The evil of lighting fires of destruction with the tongue — and the keyboard

By Prof. Anthony Esolen

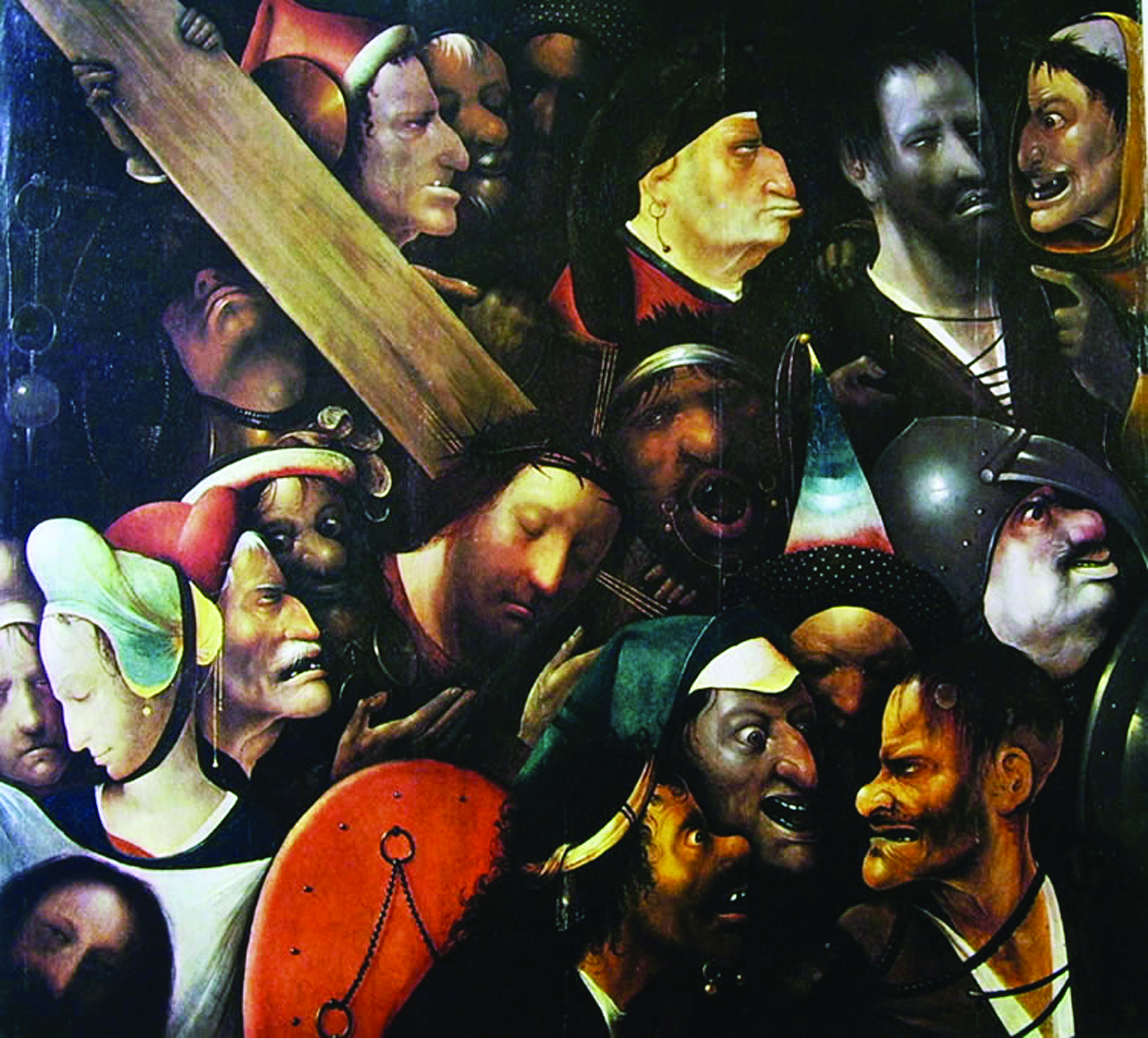

Highlight from the troubling Christ Carrying the Cross, attributed to a follower of Hieronymus Bosch, Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent, Belgium

“The tongue is a fire,” says Saint James. “The tongue is an unrighteous world among our members, staining the whole body, setting on fire the cycle of nature, and set on fire by hell” (3:6). The poet Spenser must have been reading those verses when he asked himself what kind of creature would be most inimical to justice and courtesy, making it impossible for people to live together. He came up with the Blatant Beast, coining the adjective from Latin blatire, to babble. Set on by the hags Envy and Detraction, the Blatant Beast is a monster of a thousand tongues of sundry kinds and sundry quality:

Some were of dogs, that barked day and night,

And some of cats, that wrawling still did cry:

And some of bears, that groaned continually,

And some of tigers, that did seem to grin

And snarl at all, that ever passed by;

But most of them were tongues of mortal men

That spake reproachfully, not caring where nor when.

