Bacci described human life in an ancient, sacred language — and then blessed it

By John Byron Kuhner*

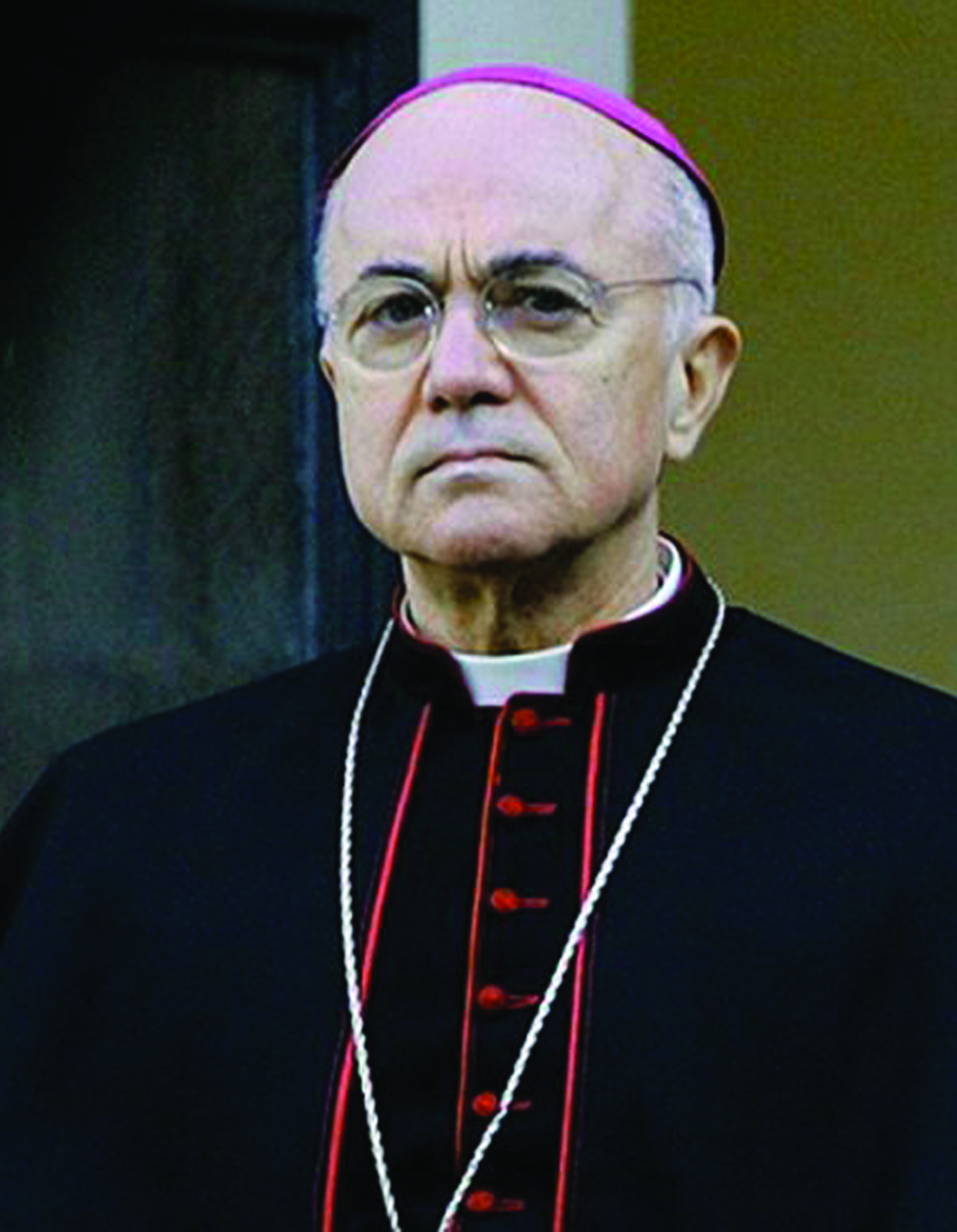

In my last Latin column, I wrote about the late Antonio Cardinal Bacci, who served as one of the two papal Latin secretaries from 1931 until his elevation to the cardinalate in 1960. Bacci’s love of his cardinalatial regalia drew the ire of a 1960s critic who wrote on his Vatican-issued Mercedes-Benz (the preferred vehicle of cardinals) “RECEPISTI MERCEDEM TUAM.” It’s one of the greatest puns in Latin history. On the face of it, the line means “you have received your Mercedes,” but it can also mean “you have received your reward,” the warning Jesus gives when he tells the rich not to expect anything good in the next life. If any of us found that soaped onto our cars, we’d do well to take it as a sober reminder of God’s majesty, compared with which none of our good deeds can ever seem impressive. But I would feel remiss if the only account I gave of the great papal Latinist was the time he was on the receiving end of a perfectly executed pasquinade. Bacci was a remarkable Latinist, and careful examination of his Latin works shows him to be a generous, thoughtful, and humane man — one whose example is well worth contemplating.

