By Thomas Storck

As many globalists began to speak of the need for a “Great Reset,” Pope Francis met with a group of leading capitalists on November 11, 2019, to create a global “Council for Inclusive Capitalism.” What is it all about? What is the Pope’s role? Where in all this is the salvation brought by Jesus Christ?

Veteran Vatican watchers might have been puzzled by the December 8 announcement (on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception) that Pope Francis had met with and endorsed members of something called the “Council for Inclusive Capitalism.” Reactions to this have varied. Some have seen this as a continuation of the Church’s long-time interest in promoting a more just economy. Others, more extreme, see it as a conspiracy on the part of those who hold sway over the world’s economy.

“If we accept that the great principle that there are rights born of our inalienable human dignity, we can rise to the challenge of envisioning a new humanity. We can aspire to a world that provides land, housing and work for all.” -Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti, 2020 encyclical on fraternity and friendship

First, what is this organization and what is it trying to do? The Council for Inclusive Capitalism is connected to its parent organization called the Coalition for Inclusive Capitalism. Its aims as listed on its website are the following: “The Coalition for Inclusive Capitalism is a global non-profit organization that works with leaders across the private, public and civic sectors to make capitalism and its benefits more widely and equitably shared. Our mission is to advance the global movement to make economic systems more inclusive, sustainable, strong and trusted.”

The Council is characterized as the Coalition’s “sister non-profit, a historic collaboration of CEOs and global leaders working with the moral authority of Pope Francis and Cardinal Peter Turkson… to harness the private sector to create a capitalism that is more fair, inclusive, and sustainable.”

It seems that the Coalition and the Council are really the same entity, the latter merely the name used when it works with the Vatican. In fact, the websites of the two organizations are so intertwined that sometimes it’s hard to know, without looking at the web address (URL), whether the webpage on the screen is from the Council or the Coalition.

The Council’s own aims, as presented on its webpage, pro-claim: “Our mission is to harness the private sector to create a more inclusive, sustainable, and trusted economic system. Capitalism lifts people out of poverty and powers global innovation and growth. But to address the challenges of the 21st century, capitalism needs to adapt. Through our commitments, actions and solutions, we will create stronger, fairer, more collaborative economies and societies, ultimately improving the lives of countless millions of people across the globe.”

