February 13, 2013, Wednesday — Pope Benedict’s Unfolding Spiritual Testament as He Prepares to Resign on February 28

“While the Lord continues to raise up examples of radical conversion, like Pavel Florensky, Etty Hillesum and Dorothy Day, he also constantly challenges those who have been raised in the faith to deeper conversion.”—Pope Benedict XVI, at his next-to-last General Audience, this morning in the Paul VI Audience Hall in Vatican City

Benedict Reaches Out

Jews, Protestant evangelicals, and Orthodox Christians will find Pope Benedict’s words this morning of particular interest.

The Pope, in different ways, is reaching out to each group.

And in this outreach, Pope Benedict does not cease to surprise, even to astonish.

After February 28, and his renunciation of the papal throne, the fisherman’s ring which he wears with be broken in half…

Outreach to Orthodox, Jews, and Evangelicals

Pope Benedict continues to give us hints about what he wants those who listen to him and who follow him — both Roman Catholics and all other men and women of good will — to focus on in the days ahead, in our increasingly secularized world.

What Benedict wants all to focus on, Catholic and non-Catholics, believers and unbelievers, is the great “missing element,” the great “not present” in our modern world and society: that is, the hidden God who is the source of all being and goodness, and the true end and answer to all human hopes and longings.

This morning, speaking in English during his General Audience (his next to last General Audience as Pope), Pope Benedict mentioned three people as examples of “radical conversion” who were “raised up by the Lord” as “examples” during the past century: Pavel Florensky, Etty Hillesum and Dorothy Day.

Benedict’s choice of these three, from a certain perspective, could not have been more provocative… because none of the three can be considered a “model” Catholic. None of them were raised in the faith.

(Continued below…)

Special note to readers

Special Note: In the days ahead, I plan to continue to write about the Pope’s resignation and the upcoming conclave. I plan to include some discussion of the prophetic 1917 message of Our Lady Fatima, and how it relates to our present situation in the Church and in the world. Please stay tuned…

Also, the next two issues of Inside the Vatican magazine will be “Special Commemorative Editions” which readers may wish to collect as keepsakes.

The March 2013 issue will focus of Pope Benedict and his pontificate, while looking forward to the Conclave and the choice of a new Pope.

The April 2013 issue will focus on the Conclave and the new Pope chosen at the conclave.

Please consider subscribing to the magazine, so you do not miss these historic issues. (Once the print runs are sold out, we do not expect ever to reprint the issues.)

Finally, for these two special issues, we are actively seeking:

1) supporting sponsors, whose names will be listed (if desired) on a special page in the magazine, and

2) supporting advertisers, who sponsor a page of the magazine as a way of bidding farewell to Pope Benedict as Pope (in the March issue), or as a way of greeting the new Pope after he is elected (in the April issue)

Those who wish to support these two issues of the magazine, or take out an advertisement (for your family, your parish, your organization), please contact us via email at the following address: [email protected].

You may also write directly to me by replying to this newsflash.

—Robert Moynihan, Editor, Inside the Vatican magazine

“Seekers” of God

In fact, the first two people mentioned by Pope Benedict this morning, a brilliant Russian Orthodox philosopher (Pavel Florensky, who was executed by the Soviet regime in the 1930s) and a sensitive Jewish woman writer killed at Auschwitz (Etty Hillesum), were never Catholics at all.

And the third, an American convert to Catholicism (Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement), has always been controversial because she was an active Communist as a young woman, and remained “leftist” in many of her views throughout her life. (I had the chance to meet Dorothy once, in 1976 in New York City.)

But, though not “cradle Catholcis,” the Pope held up these three today as examples because each was a sincere “seeker of God.”

Each was true to a desire, a longing, in their hearts, which set them out, as it sent out St. Augustine, on a search for truth, on a search for that ground of reality which could satisfy their deepest longings.

This is the common thread.

This is what Pope Benedict is stressing today.

He is reaching out to all and saying to all, be true to your deepst longings, to your deepest desire to reach that hidden infinite, that absolute which is also personal, which your soul longs for.

