Cyprian’s Perfect Blend of Holiness and Worldly Wisdom Challenged Christians in His Time — and Still Does Today

Cyprian’s Perfect Blend of Holiness and Worldly Wisdom Challenged Christians in His Time — and Still Does Today

By John Byron Kuhner

Last month I wrote about the Latin word pestis, which is usually translated plague, but really should be thought of in a broad sense: not just bubonic plague but any sudden-onset, highly contagious, potentially fatal disease. Coronavirus certainly would count. This month I’d like to take a look at the one Church Father who has a plague named after him: St. Cyprian (200?-258), Carthage’s formidable bishop.

We don’t know a great deal about the 3rd century, in general — we have very few good historical documents from the era — but historians generally agree that between 249 and 262, the Mediterranean basin was ravaged by a terrible unknown disease, called today The Plague of Cyprian. Based on Cyprian’s description, which mentions intense vomiting, fevers, and bloodied eyes, Kyle Harper, a University of Oklahoma Classics professor who studies plague events, has suggested the plague was a hemorrhagic fever like Ebola. No one knows for sure. Scholars have estimated that between 1 and 20 percent of the population of the Roman Empire died; even the low estimate means hundreds of thousands of dead, as the Roman Empire probably had a population of around 50 million at the time. By comparison, we’ve had COVID-19 around for only a few months, and the Mediterranean basin has seen fewer than 10,000 deaths; imagine what has happened recently going on for more than a decade.

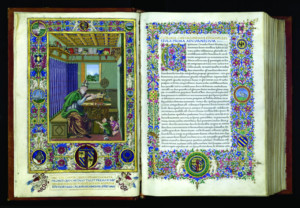

St. Cyprian, in an illuminated manuscript from the Library of Federico da Montefeltro, now acquired by the Apostolic Library in Rome.

There are multiple literary sources mentioning the disease, but the most important come from the pen of Cyprian. Cyprian isn’t well known today. He generally isn’t read in any schools or universities; the only time I encountered even his name was in the classes of the legendary Vatican Latinist Fr. Reginald Foster. Reginaldus would read with students every Latin author he could get his hands on. His was a wonderful way to approach the Church tradition: to become familiar with other fellow Christians of every era simply by reading them. It gave an appreciation for the Church, made up of so many, enduring so much, for so long.

The most important document about the plague is a sermon of Cyprian’s entitled De Mortalitate, “On Mortality.” He frequently uses the term mortalitas as a synonym for “the plague,” or “the disease.” In certain ways this anticipates Albert Camus’s The Plague, where the possibility of sudden death is described as really the normal human condition; most people simply live in denial of it.

Cyprian talks about how some Christians want to be “above” the disease, as if their faith will grant them an exemption from the encumbrances of the flesh:

At enim quosdam movet quod aequaliter cum gentilibus nostros morbi istius valetudo corripiat; quasi ad hoc crediderit Christianus, ut, immunis a contactu malorum, mundo et saeculo feliciter perfruatur… Quoadusque istic in mundo sumus, cum genere humano carnis aequalitate coniungimur.

The Triumph of Death, a 15th century fresco held in Palermo, Museo Nazionale

Translated: “The fact that the strength of this disease overpowers our people just as it does the Gentiles disturbs some people, asif Christians believed only to enjoy the world all the more, safe from the touch of evils…. But as long as we are there, in the world, we are joined with the human race in the equality of the flesh.” (7)

The only way to really understand the theology of these Church Fathers, I’m afraid, is to read their Latin. Look at that unusual phrase, “as long as we are there, in the world.” There is a (generally excellent) translation of this sermon on the EWTN website, and the translator translates istic in mundo as “here in the world.” But that would be hic in mundo or hoc in mundo; Cyprian says istic, “there.” The idea is that the Church, the assembled faithful, were not in the world anymore; they had left the world. When Mass ended, they would go back to the world, as messengers trying to save it. As Fr. Richard Rohr puts it, the modern, secular idea is that you are in the world, and go to church; the old idea is that you are in the Church, and go to the world. People reading in English will miss these old notions because translators often cut them right out.

And since we are here in the world with a mission, Cyprian looks at the plague as an opportunity for transforming one’s life, and breaking from one’s old ways.

Pestis ista et lues, quae horribilis et feralis videtur, explorat iustitiam singulorum, et mentes humani generis examinat, an infirmis serviant sani, an propinqui cognatos pie diligant, an misereantur servorum languentium domini, an deprecantes aegros non deserant medici.

“That plague and disease, which seems horrible and bestial, puts each man’s righteousness on trial, and examines the minds of the human race, to find out if the healthy will serve the sick; if relatives will dutifully love their family members; if masters will have mercy on their languishing slaves; if doctors will not desert their pleading patients.” (16)

We cannot turn our backs on doing good things for each other. Cyprian acknowledges that martyrdom may come from this course of action, and that such a thing is more to be celebrated than feared.

But he also firmly taught that one must never seek martyrdom. In fact, during a period of persecution, Cyprian himself went into hiding to continue running the diocese of Carthage. The point was to continue the life of faith and works, and have death find you doing those things.

If you read enough Cyprian, you’ll find a theme running through his work: he believes in toughness, in integrity under duress, in discipline, and in duty. It looks a bit like Roman ideas of manliness, and in fact it does have some of the sexist flavor found in Roman sources.

Among the things Cyprian declares might weaken a person’s faith in time of plague, he mentions “softness of sex” (mollitie sexus). But Cyprian’s ideal really isn’t the same as Roman manliness, and it’s not a sexist idea, either: courage, for Cyprian, wasn’t killing others on the field of battle, but tending to the sick in their beds, the kind of thing that everyone can do. In this sermon he also mentions turning away from greed and helping the poor.

As Christians look for models in these very unusual times, St. Cyprian might just offer the perfect blend of holiness and worldliness: knowledge that our lives are not ended at death, but awareness that we are all equally subject to the sufferings of the flesh; resolution in the face of death, but without foolhardiness, and not for its own sake. “Be cunning as serpents, but innocent as doves.” For St. Cyprian, what really counts before the Judge who will ultimately judge us is how we have treated the sick, the suffering, and the poor.

Facebook Comments