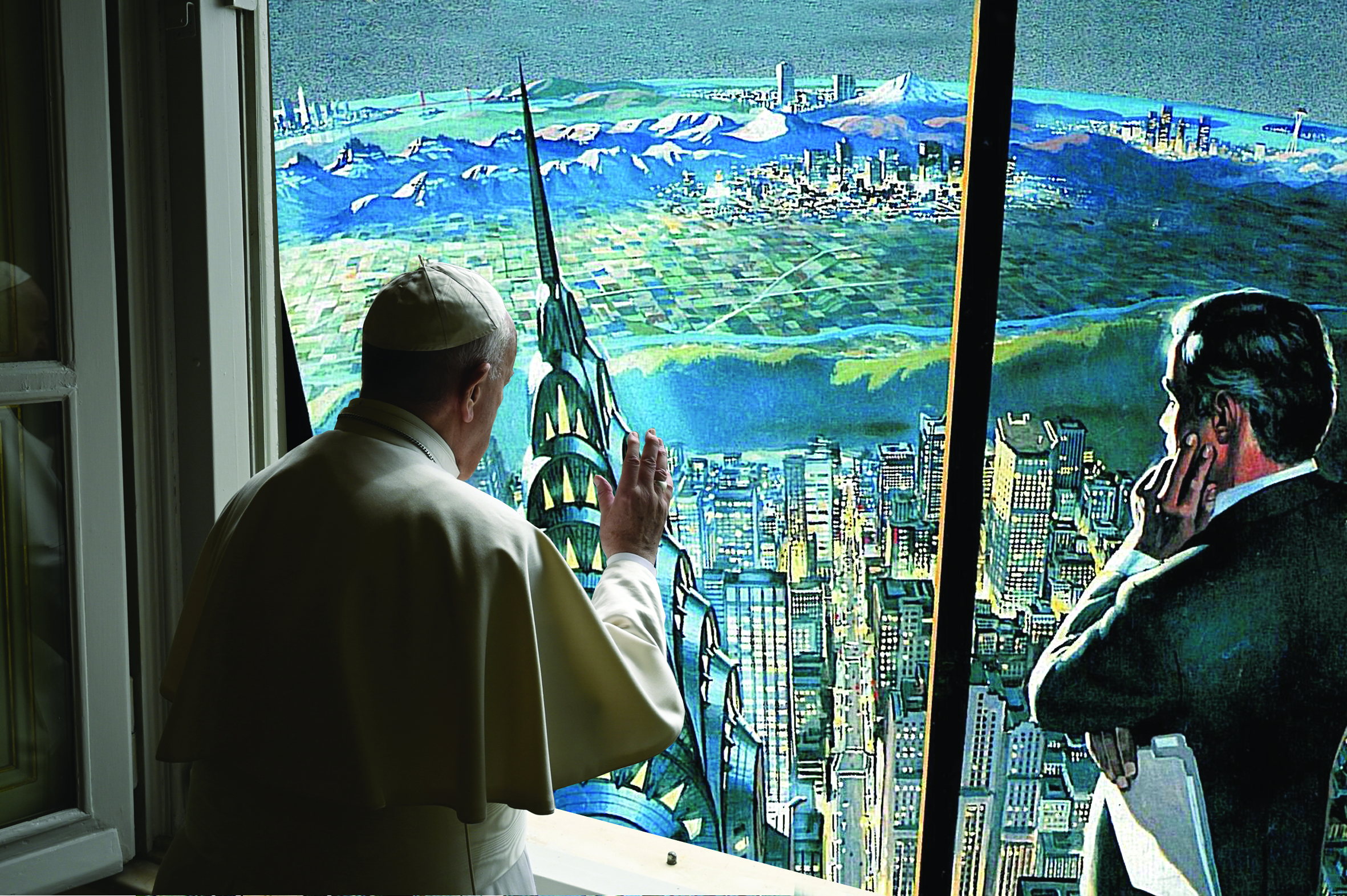

Although news reports stated that the Council “launched a partnership with the Vatican” on December 8, 2020, actually the Vatican’s formal involvement with the Council appears to have begun in 2019 when Pope Francis met with its members on November 11. In his address at the time, Francis noted that in 2016 he had spoken to the participants in the Fortune-Time Global Forum on “the need for more inclusive and equitable economic models that would permit each person to share in the resources of the world.” The Council, he stated, “is one of the results of the 2016 Forum.”

However, according to a 2014 article in the English newspaper The Guardian, the Council is really the result of a meeting held in London “hosted by the City of London Corporation and E L Rothschild investment firm” in May of 2014. It, in turn, was “the brainchild of the Henry Jackson Society, a little-known but influential British think tank.” According to this source, its aim all along was primarily cosmetic. Because of a fear that there was such“public disgust with the system, there was a very real danger that politicians would seek to remedy the situation by legislating capitalism out of business,” the leaders of international finance and business felt the need to take steps to change the public perception of international capitalism.

“Capitalism has created enormous global prosperity, but it has also left too many people behind, led to degradation of our planet, and is not widely trusted in society.” — Lynn Forester de Rothschild, founder of the Council for Inclusive Capitalism

The article quotes Lady Lynn Forester de Rothschild, co-host of the 2014 meeting: “I think that a lot of kids have neither money nor hope, and that’s really bad. Because then they’re going to get mad at America. What our hope is for this initiative, is that through all the efforts of all of the decent CEOs, all the decent kids without a job feel optimistic.” [emphasis in source]

According to this interpretation, then, the entire effort is little more than a public relations gimmick to make people less likely to get angry on account of their unemployment or poverty.

Who is Lady Lynn Forester de Rothschild? She is the wife of Sir Evelyn de Rothschild, member of the legendary Rothschild banking family. She and her husband are reputed to have a personal fortune of around $20 billion. The reputation Pope Francis has in many circles is that he would be the last person to associate with international bankers of that sort. After all, is he not the same pontiff who criticized in Evangelii Gaudium the fact that “the earnings of a minority are growing exponentially[and] so too is the gap separating the majority from the prosperity enjoyed by those happy few,” and who rejected“the absolute autonomy of markets and financial speculation”?

But however this may be, if we look at the roster of Council members, divided into three categories strangely labeled Guardians, Stewards and Allies, one sees the names of CEOs, directors or other officials of such companies or entities as Mastercard, DuPont, Merck, Estée Lauder, Johnson& Johnson, VISA, BP (British Petroleum), Bank of America, the Rockefeller Foundation, and many more—in short, many of the richest people in the world, people who, hitherto at least, have profited quite well on account of “the absolute autonomy of markets and financial speculation.”

So is this merely a gimmick, as The Guardian has charged? What is the Council or the Coalition actually supposed to do?