And he is saying that this “remaining true” is an inspiration also for those raised in the faith. He said this morning that the Lord “also constantly challenges those who have been raised in the faith to deeper conversion.”

This is the message of the Pope to Catholics at this time.

The message is: deeper conversion.

The Pope is at pains to make one, central point: that, though values, morals, customs and traditions are critical for mankind, for sinful and imperfect men and women, to come to a more reasonable, more balanced and more “sane” (healthy, healthful, vibrant) human life, the true, mysterious, radical “source” of the fullness of human life and health and sanity and blessedness — that is, the fullness of being saved from frustration and sin and death, the fullness of salvation, of eternal life — is an encounter with, a connection to, a sharing of the very divine life of, God, and of the Son of God, the risen Lord, Jesus of Nazareth.

Those evangelical, Protestant Christians who feel that the Catholic Church, with its vast, global structure of offices, laws and institutions, has lost sight of this central fact, of the need for a personal relationship with Jesus Christ, should feel moved to reconsider their position by these very clear words of this Pope, who is now speaking in the final 15 days of his papacy, so his words in these days may be seen as a sort of spiritual testament.

He is placing God at the center. He is placing Christ at the center. Not himself, not his papacy, not the institutional Church.

Those Jews who have half-suspected, or have even been inwardly certain, that this Pope, a German who was forcibly conscripted into Hitler’s army in 1943, was not a friend to the Jewish people, should be startled by his choice of a young Jewish woman, killed at Auschwitz, as one of the “models” of spirituality he would choose to present at one of his final public audiences.

And those Orthodox who wonder if the Roman pontiff truly respects the Orthodox and their profound spiritual life and tradition, should be moved by the fact that the first name mentioned today by the Pope, in the next-to-last general audience of his pontificate, is the martyred Russian Orthodox theologian, Pavel Florensky.

(Here is a link to a video of the Pope’s words: it may be of interest to you to seen how the Pope appears, in these historic days: https://www.romereports.com/palio/benedict-xvi-pray-for-me-and-the-future-pope-english-9021.html#.URubAY5qeqE)

Here is a brief report, from Rome Reports, on what the Pope said today:

February 13, 2013. (Romereports) “I thank you all for the love and prayers that have accompanied me. Thank you,” said the Pope. “In these difficult days, I’ve felt almost physically, the power of prayer that comes through the love for the Church and your personal prayers. Continue to pray for me, for the Church and the future Pope. The Lord will guide.”

Looking calm and serene, Benedict XVI led his first public appearance, after announcing his resignation. Before a full crowd, he once again said he made the decision with complete liberty. He echoed Monday’s statement by saying that he does not have the strength to carry out the office.

Then he continued with his weekly catechesis, on Ash Wednesday.

He talked about the temptation Jesus experienced when He was in the desert. In today’s modern world, said the Pope, temptation is to push faith aside and seek false solutions.

“While the Lord continues to raise up examples of radical conversion, like Pavel Florensky, Etty Hillesum and Dorothy Day, he also constantly challenges those who have been raised in the faith to deeper conversion.”

During this Lenten season, the Pope invited people to open their minds and hearts, as Christ knocks on their door. A source of true inspiration, he says, is that Jesus himself overcame temptation out in the desert.

The Vatican’s Paul VI Hall was full of pilgrims who greeted the Pope, interrupting him with applause throughout, to show their gratitude for the last eight years.

Background Information on Pavel Florensky, Etty Hillesum and Dorothy Day

Pavel Florensky

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

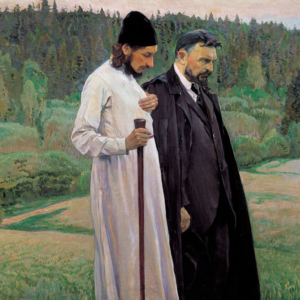

(Philosophers Pavel Florensky and Sergei Bulgakov, a painting by Mikhail Nesterov (1917). Florensky is on the left)

(Philosophers Pavel Florensky and Sergei Bulgakov, a painting by Mikhail Nesterov (1917). Florensky is on the left)

Pavel Alexandrovich Florensky (also P. A. Florenskiĭ, Florenskii, Florenskij, Russian: Па́вел Алекса́ндрович Флоре́нский) (January 21 [O.S. January 9] 1882 – December 1937) was a Russian Orthodox theologian, priest, philosopher, mathematician, physicist, electrical engineer, inventor and Neomartyr.

