Cardinal Bacci Gets His Mercedes

By John Byron Kuhner*

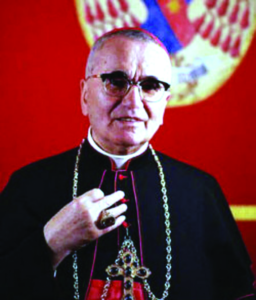

Here, Cardinal Antonio Bacci (1885 1971), one of the great Latinists in the Roman Curia

For a picture of the world of Latin at the Vatican in the not-so-distant past, you can hardly do better than to investigate the works of Cardinal Antonio Bacci. His memoirs are a great place to start. Entitled Con il Latino a Servizio di Quattro Papi and published in 1964, it was translated into English by Anthony Lo Bello as With Latin in the Service of the Popes, published first by the Latin LiturgyAssociation and now by Arouca Press. Bacci was born in 1885, in the days of Leo XIII, and died in 1971, after watching — to his great sorrow — Latin driven from the vast majority of the altars, seminaries, and monasteries of the Church.

Bacci came to work in the Vatican’s Latin office in 1922, at the age of 37. He was teaching in the seminary of Florence at the time, and describes being called aside from a class he held outdoors one morning by the cardinal-archbishop of Florence, who told him to come see him at eleven o’clock and added somewhat ominously, “Habeo aliquid tibi dicere” — “I have something to say to you.”

I then went to the Cardinal’s apartment and had myself announced. He received me paternally, as he always did, and invited me to sit down. Then he began, “You know that today, September 30, is the feast of St. Jerome, who was the Latin secretary of Pope Damasus. The people at Rome have asked me for a Latinist, and I thought that you were just the right man to send, so you will go to the Secretariat of State as Latinist; then, later on… who knows?” At these words, I was astounded, and could not express anything but thanks and obedience.

The “later on… who knows?” is a sign of the importance of the Latin office at this time in history. Indeed, before Vatican II, the Latin office was a road to high preferment in the Church: to rise to the position of one of the two Latin secretaries to the Pope assured an eventual promotion to the cardinalate. To be sent to the Latin office in one’s 30s was to be put on track to become one of the princes of the Church.

Bacci began as a mere junior Latinist in the office but was made full Latin secretary nine years later when he was elevated to the title of Secretarius Brevium ad Principes, Secretary of Briefs to Princes.

But already the Church was changing, and Latin was losing its importance. Bacci would wait almost 30 more years to get his red hat, which he received from John XXIII in 1960 when he was 75 years of age.

The following story about Bacci is most assuredly not found in his memoirs, but is one of the legends I heard about him while I was a student in Rome; and se non è vero, è ben trovato, as the Italians say — loosely translated, “if it isn’t true, it should be.”

Bacci’s book, translated into English by Anthony Lo Bello as With Latin in the Service of the Popes, published first by the Latin Liturgy Association and now by Arouca Press

As far as I know, this is the first time this story is appearing in print, though perhaps my readers will correct me.

In Rome, at the time it was widely bruited about that Bacci had long been exasperated about his long-delayed promotion, and once he got it, he made sure to be seen around Rome in his new cardinalian regalia. We’re all familiar with the black cassock with scarlet piping, the scarlet biretta, the scarlet fascia (that sash), and perhaps even the scarlet socks of a cardinal. But more visible on the streets of Rome is the fact that cardinals traditionally ride in Mercedes-Benz automobiles (the Popemobile is traditionally a Mercedes as well). Well, Bacci showed up one day to the Gregorian University with his chauffeur and Mercedes to transact some business. It was the 1960s, and the students at the “Greg” were seminarians but they had caught the spirit of the 60s just like anyone else, engaging in lively debates as to whether or not the traditional trappings of Church life really were compatible with the Gospels. And so someone went over to Bacci’s Mercedes with a bar of soap to make a political theological point. When the cardinal returned to his car, he found soaped onto it the Latin phrase, RECEPISTI MERCEDEM TUAM. In the context, it would be the way you would say in Latin, “You have received your Mercedes.”

A typical Mercedes used in the 1960s by Church authorities

But it’s a much larger, more ingenious theological comment. The word “mercedem” in Latin means “reward,” and it’s a word commonly found in the Bible. Indeed the soaped message is an adapted line from the Gospels when Jesus tells us to do our good works and to pray unbeknown to others: “So when you give alms, do not have a trumpet playing before you, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and the streets, so that they may be honored by people; Amen, Isay to you, they have already received their reward (receperunt mercedem suam).” (Matthew 6:2).

Cardinal Antonio Bacci’s coat of arms. His motto was “Non nomen sed virtus” — “Not the name but the virtue”

Or, in this context, they have already received their Mercedes. The comment throws some good Gospel shade on the people jockeying for preferment in the Church, with all its attendant perks (“scarlet fever,” the wags of Rome call it). The Gospel calls us to something deeper. This is not to cast aspersions on the character of Bacci himself, who in his writings shows himself as a generous, caring human being (I will go into further detail in my next column). But insofar as he was ambitious, he may well have merited this pasquinade. And one way or another, it’s a great example of the kind of theological richness you can get from a continual linguistic tradition: because the Gospels are so central to Church Latin, even a simple comment — “you got your Mercedes!” — carries with it a whole host of theological questions about the relationship of our enjoyment of the good things of this world to our eternal salvation. It serves as a continual reminder of the spiritual in this world.

*John Byron Kuhner is the editor of the Paideia Institute’s online journal In Medias Res and is working on a biography of papal Latinist Fr. Reginald Foster.

Facebook Comments