“The law says, ‘Hear, Israel’… It did not say, ‘Speak'”

By John Byron Kuhner

Sts. Augustine and Ambrose, by Filippo Lippi, Albertina Academy of Fine Arts, Turin, Italy

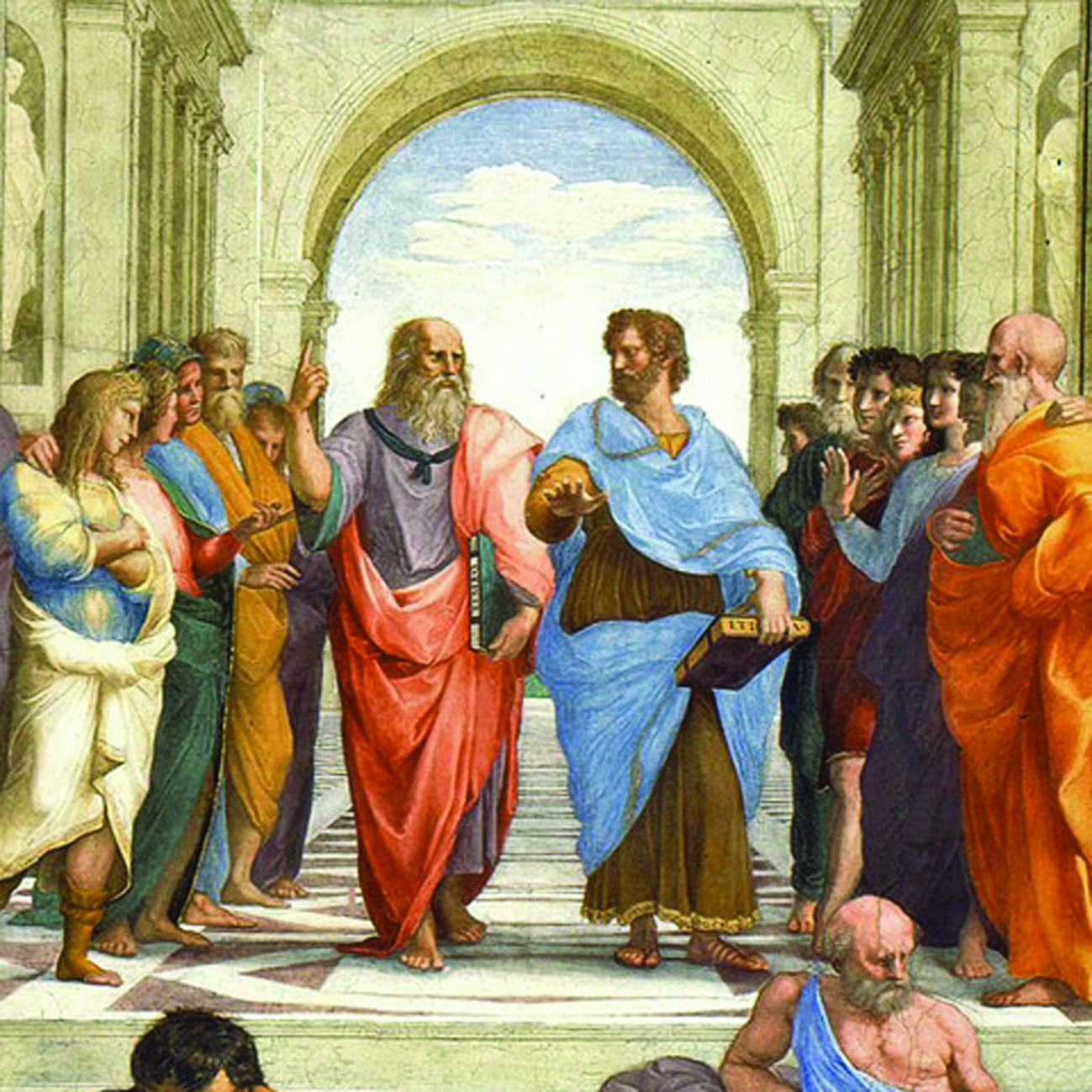

If you were to write an ethical guide for life, where would you start? What do you think would be the starting place for understanding how to live a moral life? The philosopher Aristotle began his Nicomachean Ethics by discussing what the ultimate end of human life is. Cicero the orator, in his De Officiis (“On Duties”) started by attempting to give a definition for moral duty. St. Ambrose, the great doctor of the Church, started in a completely different way. He believed that the starting place for the Christian ethical life is silence.