In my last Latin column, I wrote about the late Antonio Cardinal Bacci, who served as one of the two papal Latin secretaries from 1931 until his elevation to the cardinalate in 1960. Bacci’s love of his cardinalatial regalia drew the ire of a 1960s critic who wrote on his Vatican-issued Mercedes-Benz (the preferred vehicle of cardinals) “RECEPISTI MERCEDEM TUAM.” It’s one of the greatest puns in Latin history. On the face of it, the line means “you have received your Mercedes,” but it can also mean “you have received your reward,” the warning Jesus gives when he tells the rich not to expect anything good in the next life. If any of us found that soaped onto our cars, we’d do well to take it as a sober reminder of God’s majesty, compared with which none of our good deeds can ever seem impressive. But I would feel remiss if the only account I gave of the great papal Latinist was the time he was on the receiving end of a perfectly executed pasquinade. Bacci was a remarkable Latinist, and careful examination of his Latin works shows him to be a generous, thoughtful, and humane man — one whose example is well worth contemplating.

Many of the highlights of Bacci’s Latin career can be found in his Inscriptiones Orationes Epistulae (1944), a collection of his inscriptions, speeches, and letters. Its dry title does not sound very promising, and I can’t say it ever became a bestseller, but it went through three editions in 11 years after its first publication in 1944 by the Libreria Editrice Vaticana, a respectable showing for a book entirely in Latin.

Why did it find any readers? Well, for one thing, the book comes from inside the Vatican, where history is made.

Bacci gave the ellogium, the funeral oration containing a summary of the pontiff’s life and career, spoken over the body of the dead Pope and placed inside his coffin, for Pius XI (and later for Pius XII). You can also find his speech to the College of Cardinals just before the 1939 conclave, when Italy, Germany, and Japan had invaded multiple countries already and were agitating for more bloodshed. Countless inscriptions belong to the actual war years, and so they show how the Church positioned herself, as the Second World War actually progressed, as a public opponent of war and bloodshed, which are consistently described as horrors. Bacci composed the public inscriptions of the later years of Pius XII’s pontificate, when the Church was growing and confident. These are valuable historical documents.

But most remarkable is the humanity that Bacci’s inscriptions capture.

There is an inscription for a tiny brother of his, an infant who died an hour after birth, and for a sister who left this world at the age of 17, dum ex autumnalibus arboribus stillantia folia cadebant, “as the dropping leaves fell from the autumn trees.”

There are epitaphs for his father and mother and for friends, including one for his eye doctor, praising his neardivine gift of improving people’s vision.

There are inscriptions celebrating gyms and motorbikes and the Vatican radio tower. There are several which celebrate matrimony in elegant terms. I might well consider putting this one up in my home:

AMOENA HAEC VILLULA

HILARO CIRCUMSAEPTA VIRIDARIO

IVCVNDA NOBIS SEDES ESTO

EX EADEMQVE

VELVTI GARRVLAE EX NIDVLO AVES

PVELLVLI ALIQVANDO EGREDIANTVR

QVI LAETITIAM CVMVLENT

NOSTRAM

“May this pleasant little retreat, enclosed in a lovely garden, be a happy seat for us, and from the same, like peeping birds from their little nest, may little children someday come forth to add to our happiness.”

Bacci seemed to want to stick Latin onto just about everything. There is an inscription for a wallet:

NVMMATVM QVO FRVERIS

MARSVPIVM

SIT NVMQVAM EGENTIBVS CLAVSVM

MEMENTO NON TE PECVNIAE

SED PECVNIAM TVI ESSE MANCIPIVM

AC SORDIDIS AVARIS

NIHIL VALERE

AVRVM

“May this monied wallet you enjoy never be closed to the needy. Remember that money is not your master but your servant, and that gold profits the dirty miser not at all.”

Bacci’s work reads like a series of Latin poems, much like the Roman poet Martial, who wrote epigrams on a wide variety of topics at the height of Roman Imperial days.

But while Martial was a ferocious satirist out to mock people — for their greed, their sexual proclivities, or their baldness — Bacci’s work seems fundamentally priestly: his task is, through the medium of an ancient, sacred language, first to describe and understand human life, and then to bless it.

He knows that many aspects of human life can be, unless connected to a deeper pattern of divine meaning, disappointing, but that does not hinder his blessing.

Such is another of his inscriptions about marriage:

AMORE

DVLCITER TEMPVS ELABITVR

TEMPORE

PEDETEMPTIM DILABITVR AMOR

SED DIVINA CARITAS

QVAE NOSTRVM SACRAVIT CONIVGIVM

PERPETVO MANET

MAGISQVE COTIDIE EVEHITVR

“With love time slips sweetly by; with time love slowly slips away; but the divine charity which has sanctified our marriage remains forever, and each day grows even more.”

It is amazing how many topics Bacci manages to touch on in his book: there is a prose-poem about the glories and comforts of indoor plumbing, and one about Pius XII’s restoration of the Loggia painted by Raphael at the Vatican; information about the mid-20th century strengthening of Michelangelo’s dome in St. Peter’s and a celebration of a literal henhouse (gallinaria). There are records of buildings destroyed by bombs during the war and an appreciation of his own little home library, with its books and chairs.

For those who know Latin, Bacci’s little volume of inscriptions is a real delight: it is a quiet testimonial to the man’s deep appreciation for God’s creation, and a statement of his profound belief that only God can truly redeem it.

*John Byron Kuhner is the editor of the Paideia Institute’s online journal In Medias Res, and is working on a biography of the great papal Latinist Fr. Reginald Foster.

Facebook Comments