By Aurelio Porfiri

Nativity by Domenico Ghirlandaio, Vatican Museums

Introitus, Puer natus est (“A child is born”), medieval Gradual from the Poor Clare Monastery in Bamberg, Germany

When the time of the Christmas season approaches, we are often taken by the consumerist frenzy that pushes us to buy a certain food or certain decorations to make the celebration more heartfelt. Christmas has now become mainly a celebration of being with family, losing much of its true meaning – that of welcoming Emmanuel, “God with us.”

If you think about it, Christmas is apparently a simpler feast than Easter. At Christmas we celebrate the birth of a child; what could be more natural and familiar? At Easter we are faced with the unheard-of claim of a man who rises from the dead; it is a little more difficult to digest. And yet, looking deeper, even Christmas asks us for an important act of faith, because He who is born is not a child like any other, but the Savior.

We all know that music is such a fundamental part of the Christmas season. How many Christmas songs are there, residing in the memories of all of us? Yet I believe that even in this, we have lost a lot. For example, the popular Adeste Fideles is a song that is often sung in, at best, questionable translations (e.g., “O Come, All Ye Faithful”), and which, in my opinion, is much more beautiful and significant in the nobility of the Latin version.

But let us also think of Gregorian chant, ousted from the Christmas celebrations in the name of the Second Vatican Council, which in reality had called it the proper song of the Roman liturgy. Isn’t that strange?

Other Christmas songs come to mind, like Puer natus in Bethlehem, austere and noble, with the beautiful refrain with an ascending melody: “With joy in our hearts, let us adore the born Christ, with a new song.” This beautiful song and the austerity it transmits tells us that Christian joy is not the superficial joy that shines through in so many songs used in the liturgy today. It is, rather, like a fire that smolders.

The well-known Italian writer Camillo Langone, reviewing one of my volumes on liturgical chant in 2013, said: “St. Cecilia, pray for Aurelio Porfiri who, being a Roman musician faithful to the Holy Roman Church, lives and works in Macau. In Il canto dei secoli (Marcianum Press) he obviously writes about sacred music but presents valid criteria for judging the catholicity of any other artistic language, including painting and architecture. The Church, says Porfiri, must be ’self-contained’ and not a ‘receptacle’: for example, the organ is the sound of the ‘self-contained Church’ (being intrinsic to the sacred); the guitar, an instrument of a ‘receptacle-Church’ (being intrinsic to profane music and thrown into the liturgy from the outside).

“But my favorite page is number 80, where objectivity also becomes subjectivity, even taste. Porfiri is against a liturgical music that always gives a ‘representation of life as joy.’ For me also, joyful music in church makes me nervous. St. Cecilia, pray for us little-loved lovers of austere, severe, even sad liturgical music, we who in church seek the reason for pain, because the reasons for pleasure are found everywhere.” They seem very beautiful words to me.

But returning to Christmas, let us think of the Introit of the Mass of the day, Puer natus est nobis, with that opening on the fifth interval that almost seems like a trumpet blast announcing an event that will change the history of humanity.

The musicologist and expert in Gregorian chant, Fulvio Rampi, speaking of this Introit, says: “And finally, in the Mass of the day, the Son generated by the Father, new Light that shines on us, takes shape in the ‘Puer natus.’ It is always Isaiah 9 that offers the text to this Introit, where the prophet announces the birth of a ‘child’: this is a correct translation of the term ‘puer,’ which immediately resounds in all its strength, but which requires that it be enriched with meaning. The messianic imprint of that ‘puer’ in fact invites us to expand our understanding towards a far broader perspective than the atmosphere of the crib. The same ‘child’ is immediately understood as a ‘servant,’ called to carry out the saving plan of the Father and on whose shoulders – as the second sentence of the same Introit warns – all power has been placed.”

Unfortunately, today we do not understand the exegetical importance that Gregorian chant has, as it is a contemplative meditation on liturgical texts, not simply music arranged using a given text.

Catholic composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525-1594).

But in addition to Gregorian chant, we cannot forget the musical treasures of polyphony for Christmas time. I am thinking, for example, of the Hodie Christus natus est by the greatest of all Catholic composers, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525-1594), of which there are two versions, one for double choir (from 1575) and one for four voices, always with the beautiful acclamation “Noè, noè” which derives from the French “Noel.” Examples could really be made by the thousands, all treasures of sacred music (to be preserved, according to Vatican II) which instead have been thrown away without a backward glance.

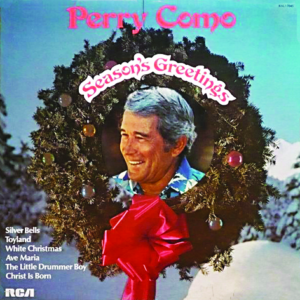

I would like to mention one more piece very dear to me: Christus est by Cardinal Domenico Bartolucci (1917-2013), who was master of the Sistine Chapel for almost 40 years and who was also my teacher. I have often sung this beautiful piece under his direction, at the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music. It is a piece that immediately introduces you into the atmosphere of Christmas. Then, it is also probably his piece best known on American soil thanks to… commercial music! Yes, commercial music. From what he told us, it seems that an American producer listened to this piece and decided that it could work commercially if it was turned into a popular Christmas song. He then asked Ray Charles to write a text for this Christmas motet in English, and “Christ is Born” was born, made famous by Perry Como and also the Carpenters. Maestro Bartolucci jokingly told us that he had earned more with this Christmas song than with all his other compositions, of which there were many.

