Christ is the arrival of the Kingdom of God in person. He is the new Temple and the new Altar, the new Priest and the final Sacrifice…

By David Fagerberg, Ph.D.

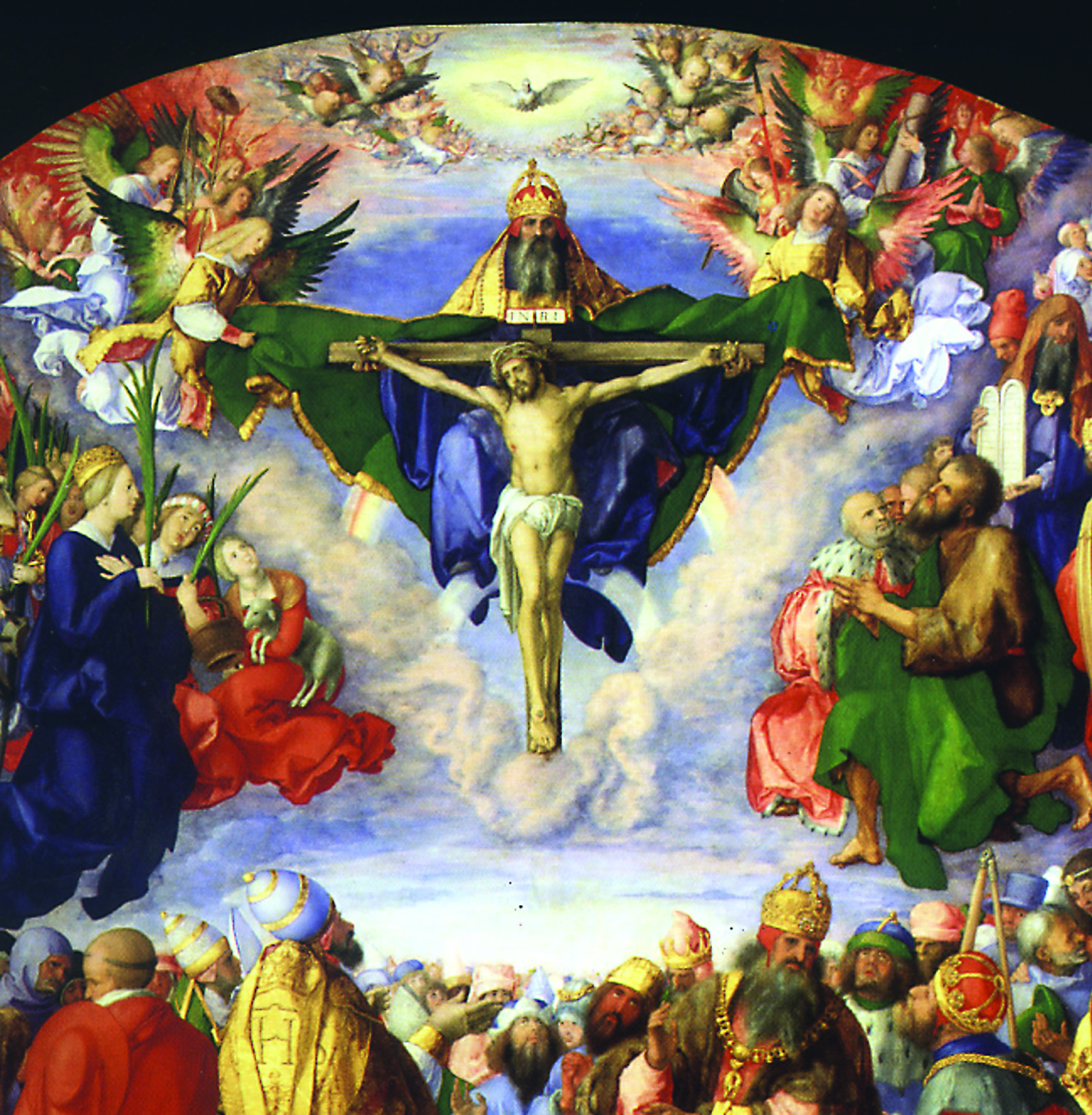

Adoration of the Trinity (Landauer Altar) by Albrecht Dürer, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Austria

St. John Chrysostom

“Strange! What Friendship! For He tells us His secrets; the mysteries of His will… This He desired, this He travailed for, as one might say, that He might be able to reveal to us the mystery. What mystery? That He would have man seated up on high”

There is a line of demarcation, supernatural and mystical in nature, that separates the holy activities of the Church from any secular analogues. This sacred circumference reminds us that the mystical body of Christ is not the same as a religious Jesus club, that the priestly instrument Christ uses is not the same as a counseling therapist, and that sacraments communicating divine life are not the same as teaching aids for a philosophy of life. I think we could call this perimeter sacramental in the sense that God gives a human activity a power beyond what it could possess in itself. Water is poured, bread is broken, oil is applied; at the same time, regeneration occurs, a substance is converted, and a sick person is united to the passion of Christ. It is a human activity, but a divine work.

