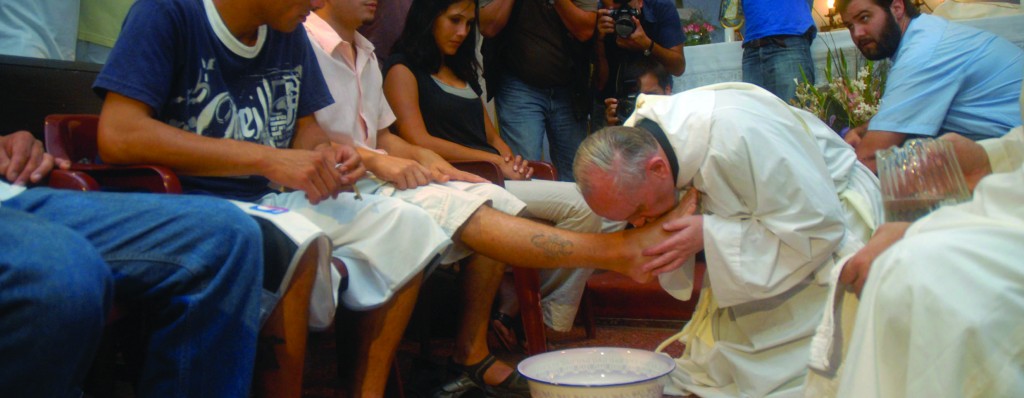

Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio washes and kisses the feet of residents of a shelter for drug users during Holy Thursday Mass in 2008 at a church in a poor neighborhood of Buenos Aires, Argentina (CNS photo/Enrique Garcia Medina, Reuters)

Francis has consistently characterized the law and lawyers as “pharisaical,” but societies — and the Church — cannot function without them

Pope Francis, like Benedict XVI or John XXIII, shows little personal interest in law. But neither Benedict nor John gave what seems to be cover for disregarding laws felt to be inconvenient, and certainly neither of them spoke so often and so negatively about law in general and lawyers in particular, as has Francis during the first three years of his pontificate. Hindsight allows one to see, I suggest, Francis’ impatience with legal concerns even in the first weeks of his papacy.

The rubrics for the Holy Thursday “mandatum rite” had long restricted participation in that rite to males (“viri,” the Latin for “men”). While good arguments for restricting the rite to males and for opening it to women were at hand, liturgical law itself (a function of papal legislative authority) was clear: men only. Over the years many pastors had been excoriated as insensitive when they excluded women from the rite while many others were lauded as liberators from Roman sexism when they violated the rubrics. Enter Francis.

As Pope, Francis could have easily changed the law. Instead he simply disregarded it and washed the feet of women during his first papal celebration of the mandatum. The Pope’s action occasioned, as anyone could have predicted, ridicule for clergy who had observed the rubric and praise for those who had disobeyed it. A rash of ill-formed, often jaded, questions about whether Popes are bound by canon law and, for that matter, why the Church even has law, were suddenly loosed.

Some, concerned not so much with the substance of the rubric as with the effects that disregard for law in high places tends to provoke in other areas of life, excused the event as a beginner’s mistake and suggested that the new Pope had not had time to reform a law he did not like. But such concessions were harder to make when Francis repeated his action at his next two Holy Thursday Masses. Only a few weeks ago. Francis finally did change the mandatum rubric and, to that degree, moot the matter.

The situation of Cardinal Raymond Burke (with whom I have never spoken concerning what follows) suggests that Francis does not understand the complexities entailed in juridic matters and so might not appreciate what is really needed for good lawyering in the highest levels of ecclesiastical life. No one disputes that Burke was one of the finest minds ever placed over the Apostolic Signatura. His academic and linguistic skills, tribunal experience, service as a bishop and archbishop, and canonical speaking and publishing records, made it obvious why Benedict named Burke to head the Church’s highest court in 2008. But while Francis’ removal of Burke from the Signatura in 2014 was quite within the Pope’s prerogatives, the assignment of Burke to duties that could be performed by numerous other prelates suggests, at best, a mistaken belief that the Church enjoys a surfeit of gold-standard legal talent.

Similarly, Francis’ personal invitation of Cardinal Kasper (who argues for the admission of divorced and remarried Catholics to Holy Communion) to participate in the 2015 Synod on the Family, while not inviting Burke (perhaps the most formidable defender of the traditional doctrinal-disciplinary approach at issue, living just a five-minute stroll from Paul VI Hall), implied that the views of the world’s leading canon lawyer were not relevant for the synod.

A third point suggesting Francis’ lack of interest in law — and here we come closest, I suggest, to seeing a certain antipathy toward law itself — is the Pope’s nearly unbroken line of public castigations aimed at law and lawyers. Few examples of Francis mentioning law or lawyers in a homily or other set of public remarks, and not immediately characterizing law as pharisaic and warning lawyers against pharisaism, can be found. Unfortunately, the irony of others, believing that Francis has their backs, now labeling lawyers who defend, say, Christ’s words against divorce as “neo-Pharisees,” even though the historical Pharisees tried to dilute the force of God’s words on marriage, passes unnoticed.

Societies, even religious societies, cannot function without law, and law cannot function without lawyers. One wonders whether the rest of Francis’ papacy will be as difficult for law and lawyers as has been its beginning.

Edward N. Peters has doctoral degrees in canon and common law.

Facebook Comments