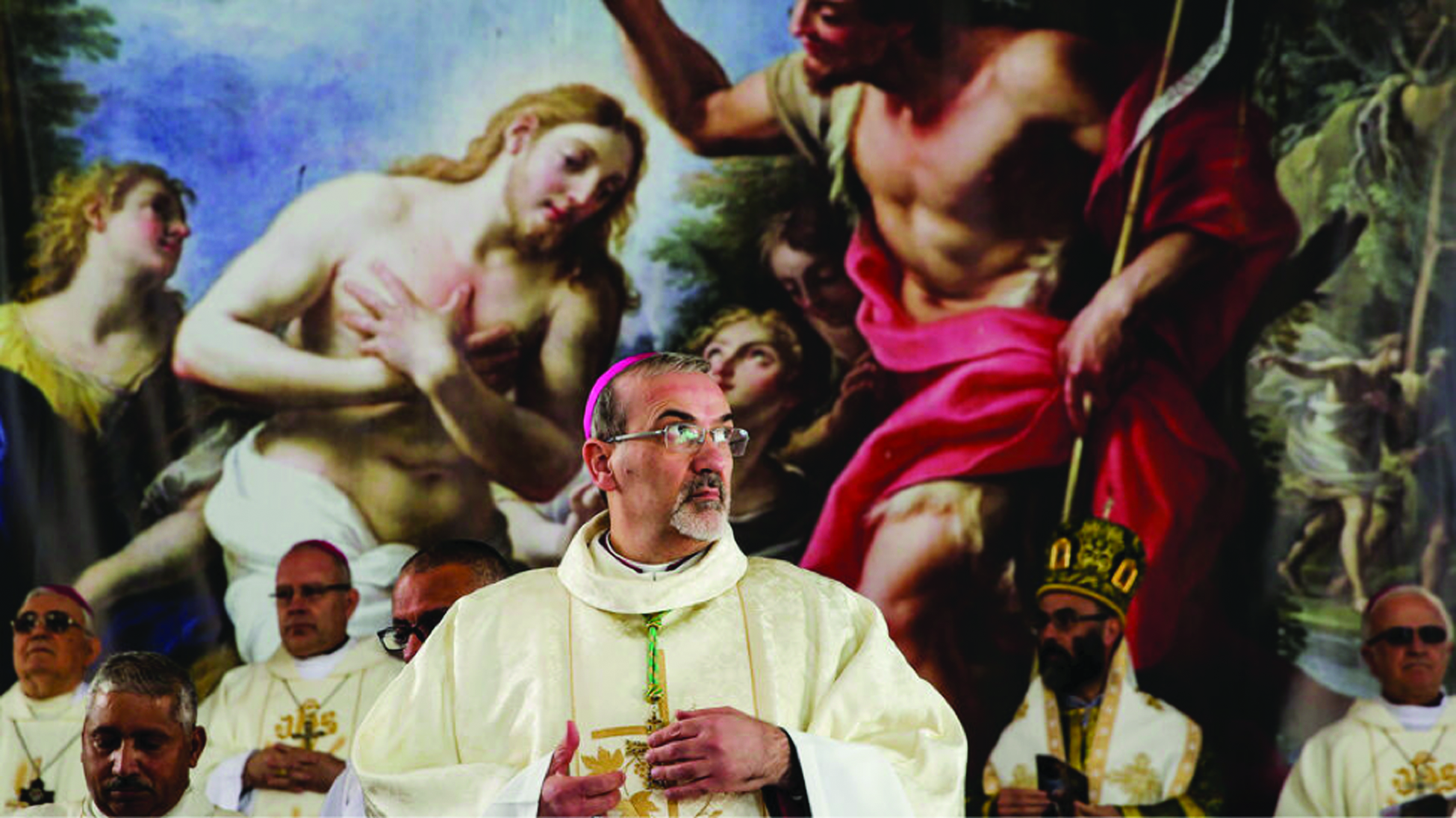

Cardinal Domenico Bartolucci (1917-2013)

Perry Como’s Christmas album containing his piece Christus est

Why does sacred music – even for Christmas – seem so impoverished today? Obviously, it suffers from the general crisis of the liturgy, and of Christianity. A crisis that is mentioned within the Church, but without too much attention paid to it. A crisis that is believed to be resolved not by converting the world, but by converting to the world, allowing oneself to be crushed by its mortal embrace. A crisis that attempts to hide behind the blaming of “traditionalists,” these dangerous Catholics who must be absolutely canceled because otherwise, someone might realize that in the liturgy that is served up to us something has gone really wrong… that much of what is sung in church is actually unworthy and offensive to God, and is completely misleading and detrimental to the faithful. In a time when the Church is apologizing for everything, when will it apologize for the liturgical and musical abuses that have alienated so many faithful and attracted others for the wrong reasons?

This has been one of the greatest devastations of the last few decades. May God give our children and grandchildren a Christmas more liturgically and musically dignified than most of us have had!

Facebook Comments