This may be equally applied to the whole liturgy. Liturgy is the work of God and the activity of men. Liturgy is not a human product, even if it is a human activity. All things must pass through the hypostatic union before they are of any use in liturgy. All religions have a temple and altar, a priesthood and sacrifice, sacred books and sacred art, but in Christian liturgy this religious paraphernalia has been taken up by Christ to be wielded by his hand, and not ours. Liturgy is different from religious ritual because religion’s purpose has been drastically modified.

It has the goal of attaining contact with God, but Christ is the arrival of the Kingdom of God in person. He is the new temple and new altar, the new priest and the final sacrifice, the word of life and the icon of the Father.

The ancient world knew a plethora of cultic religions, says Alexander Schmemann, but the Christian cult is leitourgia, which transcends the categories of cult as such. Christian liturgy is not one of the cults of Adam, it is the cult of the New Adam perpetuated in his body, the Church. Liturgy is not the religion of Christians, liturgy is the religion of Christ perpetuated in Christians. Christ is unique (the hypostatic union of divine and human natures), the Church is unique (the mystical body of Christ), so the liturgy is a unique activity (it is the Church in motion).

The origin and terminus of liturgy is the Trinity.

So said Pius XII: “The sacred liturgy is the public worship which our Redeemer as Head of the Church renders to the Father, as well as the worship which the community of the faithful renders to its Founder, and through Him to the heavenly Father” (Mediator Dei, 20).

So said Virgil Michel, who transplanted the liturgical movement from Europe to the United States: “The liturgy, reaching from God to man, and connecting man to the fullness of the Godhead, is the action of the Trinity in the Church. The Church in her liturgy partakes of the life of the divine society of the three persons in God” (Liturgy of the Church).

This would seem to indicate that the liturgy originates in a place where scholars forget to look.

Liturgy’s origin is not religious purity rituals, the human need for fellowship, Israel’s temple, or ancient history. It is the Trinity.

We join a liturgy already in progress, begun for twin purposes already decided in the mind of God, namely, his glory and our salvation.

The tradition has named the twin purposes of liturgy as the glorification of God and the sanctification of man. This is the opus Dei, the work God is doing behind and under and alongside our liturgical activities.

Whatever we do must be connected to that mystery.

That mystery has been in the mind of God from before time, says Paul in Ephesians 1, Ephesians 3, and Colossians 1. It is a purpose God set forth in Christ as a plan for the fullness of time; it is a mystery not made known fully until it was discovered to the apostles; and now the plan for all ages can be celebrated at a particular hour.

What is that plan? John Chrysostom sums it up in his homilies on Ephesians. “Strange! What Friendship! For He tells us His secrets; the mysteries of His will… This He desired, this He travailed for, as one might say, that He might be able to reveal to us the mystery. What mystery? That He would have man seated up on high.”

That mystery is Jesus, a man seated up on high. That mystery envelops us, for Jesus carries us with him to the throne of his Father in every liturgy. Christ seems to have a two-stage career. He who was invisible was made visible in Incarnation; he who was visible as our Redeemer has now passed into the sacraments (St. Leo the Great).

The liturgist stands beside Christ, before the Father, in the Holy Spirit. That is the privileged place given to all liturgists who are created in the baptismal font, and there is no other GPS location like it. For the Christian, the altar is the tree of life for Adam and Eve, the ladder for Jacob, the burning bush for Moses, the mercy seat of the ark of the covenant, the holy of holies in Solomon’s temple, the still, small voice for Elijah and then his fiery chariot, the Jordan for John the Forerunner, the cross and empty tomb for Christ. When we stand before the altar we are standing before all these places. The mystery that unfolded across historical time now intends to invade our souls, if we will let it.

Whenever we think of “liturgical movement,” we should think of moving closer to that mystery.

