Their common thread: “Christianity is a love story”

By Paschal M. Corby*

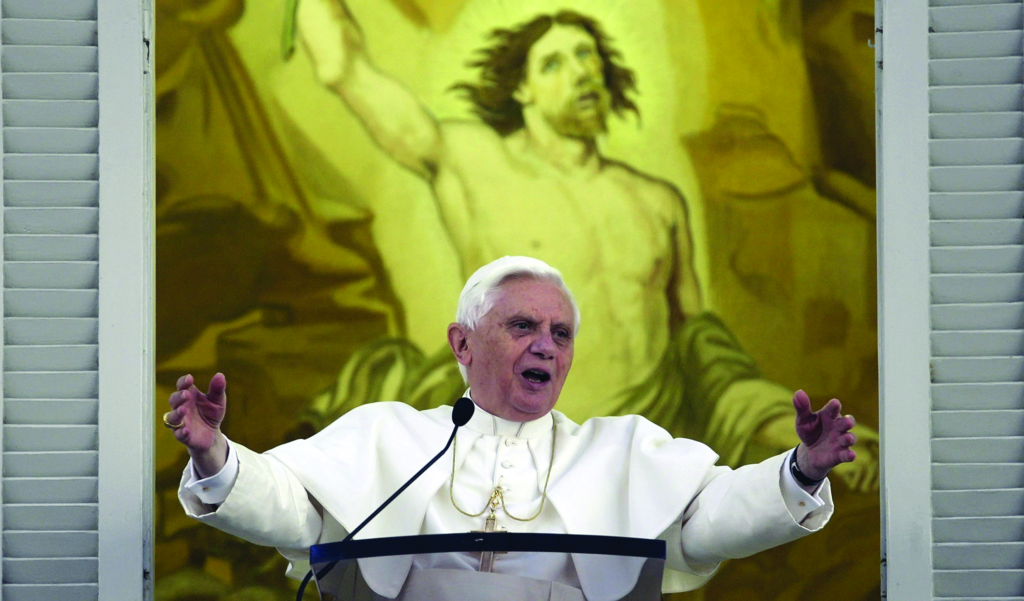

Pope Benedict XVI greets people from the balcony of his summer residence in Castel Gandolfo, Italy, Aug. 19, 2007. (CNS photo/Tony Gentile, Reuters)

In popular opinion, a Pope’s first encyclical heralds the tone of his pontificate. In the case of Benedict XVI, Deus caritas est, promulgated within a year of his 2005 election to the Chair of Peter, not only sets the tenor of his pontificate, but also crowns his long years of theological reflection. At the beginning of the encyclical we read: “We have come to believe in God’s love: in these words the Christian can express the fundamental decision of his life. Being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction” (DCE, 1).

Here, Benedict is reiterating a familiar theme. The Christian faith is not a philosophy or idea. Rather, it is a person. In his funeral homily for Luigi Giussani, Benedict had previously reflected that “Christianity is not an intellectual system, a collection of dogmas, or moralism. Christianity is instead an encounter, a love story; it is an event.”[1]

The encounter with Christ — speaking to us in the Gospels, substantially present in the Sacraments, abiding in His Church — not only establishes us as Christians, but reveals to us the truth of our being. And it is precisely this truth of our being that is the unifying principle of Benedict’s thought. The manifestation of God’s love in Jesus Christ reveals to us the uniqueness of our human nature as made for love – created in the image of God who reveals Himself as a Trinity of Persons.

The encounter with Christ further awakens us to our capacity for transcendence. That which is innate to human nature — the dissatisfaction with our lot, and a yearning for immortality — finds both its object and its hope in the risen Christ.

“Being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with.. a person, which gives life a new horizon”

(Deus Caritas Est, 1)

In Christ, the promise of a future is radically transformed. As Benedict had previously written, the focus of Christian hope “is not space and time, the question of ‘Where?’ and ‘When?’, but relationship with Christ’s person and longing for him to come close.”[2]

Immortal life does not consist in an extension of the experiences of this life, but in a personal communion of love with God in Jesus Christ.

Through an encounter with Christ we discover what true life is (cf. John 14:6), and our yearning for eternity is awakened. This is the basis of Benedict’s fundamental claim in Spe salvi that “to come to know God — the true God — means to receive hope” (Spe Salvi, 3; cf. Eph 2:12). In the wake of the nihilism and hopelessness of atheistic philosophies, as well as the deceptive hopes of technology and science, Spe salvi proclaims an order that is genuinely hopeful. Benedict writes: “It is not the elemental spirits of the universe, the laws of matter, which ultimately govern the world and mankind, but a personal God governs the stars, that is, the universe; it is not the laws of matter and of evolution that have the final say, but reason, will, love—a Person” (SS, 5). Or again: “It is not science that redeems man: man is redeemed by love” (SS, 26). Hope, therefore, is based on something beyond ourselves. But this something is personal. It is ‘Someone’, and he reveals himself to us as love.