Early life

Pavel Aleksandrovich Florensky was born on January 21, 1882,[2] into the family of a railroad engineer, (Aleksandr Florensky) in the town of Yevlakh in western Azerbaijan. His father came from a family of Russian Orthodox priests while his mother Olga (Salomia) Saparova (Saparyan, Sapharashvili) was of the Tbilisi Armenian nobility…

After graduating from Tbilisi gymnasium in 1899, Florensky underwent a religious crisis caused by an awareness of the limits and relativity of rational knowledge and decided to construct his own solution on the basis of mathematics. He entered the department of mathematics of Moscow State University and studied under Nikolai Bugaev, and became friends with his son, the future poet and theorist of Russian symbolism, Andrei Bely. He also took courses on ancient philosophy. During this period the young Florensky, who had no religious upbringing, began taking an interest in studies beyond “the limitations of physical knowledge…”

In 1904 he graduated from Moscow State University and declined a teaching position at the University: instead, he proceeded to study theology at the Ecclesiastical Academy in Sergiyev Posad. During his theological studies there, he came into contact with Elder Isidore on a visit to Gethsemane Hermitage, and Isidore was to become his spiritual guide and father.

Together with fellow students Ern, Svenitsky and Brikhnichev he founded a society, the Christian Struggle Union (Союз Христиaнской Борьбы), with the revolutionary aim of rebuilding Russian society according to the principles of Vladimir Solovyov. Subsequently he was arrested for membership in this society in 1906: however, he later lost his interest in the Radical Christianity movement.

Intellectual interests

During his studies at the Ecclesiastical Academy, Florensky’s interests included philosophy, religion, art and folklore. He became a prominent member of the Russian Symbolism movement, together with his friend Andrei Bely and published works in the magazines New Way (Новый Путь) and Libra (Весы). He also started his main philosophical work, The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: an Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters. The complete book was published only in 1924 but most of it was finished at the time of his graduation from the academy in 1908.

According to Princeton University Press: “The book is a series of twelve letters to a ‘brother’ or ‘friend,’ who may be understood symbolically as Christ. Central to Florensky’s work is an exploration of the various meanings of Christian love, which is viewed as a combination of philia (friendship) and agape (universal love). He describes the ancient Christian rites of the adelphopoiesis (brother-making), which joins male friends in chaste bonds of love. In addition, Florensky was one of the first thinkers in the twentieth century to develop the idea of the Divine Sophia, who has become one of the central concerns of feminist theologians.”

After graduating from the academy, he married Anna Giatsintova, the sister of a friend, in August 1910, a move which shocked his friends who were familiar with his aversion to marriage.

He continued to teach philosophy and lived at Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra until 1919. In 1911 he was ordained into the priesthood. In 1914 he wrote his dissertation, About Spiritual Truth. He published works on philosophy, theology, art theory, mathematics and electrodynamics. Between 1911 and 1917 he was the chief editor of the most authoritative Orthodox theological publication of that time, Bogoslovskiy Vestnik. He was also a spiritual teacher of the controversial Russian writer Vasily Rozanov, urging him to reconcile with the Orthodox Church.

Period of Communist rule in Russia

After the October Revolution he formulated his position as: “I have developed my own philosophical and scientific worldview, which, though it contradicts the vulgar interpretation of communism… does not prevent me from honestly working in the service of the state.”

After the Bolsheviks closed the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra (1918) and the Sergievo-Posad Church (1921), where he was the priest, he moved to Moscow to work on the State Plan for Electrification of Russia (ГОЭЛРО) under the recommendation of Leon Trotsky who strongly believed in Florensky’s ability to help the government in the electrification of rural Russia. According to contemporaries, Florensky in his priest’s cassock, working alongside other leaders of a Government department, was a remarkable sight.

