiations, so that their voices could be heard and their values made known, so they could be defended.

Archbishop Auza when he was papal nuncio to Haiti, with Boston’s Cardinal Sean O’Malley, on March 2, 2010, during the US bishops’ first assessment tour of the island nation following the January 12 earthquake.

You have made many speeches in these first months: on October 29th, you made one on human rights, highlighting the importance of religious freedom, often violated in many countries of the world, as evidenced in the recent report of “Aid to the Church in Need.” Please satisfy our curiosity: you know “Aid to the Church in Need” very well, having been a recipient of one of their scholarships. Can you tell us something more?

Auza: I first met the ‘’Aid to the Church in Need” organization when I came to Rome in 1986 to study for my degree in theology. My bishop had sent me to Rome without any financial aid, telling me simply to send a request to “Aid to the Church in Need.” They granted me a scholarship. I needed to get ready to teach in our seminary (Tagbilaran, Philippines). In 1987 I was told to enter the Pontifical Ecclesiastical Academy, but “Aid” decided then to discontinue my scholarship. But, at the insistence of the then-President of the Academy, they changed their minds, and continued to sustain me until [I completed] my degree in theology and my licentiate in canon law in 1990. I will always be deeply grateful to them for their help. I had very strong working ties with them when I was with the Nunciature in Bulgaria, in Albania, and especially when I was Apostolic Nuncio to Haiti. “Aid to the Church in Need” is among the most prominent supporters of the Church in Haiti. I was very impressed by the dedication and spirituality of all of its staff.

We continue on to the matter of religious freedom …

Auza: It is paradoxical: on the one hand, there shouldn’t be any need for us to speak of religious freedom with such insistence and frequency, since it is a universal human right, inalienable and fundamental; on the other, it is one of the most violated and despised rights of our times. As the Holy Father said, there are many more martyrs today that in the first centuries before the Edict of Milan. Violations against the right to religious freedom don’t only take the form of martyrdom: there are many other forms of discrimination, too. The Holy See feels it has a duty to condemn these violations whoever the victims may be, whether Christians, Muslims, Jews, etc. The speeches I have made at the UN are also a response to the Holy Father’s heartfelt, worldwide appeal, made so that a broad mobilization of conscience may be undertaken in favor of persecuted Christians and of all those who are persecuted because of their religion and their faith.

In another speech, on October 23rd, you addressed the issue of fighting poverty in the world, using an intriguing metaphor: “Concrete cases of poverty tell us that the rising tide does not always lift all boats; often it only lifts the yachts, keeps a few boats afloat, sweeps away many and sinks the rest.” What did you mean by this example?

Auza: I was wondering how to express the reality of a system or an economic model that, while undoubtedly generating wealth, also produces a widening gap between rich and poor. Consider this: the “economic worth” of the richest man in the world today is equivalent to the “economic worth” of the 156 million individuals in the lowest part of the economic ladder. Declaring that “the rich get richer and the poor get poorer” is no longer enough to capture people’s attention, nor does it accurately describe today’s economic reality that has become increasingly complex.

I wanted primarily to call into question the idea that a favorable economic situation (the rising tide) benefits the economic situation of all (all the boats). What actually happens is that the benefits of an economic situation (more from a favorable one, and much less from a depressed one) are neither equal nor fair for everyone, nor do they reach everyone. Inevitably, there emerge inequalities and marginalization, and these are becoming more and more evident. Those already in possession of great wealth (yachts) earn more and more (they are raised by the rising tide), and so on, so that the poor who have less resources (financial and human resources, skills and know-how, or connections and political contacts), or none of these resources at all, are progressively marginalized and swept away by the system (the boats swept away and sunk, despite the rising tide). The only just action here is the intervention of national and international authorities to regulate and mitigate the adverse effects of such an economic system. An economic model that focuses only on maximizing profit, even if that means laying off workers or violating their rights, can never contribute to peace or promote sustainable development. We can’t ask for an economic system with equal benefits for everyone, because such a system could not exist. But we do need to foster an ethical system that promotes a more equitable distribution of benefits.

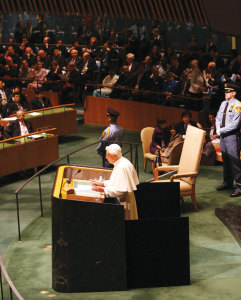

Pope Benedict XVI speaking at the UN.

In the Final Report (Relatio Synodi) of the recent extraordinary Synod on the Family, in Paragraph 56 we read: “Exerting pressure in this regard (editor’s note: regarding the matter of “homosexual ‘unions’”) on the Pastors of the Church is totally unacceptable: this is equally so for international organizations who link their financial assistance to poorer countries with the introduction of laws which establish ‘marriage’ between persons of the same sex.” Are you aware of this situation in your diplomatic activity? What can be done by the UN to prevent certain Western nations from using economic blackmail to push for “new rights” in countries of the developing world?

Auza: The Permanent Representative of an African country told me: “The Europeans brought us God; now they are asking us to abandon Him.”

When a diplomat from a poor or small country says he or she feels “intimidated” by rich and powerful countries that are pushing for the acceptance of so-called “new rights,” I am reminded of the pressures and unwritten conditions connected to international aid. Not infrequently, pressures and “compliance” are not explicitly expressed in the documents. They are carried out by agencies, commissions, or by individuals who, when sent to monitor the observance of the Conventions, interpret them in ideological and political manners. This is even more worrisome when such agencies or individuals require small and poor countries to apply certain Resolutions that in reality are not binding on anyone.

Sometimes you hear people say the UN is a useless body and should be abolished. What can you tell us about that? Can the UN’s decision-making mechanisms really be reformed? If so, in what direction?

Auza: I believe that the UN still remains the guardian of the ideals of peace and brotherhood of all peoples. It has its flaws, big and small, but it remains an international body of which all countries of the world are members, and remains a valid forum for discussing the problems facing the human family and the family of nations. The issue of UN reform is always very timely, especially the reform of the Security Council, which can be considered the keystone of real reform of the UN system.

Finally, the four visits to the UN made by three Popes — Paul VI on October 4th, 1965; John Paul II on October 2nd, 1979 and October 5th, 1995; and Benedict XVI, on April 18th, 2008 — had the purpose, as Paul VI said, of “a moral and solemn ratification of this lofty institution,” to express our belief that the UN “represents the necessary path of modern civilization and world peace.”

I believe that these words of Blessed Paul VI are proving themselves to be more prophetic than ever today, in a time when humanity is facing great uncertainty. The gravity of the moment called for the UN to make bold decisions.

Facebook Comments