The intimate connection between hope and love coincides with Benedict’s fundamental premise that love always promises something more, that love is redemptive (SS, 26), and that eternal life “would be like plunging into the ocean of infinite love” (SS, 12). As Benedict had written previously, “the hope which transcends all hopes is the assurance of being showered with the gift of a great love.”[3] That we experience love now is the foundation of our hope. It is in this sense that hope ‘saves’ us, offering us the “certainty that I shall receive that great love that is indestructible and that I am already loved with this love here and now.”[4]

Finally, it is through the encounter with Christ, the God-man, who inspires love and hope in the human heart, that we perceive the truth of the human person. He reveals what is good for man, and becomes the icon of human fulfilment. True human development, therefore, finds its source and logic in Christ, and this is the concern of Benedict’s final encyclical, Caritas in veritate. As the title suggests, Benedict insists on maintaining the deep connection between love and truth. “To defend the truth, to articulate it with humility and conviction, and to bear witness to it in life are therefore exacting and indispensable forms of charity” (CV, 1).

In establishing his concern for authentic human development, Benedict draws his three encyclicals together: “Love is God’s greatest gift to humanity, it is his promise and our hope” (CV, 2). True development can only occur when the truth of the human person is respected; when the individual person, with his or her fundamental rights and dignity, are upheld. Thus, there can be no development where life is not respected. In this Benedict is insistent: “If there is a lack of respect for the right to life and to a natural death, if human conception, gestation and birth are made artificial, if human embryos are sacrificed to research, the conscience of society ends up losing the concept of human ecology” (CV, 51).

Again, he insists that true development cannot simply come by way of advances in technology, but by means of a human mind, heart, and conscience that knows how to act according to what is true and good. With his characteristic critique of contemporary culture, he warns that advances in practical knowledge are “not matched by ethical interaction of consciences and minds that would give rise to truly human development.” He counsels that “only in charity, illumined by the light of reason and faith, is it possible to pursue development goals that possess a more humane and humanizing value.” It is not technical progress and utility that ensures equality and integral development, but “the potential of love that overcomes evil with good” (CV, 9).

This is reminiscent of a theme within Deus caritas est, in which Benedict warns that, while technical skill is essential in many works of charity, “human beings always need something more than technically proper care. They need humanity. They need heartfelt concern” (DCE, 31). Thus, in addition to the professional competence that is essential to any service, Benedict speaks of the need for a “formation of the heart”; of “a heart which sees”, that perceives “where love is needed and acts accordingly” (DCE, 31).

And again, such can only happen through an “encounter with God in Christ which awakens their love and opens their spirits to others” (DCE, 31). “Seeing with the eyes of Christ, I can give to others much more than their outward necessities; I can give them the look of love which they crave” (DCE, 18).

As Benedict insists, it is only at the level of encounter that the true needs of the human person can be met. Governments and organizations are no substitute for personal presence. When they attempt to do so – when the State seeks to provide for every need – the result is the elimination of man. “Love—caritas—will always prove necessary, even in the most just society” (DCE, 28). This coincides with Benedict’s preferential option for the principle of subsidiarity as expressed in Caritas in veritate. “A particular manifestation of charity and a guiding criterion for fraternal cooperation … is undoubtedly the principle of subsidiarity, an expression of inalienable human freedom.”

According to Benedict, subsidiarity fosters autonomy and responsibility. “Subsidiarity respects personal dignity by recognizing in the person a subject who is always capable of giving something to others” (CV, 57). It therefore accords with the nature of the human person as ordered towards gift and love.

The genius of Benedict XVI is his capacity to enter into the heart of man. He knows of what we are made, and for what we are made.

His encyclicals, the fruit of years of theological reflection, are testimony to this deep knowledge of man, who is fully revealed only in the person of Christ — in whom we encounter God, and who is the way, the truth, and the life (Jn 14:6).

*Rev. Dr. Paschal M. Corby, OFM Conv., MBBS, BTheol, STL, STD, is a priest of the Order of Friars Minor Conventual and assistant priest of the Parish of St. Joseph’s, Springvale, Australia. He currently lectures in Moral Theology/Bioethics at the University of Notre Dame, Australia (Sydney) and Catholic Theological College (Melbourne). He is the author of The Hope and Despair of Human Bioenhancement (Pickwick, 2019).

[1] Joseph Ratzinger, “Funeral Homily for Msgr. Luigi Giussani,” Communio 31 (2004).685.

[2] Joseph Ratzinger, Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life (Washington DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1988), 8.

[3] Ratzinger, “On Hope,” Communio 35 (2008), 303.

[4] Joseph Ratzinger, The Yes of Jesus Christ: Spiritual Exercises in Faith, Hope and Love (New York: Crossroad, 1991), 70.

Facebook Comments