The Beast spits out his venom against man and woman, low and high, priest and lay, nor are good people safe from him. Detraction makes sure of that:

For whatsoever good by any said

Or done she heard, she would straightway invent

How to deprave, or slanderously upbraid,

Or to misconstrue of a man’s intent,

And turn to ill the thing that well was meant.

Of course, when James wrote his epistle, the worst that the ordinary ill-bridled tongue could do was to make miserable the lives of his neighbors. When Spenser wrote, the fire could spread to a cache of gunpowder, for the printing press had been invented, and lies could go round the literate of a country before the truth, meek and hesitant, had put his shoes on. And now, when lies can circle the earth with near instantaneity and reach billions, it is as if the world of men were soaked in gasoline and everyone with a keyboard and a taste for sowing discord could toss torches left and right, day after day: vandals against the peace.

Only now, when I am growing full of years, and I have seen the harm that a vicious lie can do, have I come to understand the cry of the embittered psalmist: “They make their tongue sharp as a serpent’s, and under their lips is the poison of vipers” (Ps. 140:3). I had thought of persecution, too, only in terms of physical violence, or of pillage and destruction, but now I feel the power of the Lord’s words as he places himself and his followers on the side of the slandered: “Blessed are you when men revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account” (Matthew 5:12). For the commandment forbids us more than speaking what happens not to be the case: “You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor” (Exodus 20:16). We break the commandment whenever we set ourselves in enmity against anyone by the falseness of the tongue, and that includes, in Catholic moral theology, the sins of rash judgment, exaggeration of evils, suppression of considerations that weigh in the victim’s favor, and detraction, in some ways the worst of all. For the victim of detraction cannot defend himself by denying the charge.

Notice that Saint James does not condemn the tongue simply because people tell lies. We can be false in more ways than one. Man has tamed every creature, says the apostle, but he has not learned to tame the tongue, “a restless evil, full of deadly poison,” for “from the same mouth come blessing and cursing” (3:8, 10). Echoing the words of the Lord, James asks whether we can expect fresh water – the Greek idiom is sweet water – from the same well that bubbles up with what is brackish and foul (11).

But what inclines us to speak ill? What tempts us to break charity with others, charity which “does not rejoice at wrong, but rejoices in the right” (1 Cor. 13:6), so that we are happy to hear something bad about a political opponent, or about someone from the wrong party or the wrong sex or the wrong race, but are disappointed when we learn that the person has not been so bad after all? James lays the blame on “bitter jealousy and selfish ambition” (James 3:14). Latin ambitio has to do with ceaseless and unseemly political action: the homo ambitiosus is the man making the rounds, canvassing for votes. But the Greek eritheia here has to do with quarrelsomeness, rivalry, strife. If it is hard to imagine political life without ambition, quarrelsomeness, rivalry, and strife, then all the more should we strive to cordon off the most important areas of our lives from the evil influence. Yet how can we do that, if we spend all day soaking ourselves in strife, wagging the tongue and bending the ear, lighting fires and then roaring with delight when one reputation after another comes crashing down?

Again, I am not talking only about lies. A man may tell the facts about a sinner and damn himself for doing so, “for where jealousy and selfish ambition exist, there will be disorder and every vile practice” (3:16). We must always remember that our Lord, the merciful advocate on our part, will put the best construction on our feeble charity that it can bear, while casting our more obvious enmity in a merciful light. “Father,” said he of the mob who slandered him and nailed him to the cross, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34). James surely has the manner and the words of Jesus in mind. The wildfire of the tongue is beholden to an evil wisdom, “earthly, unspiritual, devilish” (James 3:15). But “the wisdom from above is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, open to reason, full of mercy and good fruits, without uncertainty or insincerity” (17).

“Blessed are the peacemakers,” says Jesus, a verse often cited by Christians who doubt that any war can ever be justified (Matthew 5:9). I am not a pacifist in that sense. It is easy to say, “I oppose this war,” but not so easy to refrain from the everyday wars of human life: vituperation, backbiting, harmful gossip, and obstinacy. Here too the tongue is like fire. Once you have said a thing, it is hard to retract it and impossible to unsay it. Indeed, you may grow perverse; you insist upon it. You burn one field, and rather than admit your folly and help to put out the fire, you fling torches to burn down nine more fields as well. You are at war. But, says the apostle, “the harvest of righteousness is sown in peace by those who make peace” (James 3:18).

Facebook Comments