In 1924, he published a large monograph on dielectrics, and his The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: an Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters. He worked simultaneously as the Scientific Secretary of the Historical Commission on Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra and published his works on ancient Russian art. He was rumoured to be the main organizer of a secret endeavour to save the relics of St. Sergii Radonezhsky whose destruction had been ordered by the government.

In the second half of the 1920s, he mostly worked on physics and electrodynamics, eventually publishing his paper Imaginary numbers in Geometry («Мнимости в геометрии. Расширение области двухмерных образов геометрии») devoted to the geometrical interpretation of Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. Among other things, he proclaimed that the geometry of imaginary numbers predicted by the theory of relativity for a body moving faster than light is the geometry of the Kingdom of God. For mentioning the Kingdom of God in that work, he was accused of agitation by Soviet authorities.

1928-1937: Exile, imprisonment, death

In 1928, Florensky was exiled to Nizhny Novgorod. After the intercession of Ekaterina Peshkova (wife of Maxim Gorky), Florensky was allowed to return to Moscow.

On the 26 February 1933 he was arrested again, on suspicion of engaging in a conspiracy with Pavel Gidiulianov, a professor of canon law who was a complete stranger to Florenskiy, to overthrow the state and restore with National Socialist assistance a fascist monarchy.

He defended himself vigorously against the imputations until he realized that by showing a willingness to admit them, though false, he would enable several acquaintances to resecure their liberty.

He was sentenced to ten years in the Labor Camps by the infamous Article 58 of Joseph Stalin’s criminal code (clauses ten and eleven: “agitation against the Soviet system” and “publishing agitation materials against the Soviet system”). The published agitation materials were the monograph about the theory of relativity. His manner of continuing to wear priestly gard annoyed his employers. The state offered him numerous opportunities to go into exile in Paris, but he declined them.

He served at the Baikal Amur Mainline camp, until 1934 when he was moved to Solovki, there he conducted research into producing iodine and agar out of the local seaweed. In 1937 he was transferred to Saint Petersburg (then known as Leningrad) where he was sentenced by an extrajudicial NKVD troika to execution.

According to a legend he was sentenced for the refusal to disclose the location of the head of St. Sergii Radonezhsky that the communists wanted to destroy. The Saint’s head was indeed saved and in 1946, the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra was opened again. The relics of St. Sergii became fashionable once more. The Saint’s relics were returned to Lavra by Pavel Golubtsov, later known as archbishop Sergiy.

Official Soviet information stated that Florensky died December 8, 1943 somewhere in Siberia, but a study of the NKVD archives after the dissolution of the Soviet Unionhave shown that information to be false. Florensky was shot immediately after the NKVD troika session in December 1937. Most probably he was executed at the Rzhevsky Artillery Range, near Toksovo, which is located about twenty kilometers northeast of Saint Petersburg and was buried in a secret grave in Koirangakangas near Toksovo together with 30,000 others who were executed by NKVD at the same time.

Etty Hillesum

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, and other websites

“And I also believe, childishly perhaps but stubbornly, that the earth will become more habitable again only through the love that the Jew Paul described to the citizens of Corinth in the thirteenth chapter of his first letter.”—Etty Hillesum, Jewish writer who died at Auschwitz

Esther “Etty” Hillesum (15 January 1914 in Middelburg, Netherlands-30 November 1943 in Auschwitz, Poland) was a young Jewish woman whose letters and diaries, kept between 1941 and 1943, describe life in Amsterdam during the German occupation. They were published posthumously in 1981.

Esther “Etty” Hillesum (15 January 1914 in Middelburg, Netherlands-30 November 1943 in Auschwitz, Poland) was a young Jewish woman whose letters and diaries, kept between 1941 and 1943, describe life in Amsterdam during the German occupation. They were published posthumously in 1981.