They have issued a Framework which includes a number of measures that are certainly in accord with Catholic social teaching, including such proposals and suggestions greater worker safety protection on the job, that “technological change does not have to lead to job loss,” infrastructure funding, giving “workers a stronger voice in the corporation,” that “the minimum wage should be raised to be a living wage, not a starvation wage,” that “corporate bankruptcy law should be amended to prioritize workers’ retirement plans over other corporate debts to prevent employers from shedding their obligations,” and so on.

Most of the specific proposals made in this Framework are certainly ones that a Catholic can support. Although many of them could be implemented immediately on the part of corporation without any government mandate,most of them call upon governments to undertake legal and policy reforms in order to carry them out.

But other of the actions suggested are perhaps open to question. In a long list of Commitments (actions that individual members have committed to do), we find the following: “Capdesia [an investment firm focusing on European food suppliers] commits to ensuring that 100% of its restaurant portfolio companies and their suppliers produce and/or deliver safe, high quality, nutritious, great tasting and sustainable foods to their customers.”

Whew! One is surely relieved that no longer will Capdesia work with companies providing tasteless junk food.

But really, this is little more than one reads in corporate promotional material touting how wonderful a particular company is.

Other commitments sound like mere vapid “corporate-speak.” For example: “DuPont will improve the lives of over 100 million people in communities worldwide by 2030, expanding our social impact through signature partnerships, establishing regional advisory councils, and investing in environmental and community impact.”

Or this choice example: “Simfoni [a supplier of automation products] will identify and report on place-based impact metrics rooted in the lived experience of people by the end of 2025 and incorporate these across 100% of projects.”

More seriously, though, many of these Commitments are to increase diversity in “gender” and other categories.

Given the fluid and politically correct usage of many such terms today, it is impossible to know what will actually be implemented and whether they are good, bad, neutral or just silly.

And if they are implemented, if say, Beleap, a consulting firm, does succeed in promoting “women to at least 30% of leadership positions by 2023,” will that actually improve the lives of the poor or result in a more just economy?

So, what are we to think of all this? While some critics have claimed to see in it a thinly-veiled socialism, and others think they discern a conspiracy on the part of the Rothschilds and others who are long suspected in certain quarters of really running the world from behind the scenes, both these explanations seem rather unlikely. But still one might question the initiative on any number of grounds.

“… And so, therefore, if you ask what our hopes are, we don’t have any prescriptions. We are also following what Benedict XVI taught about the need for dialogue between faith and reason, all kinds of reason – political, economic, financial, business.” — Cardinal Turkson, speaking to Edward Pentin

First, are the leaders of the world’s richest entities really willing to make fundamental changes in their way of doing business to promote justice and social charity? Are they really inspired by the mandates of the Gospel and of Catholic social teaching, or only by the latest secular ideas popular among the world’s elites?

Or are most of these commitments merely examples of corporate public relations, with little or no relationship to advancing social justice, as that term has been used and understood by the Church since at least the time of Pius XI? Are these firms merely hoping to use the good name of the Church and of Pope Francis to give credibility to what is nothing more than corporate doublespeak undertaken to save capitalism — and the wealth of the world’s elite at the same time?

Or perhaps this is simply a result of the realization on the part of those who have exploited the world for their benefit up to now that they should temper their actions, or otherwise there simply won’t be a world left for them to exploit anymore?

It is hard to answer these questions, given the vagueness of some of their proposals. The fact that Council members “will be invited to attend biennial conferences on inclusive capitalism held in Rome” does not augur well for very close involvement with the Holy See.

As one critic put it: “The group is yet another front group in what is becoming a globalist bum’s rush to try to convince skeptical world that the same people who created the post 1945model of IMF-led globalization and giga-corporate entities more powerful than governments, destroying traditional agriculture in favor of toxic agribusiness, dismantling living standards in industrialized countries to flee to cheap labor countries like Mexico or China, will now lead the effort to correct all their abuses? We are being naïve if we swallow this.”

It’s important to keep in mind that the richest companies and people in the world are often aligned with goals that are usually understood as politically “on the left.” They realize that achievement of these goals does little or nothing to threaten their profits. For Catholics trying to understand our often confusing political and economic environment, the first, most necessary thing is to stop thinking in terms of right and left, conservative and liberal, if we hope to have any chance of understanding what is really going on in the world today.

It may be, though, that the Vatican is not totally on board with all of this, but feels that any actions, however imperfect, toward a more ethical economy on the part of the financial elite ought to be encouraged. We can maybe discern some of this ambiguity in an interview with Cardinal Turkson by reporter Edward Pentin on February 10 of this year.

