It’s hard, even for a pope, to change Vatican ways.

By John Byron Kuhner

October 26, 2005 in the Vatican Grottoes, Polish Msgr. Mieczyslaw Mokrzycki, who had been one of Pope John Paul II’s personal secretaries, in prayer at the latter’s tomb.

Things don’t change all that much in St. Peter’s Basilica. Perhaps you have visited the bronze statue of St. Peter, the one whose foot has been rubbed off by pilgrims’ kisses, and want to see it again; well, you’ll find it just where it’s always been, on the right side, just before the dome. That Bernini statue of Death holding an hourglass is just past the transept on the left; the Holy Door is still the one all the way to the right in the front of the basilica. (Note: The statue of Death is part of the Pope Alexander VI tomb; Alexander, born Rodrigo di Borgia in Spain in 1431, was Pope from 1492 to 1503, and fathered several children, including the famous Lucrezia Borgia.) It’s true the Pietà wasn’t always in the first chapel on the right, but it’s been there since 1749, so your guidebook probably has its location correct. But you need a somewhat up-to-date guide if you’re looking for the remains of the beatified Innocent XI (1611-1689, Pope 1676-1689). His body was at the altar of the second chapel on the right, but it was moved in 2011, which in Vatican terms counts as a recent development. Why was he moved? To install in its place the body of now-St. John Paul II, whose visitors were flooding the Grottoes beneath until the decision to move him into the more crowd-friendly basilica. Innocent XI, it seems, was not quite so popular anymore as to merit the altar next to the Pietà.

The present-day tomb of John Paul, in the second chapel on the right entering St. Peter’s Basilica.

When I visit my friend Fr. Reginald Foster, OCD, in Milwaukee, I like to tell him about the changes in Rome. Foster lived in Rome for the better part of 47 years, serving as Latin secretary to four different Popes, until he reached the retirement age of 70 in 2009 and returned to his hometown of Milwaukee. Most of our conversation is about people he knew, stores he used to go to, and things like that. In fact I didn’t even think to tell him about JPII getting a plum spot in the basilica, and I simply mentioned it offhand to him one day, when talking about something else: “So I went right by the altar of John Paul II…” “Wait!” he interrupted. “John Paul has an altar in the basilica?” “Sure,” I said. “Which one?” “The second one on the right.” “Just after the Pietà?” “Yeah.” “So they moved him up from the Grottoes?”

I was surprised by Foster’s curiosity. He has a well-known hatred for pomp. When I once asked him which Pope was buried in a certain tomb, he replied with a verse of Scripture, in Latin: Sine ut mortuisepeliant mortuos suos: tu autem vade, et annuntia regnum Dei. “Let the dead bury their own dead, but you go and proclaim the kingdom of God.” He was making a point: You’re here in Rome; keep your focus on God; don’t get caught up in the Vatican pomp. Why was he, of all people, now interested in who got buried where?

“What does the inscription on the tomb say?” Foster was almost breathless with anxiety.

“I think it just says ‘IOANNES PAULUS II’ or something like that.”

“With an ‘I’ or a ‘J’?”

“I think with an I, but I’ll have to go and check. Why?”

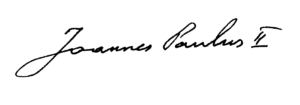

“Well, it’s a long story,” he said, as I settled in. “In 1978, after John Paul II was elected, he had to sign his first document, and he wrote a big long loopy ‘J’ as the first letter. Now we all looked at each other, and sent the thing back. We said, ‘We’re very sorry but there’s no ‘J’ in Latin, Your Holiness. Your name is IOANNES, not JOANNES.’ Well, we get a note back from him saying, ‘Quod scripsi scripsi.’‘What I have written, I have written.’ Basically, ‘Buzz off!’And that was just the start of it! We went back and forth on this for years. Whenever we had the chance, we wrote ‘Ioannes,’ in inscriptions, in letters, and so forth, because that’s good Latin. But in all kinds of places, whenever he noticed, he’d change it to ‘Joannes.’ Fine. And then he dies in 2005, and we do the inscription for his tomb.” Foster flashed his mischievous grin. “So what does it say? ‘IOANNES.’ With an ‘I.’” Foster glows with a look of smug satisfaction. The survivors always get the final say.

“Well, it’s a long story,” he said, as I settled in. “In 1978, after John Paul II was elected, he had to sign his first document, and he wrote a big long loopy ‘J’ as the first letter. Now we all looked at each other, and sent the thing back. We said, ‘We’re very sorry but there’s no ‘J’ in Latin, Your Holiness. Your name is IOANNES, not JOANNES.’ Well, we get a note back from him saying, ‘Quod scripsi scripsi.’‘What I have written, I have written.’ Basically, ‘Buzz off!’And that was just the start of it! We went back and forth on this for years. Whenever we had the chance, we wrote ‘Ioannes,’ in inscriptions, in letters, and so forth, because that’s good Latin. But in all kinds of places, whenever he noticed, he’d change it to ‘Joannes.’ Fine. And then he dies in 2005, and we do the inscription for his tomb.” Foster flashed his mischievous grin. “So what does it say? ‘IOANNES.’ With an ‘I.’” Foster glows with a look of smug satisfaction. The survivors always get the final say.

Foster is really only partially correct about the Latin, by the way — Latin does have a ‘J,’ and in fact the J was invented for setting Latin text.

However, it belongs to that category known as “Late Latin,” the Latin of Medieval and Renaissance Europe.

Initially J was nothing more than an ornamental flourish used when there were two or more I’s in a row.

In 1524, however, Gian Giorgio Trissino decided to use the two different I characters in his printing set to differentiate between two phenomena in Latin that are indeed ancient: the letter I as a vowel (as in the word ierunt, pronounced “ee-ay-roont,” meaning “they went”) and the letter I as a consonant, sounding like Y, as in Iesus, pronounced “yay-zus,” with two syllables not three.

You would not use “J” in ierunt, because I is a vowel there, but you might in Jesus. It’s just a “modern” (if you call 1524 modern) way of recording an ancient Latin phenomenon.

The ancient Romans did not have lower-case letters either, or cursive writing, but Foster did not object when John Paul used both in his signature.

The I/J distinction occurs also in the movie Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, where Indiana Jones has to walk through a booby-trap named the “Path of God.” Since this path was supposedly built during the Crusades in the 12th century, it uses Latin, and Jones has to walk on letters that spell out IEHOVAH (the Latin equivalent of what we now write as Yahweh). And he is given the option of using the letter J, which he must decline, because Latin doesn’t have the letter J. But of course a 12th century booby-trap wouldn’t have the letter J at all, either as a correct or incorrect answer. But that kind of strict logic doesn’t have much place in the movie, which is absurd in many places but ultimately quite entertaining.

Now whenever I walk past the resting place of John Paul II, which is generally thronged with crowds, I find myself smiling — first of all at the man’s popularity even in death, which is a good thing, and second at the little Curial tussle behind the man’s Latin name.

When the body was moved and the inscription re-set, it was left as written, and the “I” remains in place today.

The word “SANCTVS” was added in 2014, after the Pope’s canonization. SANCTVS IOANNES PAVLVS II.

It has a pleasantly classical look, which always looks good in Rome; and it’s a symbol of just how hard it is for a Pope to change entrenched Vatican ways.

Facebook Comments