During the last two years of her life, she kept a journal of her thoughts, particularly about her relationship with a man named Julius Spier, a mentor, friend, and lover, and her developing relationship with God.

Etty was influenced by Spier and her reading of works such as the poetry of Rilke, the novels of Dostoevsky, and the Gospels. In the face of the very worst of human hatred, Etty was able to find inner peace through a refusal to reciprocate that hate. As such, her work, entitled An Interrupted Life and Letters from Westerbork deserve our attention. Below are some of my favorite quotes from her work. I hope you enjoy.

“Unless every smallest detail in your daily life is in harmony with the high ideals you profess, then those ideals have no meaning.” (p 114)

“I imagine that there are people who pray with their eyes turned heavenward. They seek God outside themselves. And there are those who bow their head and bury it in their hands. I think that these seek God inside.” (p 44)

“Perhaps my purpose in life is to come to grips with myself, properly to grips with myself, with everything that bothers and tortures me and clamors for inner solution and formulation. For these problems are not just mine alone. And if at the end of a long life I am able to give some form to the chaos inside me, I may well have fulfilled my own small purpose.” (p 36)

“What needs eradicating is the evil in man, not man himself.” (p 86)

“God, do not let me dissipate my strength, not the least little bit of strength, on useless hatred against these soldiers. Let me save my strength for better things.” (p 109)

“God, I try to look things straight in the face, even the worst crimes, and to discover the small, naked human being amid the monstrous wreckage caused by man’s senseless deeds.” (p 134)

“I love people so terribly, because in every human being I love something of You [God]. And I seek you everywhere in them and often do find something of You.” (p 198)

“You have placed me before Your ultimate mystery [death], oh God. I am grateful to You for that, I even have the strength to accept it and to know there is no answer. That we must be able to bear Your mysteries.” (p 199)

“‘After this war, two torrents will be unleashed on the world: a torrent of loving-kindness and a torrent of hatred.’ And then I knew: I should take the field against hatred.” (p 208)

“Klaas, all I really wanted to say is this: we have so much work to do on ourselves that we shouldn’t even be thinking of hating our so-called enemies. We are hurtful enough to one another as it is…It is the only thing we can do, Klaas, I see no alternative, each of us must turn inward and destroy in himself all that he thinks he ought to destroy in others. And remember that every atom of hate we add to this world makes it still more inhospitable.” When Klaas makes the objection that this sounds like Christianity, Etty says: “Yes, Christianity, and why ever not?” (pp 211-212)

“And I also believe, childishly perhaps but stubbornly, that the earth will become more habitable again only through the love that the Jew Paul described to the citizens of Corinth in the thirteenth chapter of his first letter.” (p 256)

“I have broken my body like bread and shared it out among men. And why not, they were hungry and had gone without for so long.” (p 230)

Etty Hillesum was only 27 when her journal begins, and we get to see her work out her confusion, anxiety, etc. in the course of her writing. Her relationships with men were passionate, but confused. She was, in short, not perfect.

At the same time, we get to see her come to know God — truly know his truth, and we hear her preach it (as above), and live it. She died in Auschwitz on November 30th, 1943, a year after St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (a Jewish-Catholic), and two years after St. Maximillian Kolbe.

Biography

Louis Hillesum studied classical languages at the University of Amsterdam. In 1902 he completed his bachelor’s degree, followed in 1905 by his master’s (both degrees cum laude). On 10 July 1908 he published his Latin thesis De imperfecti et aoristi usu Thucydidis (On Thucydides’ use of the imperfect and the aorist, also awarded cum laude). Middelburg was his first teaching assignment. In 1914 he began teaching the classics at the Hilversum gymnasium (grammar school), but, due to deafness in one ear and impaired vision, had trouble maintaining order in the large classes at that institution. That is why, in 1916, he moved to a smaller gymnasium in the town of Tiel. In 1918 he became teacher of classics and deputy headmaster inWinschoten. In 1924 he was appointed to similar positions at the gymnasium in Deventer, where he became headmaster on 1 February 1928. He remained there until his dismissal on 29 November 1940, at the request of the occupation government that was imposed by National Socialist Germany….