Quid aliud prae ceteris debemus discere quam tacere? Ambrose says after a brief preface in his own De Officiis. “Before the rest, what thing should we learn, other than to be silent?” He reiterates his point over and over, providing the later Church with an arsenal of one-liners about the place of silence in the Christian life. Sapiens est qui novit tacere. “The wise man is he who knows how to be silent.” Sancti Domini… amabant tacere. “The saints of the Lord were in love with silence.” He quotes the Law: Lex dicit: ‘Audi, Israel, Dominum Deum tuum.’ Non dixit, ‘Loquere,’ sed ‘audi.’ “The Law says: ‘Hear, Israel, the Lord your God.’ It did not say, ‘Speak,’ but ‘hear.’” He quotes the Psalms: Dixi, ‘Custodiam vias meas, ut non delinquam in lingua mea.’ “I have said, ‘I will have custody of my ways, that I may not fall by my tongue.’” He sums it up: Prima vox Dei dicit tibi: ‘Audi.’… Tace ergo prius, et audi. “The first voice of the Lord says to you: ‘Hear.’” … Therefore be silent, and hear.”

He refines this later, and notes that there is a time to speak as well (quoting the famous “a time to” passage from Ecclesiastes), but there is no doubt that Ambrose is expressing an entirely different kind of worldview from Aristotle and Cicero. They believed in expertise, and wanted their students to intellectually grasp the entirety of a defined subject known as ethics. Ambrose is naming silence as the first step in a spiritual practice, rooted not in expertise but in awakening the richness of the inner life by first stilling the endless torrent of words.

Plato and Aristotle in The School of Athens by Raphael

Ambrose writes in Latin, but the inner life of his prose is not like Cicero’s and not like Aristotle’s. Possessio tua mens tua est, aurum tuum cor tuum est, he writes. “Your inheritance is your mind, your gold is your heart,” he writes. Cicero never wrote like this. Custodi interiorem hominem tuum. Noli eum quasi vilem negligere ac fastidire, quia pretiosa possessio est. Et merito pretiosa, cuius fructus non caducus et temporalis, sed stabilis atque aeternae salutis est. Cole ergo possessionem tuam, ut sint tibi agri. “Guard your inner person. Do not neglect it like a mean thing and despise it, for it is an inheritance of great price. And justly is it of great price, whose fruit is not fleeting and temporal, but lasting and of eternal salvation. Cultivate, therefore, your inheritance, as it were your fields.”

Interestingly enough, we have an eyewitness account of St. Ambrose, and the thing which the witness describes as the most striking thing about him is… his silence!

The witness was none other than St. Augustine, who saw St. Ambrose as an important figure in his conversion, and had the chance to meet the great bishop of Milan:

Sed cum legebat, oculi ducebantur per paginas et cor intellectum rimabatur, vox autem et lingua quiescebant. Saepe, cum adessemus – non enim vetabatur quisquam ingredi aut ei venientem nuntiari mos erat – sic eum legentem vidimus tacite, et aliter numquam, sedentesque in diuturno silentio – quis enim tam intento esse oneri auderet? – discedebamus.

“But when he read, his eyes were led along the page and his heart would search out the meaning, but his voice and tongue were silent. Often, when we were present – no one was prohibited from coming to see him, nor was it his custom to have visitors announced – we saw him reading silently; we never saw him reading otherwise, and sitting in long silence – for who would dare to be a burden to a person so intent? – we would leave.”

Cicero during his oration against Catiline for conspiracy against the Roman Republic

The passage has elicited much comment. Did Augustine mean to say that he had never seen anyone read silently before? Was all reading done aloud at the time? The passage seems to suggest this.

However one may interpret it, there was something particularly majestic about Ambrose’s silence. His silence meant something; there was a presence in it. It awed Augustine; he was unwilling to break such a silence with his words.

St. Ambrose’s feast is December 7, not the day of his birth nor that of his death, but of his ordination as bishop of Milan. His particular place in Church history is as a bishop. Indeed, in the Western Church, he is in certain ways the archetypal bishop. In that role, he is known for his openness to people, his constant work, and his great generosity to the poor. Yet he is also known for a kind of majesty, a greatness in his role that made him the equal of Roman emperors. I have no doubt that he told us the key to this majesty: that he had first long practiced the art of silence.

When I meet people of great spiritual power, their silence has this kind of majesty. It should be the first thing we look for in a bishop, from the smallest see to the See of St. Peter himself.

Facebook Comments