Cardinal Turkson stated: “And so, therefore, if you ask what our hopes are, we don’t have any prescriptions. We are also following what Benedict XVI taught about the need for dialogue between faith and reason, all kinds of reason — political, economic, financial, business. So it’s in the line of duty actually, that we do all of this, and our hope is that we’ve been able to find some comprehension and understanding between faith and reason and help everybody realize what they’re applying themselves to.”

The members of the Coalition and Council do not seem likely to act like Zacchaeus in the Gospels, who committed to give away half of his possessions and recompense anyone he had defrauded, fourfold.

Nor do they seem inclined to make an attempt to implement Pius XI’s call, in Quadragesimo Anno, for “Reconstructing the Social Order and Perfecting It Conformably to the Precepts of the Gospel.” Whether they have an agenda beyond convincing the world that capitalists have had a change of heart or not is not clear. Their future actions will reveal this better than their present words.

The Church herself has neither condemned capitalism nor endorsed it, as such. When Pius XI characterized capitalism in Quadragesimo Anno, no.100, as “that economic system in which were provided by different people the capital and labor jointly needed for production” he noted that “the system as such is not to be condemned.”

But he as well as both his predecessors and successors set forth very specific and stringent guidelines for how capitalism would have to work in order to be acceptable. Needless to say, it has rarely lived up to those standards, which go far beyond making sure that food is “great tasting.”

As well as insisting on both social justice and social charity, the Church has told us over and over again that man’s true good does not consist in a preoccupation with mere material goods. While it may be impossible to plumb the motives of those who established the Council for Inclusive Capitalism, the Church’s mission is the same: the reign of Jesus Christ over both individuals and nations, which includes the establishment of justice and charity in economic life.

Thomas Storck is the author of four books and numerous articles on Catholic economics. He is a contributing editor to The Distributist Review and a member of the editorial board of The Chesterton Review.

The Full List of “Guardians” of the Council for Inclusive Capitalism

In December of 2020, while the world was still grappling with the Coronavirus and distracted by the tumultuous presidential elections in the United States, the Vatican, in partnership with some of the world’s most powerful business and investment leaders, launched the “Council for Inclusive Capitalism” with the Vatican.

A core group of “global leaders,” known as “Guardians for Inclusive Capitalism,” plan to meet with Pope Francis and Cardinal Peter Turkson, head of the DIcastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, on an annual basis.

These “leaders,” says a press release, “represent more than $10.5 trillion in assets under management, companies with over $2.1 trillion of market capitalization, and 200 million workers in over 163 countries.”

Speaking to the Guardians at their December 8, 2020 launch, Pope Francis said, “An economic system that is fair, trustworthy, and capable of addressing the most profound challenges facing humanity and our planet is urgently needed. You have taken up the challenge by seeking ways to make capitalism become a more inclusive instrument for integral human wellbeing.”

The Guardians:

Ajay Banga, President, Chief Executive Officer, Mastercard

Oliver Bäte, Chairman of the Board of Management, Allianz SE

Marc Benioff, Chief Executive Officer, Founder, Salesforce

Edward Breen, Executive Chairman, Dupont

Sharan Burrow, General Secretary, International Trade Union Confederation

Mark Carney, COP26 Financial Advisor to the Prime Minister, and United Nations Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance

Carmine Di Sibio, Global Chairman, Chief Executive Officer, EY

Brunello Cucinelli, Executive Chairman and Creative Director, Brunello Cucinelli S.p.A.

Roger Ferguson, President, Chief Executive Officer, TIAA

Lady Lynn Forester de Rothschild, Founder, Managing Partner, Inclusive Capital Partners

Kenneth Frazier, Chairman, CEO, Merck & Co., Inc.

Fabrizio Freda, President, CEO, The Estée Lauder Companies

Marcie Frost, Chief Executive Officer, CalPERS

Alex Gorsky, Chairman and CEO, Johnson & Johnson

Angel Gurria, Sec. General, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

Alfred Kelly, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Visa Inc.

William Lauder, Executive Chairman, The Estée Lauder Companies

Bernard Looney, CEO, BP

Fiona Ma, Treasurer, State of California

Hiro Mizuno, Member of the Board, Principles for Responsible Investment

Brian Moynihan, Chairman of the Board, CEO, Bank of America

Deanna Mulligan, President and CEO, Guardian Life Insurance Company of America

Ronald P. O’Hanley, President and Chief Executive Officer, State Street Corporation

Rajiv Shah, President, The Rockefeller Foundation

Tidjane Thiam, Board Member, Kering Group

Darren Walker, President, Ford Foundation

Mark Weinberger, Former Chair and CEO of EY, and Board member of J&J, MetLife and Saudi Aramco

Facebook Comments