Childhood

Etty spent her childhood years in Middelburg, Hilversum (1914–16), Tiel (1916–18), Winschoten (1918–24) and Deventer, from July 1924 on, where she entered the fifth form of the Graaf van Burenschool. The family lived at number 51 on the A. J. Duymaer van Twiststraat (at present time number 2). Later (in 1933) they moved to the Geert Grootestraat 9, but by then Etty was no longer living at home. After primary school, Etty attended the gymnasium (grammar school) in Deventer, where her father was deputy headmaster. Unlike her younger brother Jaap, who was an extremely gifted pupil, Etty’s marks were not particularly worthy of note.

At school she also studied Hebrew and for a time attended the meetings of a Zionist young people’s group in Deventer. After completing her school years, she went to Amsterdam to study law. She took lodgings with the Horowitz family, at the Ruysdaelstraat 321, where her brother Mischa had been staying since July 1931. Six months later she moved to the Apollolaan 29, in where her brother Jaap also lived from September 1933 while he was studying medicine. In November, Jaap moved to the Jan Willem Brouwerstraat 22hs; Etty followed one month later.

As from September 1934, Etty’s name once again appeared in the registry at Deventer. On 6 June 1935 she took her bachelor’s exams in Amsterdam. At that time she was living with her brother Jaap at Keizersgracht 612c. In March 1937 she took a room in the house of the accountant Hendrik (Hans) J. Wegerif, at Gabriel Metsustraat 61, an address also officially registered as the residence of her brother Jaap from October 1936 to September 1937. Wegerif, a widower, hired Etty as his housekeeper, but also began an affair with her. It was in this house that she lived until her definitive departure for Westerbork in 1943.

University years

Not much is known about Etty’s university years. She moved in left-wing, anti-fascist student circles and was politically and socially aware without belonging to a political party. Her acquaintances from this period were amazed to learn of her spiritual development during the war years, a period in which she adopted clearly different interests and a different circle of friends, although she did maintain a number of her pre-war contacts. Etty took her master’s exams in Dutch Law (public law in particular) on 23 June and 4 July 1939.

Her academic results were not striking.

In addition, she studied Slavic languages at Amsterdam and Leiden, but the conditions of war prevented her from completing this study with an exam. She did, however, continue to study Russian language and literature until the very end and also gave lessons in these subjects. She taught a course at the Volksuniversiteit and later gave private lessons until her definitive departure for the Westerbork transit camp. The diaries were written largely in her room on the Gabriel Metsustraat, where not only she and Wegerif but also Wegerif’s son, Hans, and a chemistry student by the name of Bernard Meijlink were living.

Julius Spier

It was through Bernard Meijlink that on Monday, 3 February 1941, Etty went to serve as “model” to the psycho-chirologist Julius Spier at the Courbetstraat 27 in Amsterdam. Spier (who is almost always referred to in the diaries as “S.”) was born at Frankfurt am Main in 1887, the sixth of seven children. At the age of 14 he was apprenticed to the Beer Sontheimer trading firm. There he succeeded in working his way up to a managerial position. His original ambition of becoming a singer was foiled by an illness that left him hard of hearing.

Spier enjoyed moving in artistic circles and set up his own publishing house, by the name of “Iris.” In addition, from 1904 on he had a pronounced interest in chirology. Following his 25th jubilee at Beer Sontheimer in 1926, Spier withdrew from business life to dedicate himself to the study of chirology. He underwent instructive analysis withC. G. Jung in Zurich and at Jung’s recommendation opened a practice in 1929 as psycho-chirologist on the Aschaffenburgerstrasse in Berlin. The practice there was extremely successful. Spier also taught courses. In 1934 he divorced his wife, Hedl (Hedwig) Rocco, to whom he had been married since 1917, and left the two children, Ruth and Wolfgang, with her. He had a number of affairs but finally became engaged to his pupil, Hertha Levi, who emigrated to London in 1937 or 1938. Spier also left National Socialist Germany and came to Amsterdam in 1939 as a legal immigrant. After first living with his sister on the Muzenplein, and later in a room on the Scheldestraat, from late 1940 on he rented two rooms from the Nethe family at the Courbetstraat 27. There he also set up practice and taught courses. The students at those courses and their friends invited “models,” whose hands Spier analysed by way of practical example.