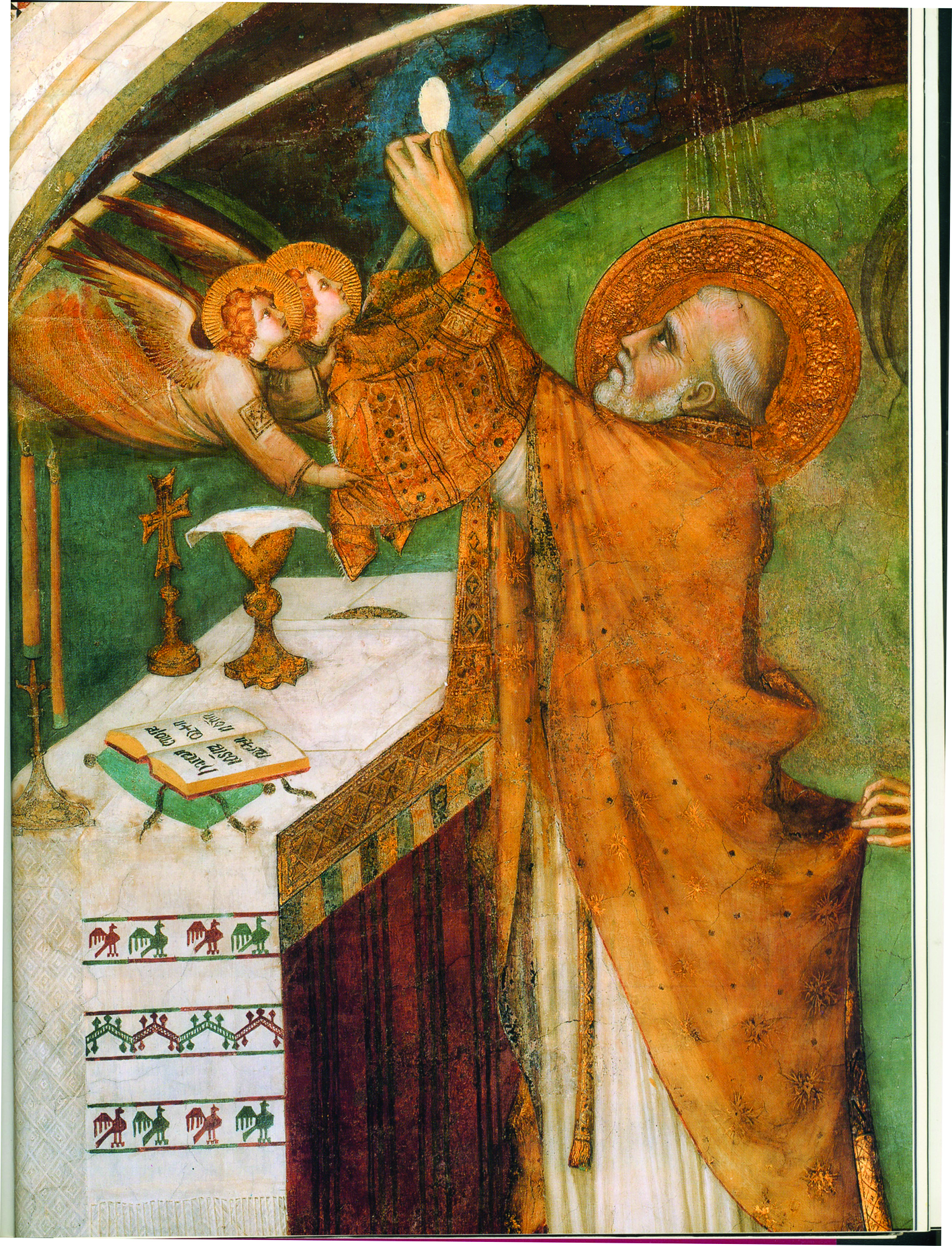

Miraculous Mass, Cappella di San Martino, Lower Church, Assisi, Italy

The liturgist stands beside Christ, before the Father, in the Holy Spirit. That is the privileged place given to all liturgists who are created in the baptismal font, and there is no other GPS location like it

Somehow, I had been given a false impression that the objective was to “move” the liturgy (like the contest of moving a football up and down the field), instead of moving ourselves nearer the liturgy. But that is how participants in the movement originally described it. “The liturgical movement, as the words indicate, is a movement – a movement towards the liturgy;” and “We speak of a liturgical movement because for centuries we have been too far removed from this divine furnace in all its penetrating sacred fire. We have always felt some of its heat, but not enough to get warm” (The Liturgical Movement, ed. Virgil Michel, the former quote by an anonymous author and the latter by Martin Hellriegel).

We may need to connect liturgy to life in order for any of this to make any sense. The public, ceremonial cult is like the part of the liturgical iceberg that we can see, but to what is it connected? What is underneath? The liturgy celebrated and the liturgy lived must be connected. So must be cult and cosmos, sacred and profane, Church and world, the sacramental Christ and our spiritual conversion, the eighth day and our ascetical discipline. The visit to heaven dispels the enchantment of worldliness, his descent opens our ascent, his kenosis achieves our prokope (elevation).

I saw a cloud of incense hovering near the ceiling at the end of Mass one day. The coal had burned out, the grain of incense was gone, both having fulfilled their purposes. But the cloud remained. So it should be with us.

We shall burn out one day. All that matters is the cloud of glory that remains in praise of God. The glory of God is all that matters. Liturgy gives us training and practice for this beatitude.

David W. Fagerberg is Professor of Liturgical Theology at the University of Notre Dame. He has an M.A. from St. John’s University, Collegeville; an S.T.M. from Yale Divinity School; and a Ph.D. from Yale University. Books include Theologia Prima (2003), On Liturgical Asceticism (2013), Consecrating the World (2016), Liturgical Mysticism (2019) and Liturgical Dogmatics (2021).

David W. Fagerberg is Professor of Liturgical Theology at the University of Notre Dame. He has an M.A. from St. John’s University, Collegeville; an S.T.M. from Yale Divinity School; and a Ph.D. from Yale University. Books include Theologia Prima (2003), On Liturgical Asceticism (2013), Consecrating the World (2016), Liturgical Mysticism (2019) and Liturgical Dogmatics (2021).

Facebook Comments