By Robert Wiesner

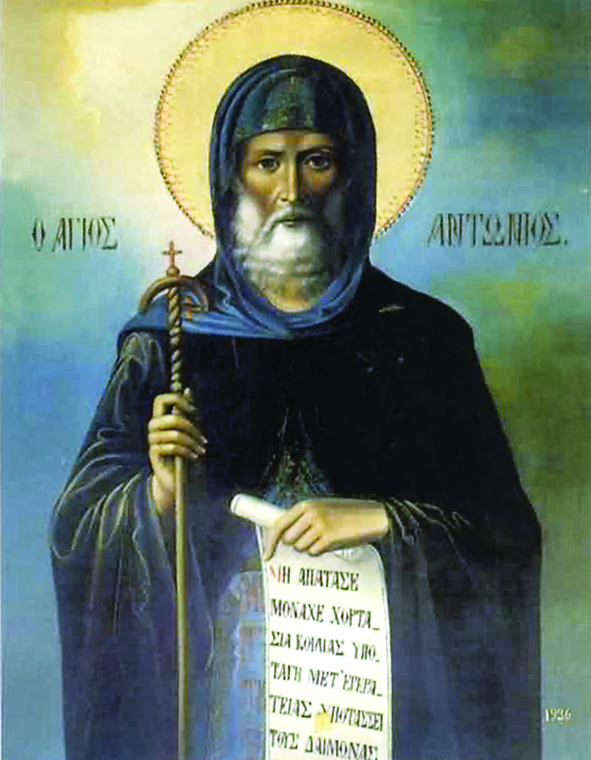

Saint Anthony, father of desert monasticism in Egypt in late 200s

Many these days style themselves as “spiritual” and practice all manner of prayer techniques and forms of inner pacification. Outward calm, tranquility, and lower blood pressure seem to be the benefits of such practices. But the question must be asked, “Does technique actually advance a relationship with God?” While calm and healthy blood pressure are good things in themselves, aiming for them and calling it prayer misses the point entirely. The benefit seems to lie with the self rather than with divine friendship. Prayer techniques with an end-point of tranquility do little to advance one’s contact with God.

Our icon depicts Saint Anthony, father of desert monasticism. His example has nurtured almost two thousand years of asceticism in the wastes of Saharan Egypt. To this very day, monasteries abound in the area. Visitors are greeted with a great deal of silence, broken sometimes by the chanting of the Coptic psaltery. If calm and tranquility might be found anywhere, one could easily place the Egyptian desert near the top of the list. Monks abide in their cells with as little contact with the world as possible, with blood pressure of little concern. And, as is so often seen in the spiritual realm, appearances deceive. Within each monastic cell, something akin to a bar-room brawl is actually taking place. A monk noticing inner tranquility or complacency knows he must immediately change his approach to prayer; he realizes he is in danger of gratifying some aspect of self.

The monk does not seek to gratify the self with tranquility; the desire is to gratify God with the crucifixion of self. The battles with gluttony, greed, and lust effect a constant strife in the life of a monk; they relate the almost universal experience of greeting each day with the resolution to finally make a beginning in monasticism. There will always be some new form of self to master or some hitherto unsuspected tendency to sin needing conquest. The combat with self is a never-ending conflict. The monk faced with gluttony will eat less, the monk tempted to seek fame will flee further into the desert, the temptation to laziness will result in less sleep. The monk cannot afford the slightest indulgence of self; such would be to violate the innermost spirit of monasticism, to betray his vocation.

A Benedictine monk in recent years described his battle in private conversation. He was misunderstood by his fellow monks, thought something of a foolish traditionalist and had a long series of health concerns. He then was diagnosed with throat cancer. His reaction was typical of the man: “Oh, come on, Lord. Is this the best You can do? Come on, give me Your best shot!”

Another ascetic priest was once asked, “What is Christianity all about?” He answered, “Well, it’s about trials, tribulations, suffering, pain, agonies…” His questioner broke in: “I thought it was all about love!” The priest fixed her with a piercing glare: “My dear young woman, that’s precisely what I’m saying!” These two clearly had one of the more striking monastic models in mind, that of Jacob wrestling with the angel of God, resulting in Jacob’s giving of self to the works of God. They understood that coming to grips with divinity involves a great deal of inner turmoil, even if outward tranquility appears to the world.

The spiritual model of inner tranquility and calm can lead to nothing but ultimate disappointment. Coming to grips with God (even for the laity) necessarily involves the Cross and fixing the self upon it; this is rarely a tranquil experience!

Facebook Comments