Gera Bongers, the sister of Bernard Meijlink’s fiancee, Loes, was one of Spier’s student, and it was through Bernard that Etty was invited to have her hands analysed during a Monday evening class. This fairly chance encounter proved formative for the course of Etty’s life. She was immediately impressed by Spier’s personality and decided to go into therapy with him. On 8 March 1941 she drafted a letter to Spier in an exercise book and began on her diary the next day, probably at Spier’s advice and as part of her therapy. Little wonder then that the relationship with Spier was a major theme in her diaries.

For Etty, however, keeping a diary was useful for more than therapy alone; it also fit well with her literary ambitions. The diaries could later provide material for a novel, for example. In this context, it is also worth noting that her letters contain quotes from her diary. Although Spier’s patient, Etty also became his secretary and friend. Because Spier wished to remain faithful to Hertha Levi and because Etty already had a relationship with Wegerif, a certain distance was always present in the relationship between Etty and Spier, despite its importance to both. Spier had a very great influence on Etty’s spiritual development; he taught her how to deal with her depressive and egocentric bent and introduced her to the Bible and St. Augustine.

Etty had been reading other authors, such as Rilke and Dostoevsky, since the 1930s, but under Spier’s influence their work also took on deeper meaning for her. In the course of time, the relationship with Spier assumed a less central position in Etty’s life. When he died on 15 September 1942, therefore, she had developed enough to be able to assimilate his death with a certain ease—particularly because she realised as well the fate that would otherwise have awaited him as a Jew.

Westerbork

In the diaries, one can clearly see how the deepening anti-Jewish measures affected Etty Hillesum’s life; yet one also sees her determination to continue her spiritual and intellectual development. When she was expecting a summons to report to Camp Westerbork, she applied—at the recommendation of her brother Jaap—for a position with the Jewish Council. Through patronage, she received an appointment to the office on the Lijnbaansgracht (later the Oude Schans) on 15 July 1942. She performed her administrative duties for the Jewish Council with reluctance and had a negative opinion of the Council’s role. However, she found useful the work she was to do later for the department of “Social Welfare for People in Transit” at Westerbork, where she was transferred at her own request on 30 July 1942.

There it was that she met Joseph (Jopie) I. Vleeschhouwer and M. Osias Kormann, the two men who would go on to play a major role in her life. Her first stay at Westerbork did not last long; on 14 August 1942 she was back in Amsterdam. From there she left on 19 August to visit her parents for the last time in Deventer. Somewhere around 21 August she returned to Westerbork, but an illness forced her to go home on 5 December 1942. It was not until 5 June 1943 that she had recovered sufficiently to be allowed to return to Westerbork.

Unlike what one might expect, she was very keen to get back to the camp and resume her work so as to provide a bit of support for the people as they were preparing themselves for transport. It was for this reason that Etty Hillesum consistently turned down offers to go into hiding. She said that she wished to “share her people’s fate.”

Etty’s departure from Amsterdam on 6 June proved definitive, for on 5 July 1943 an end was put to the special status granted to personnel at the Westerbork section of the Jewish Council. Half of the personnel had to return to Amsterdam, while the other half became camp internees. Etty joined the latter group: she wished to remain with her father, mother, and brother Mischa, who had meanwhile been brought to Westerbork.

Etty’s parents had moved on 7 January 1943 to the Retiefstraat 11 hs in Amsterdam, after having first attempted to use doctor’s orders to circumvent their forced removal from Deventer. During the great raid of 20 and 21 June 1943, they were picked up—along with Mischa, who had come to live with them—and transported to Westerbork.

At the time this occurred, efforts were already being made to obtain special dispensation for Mischa on the grounds of his musical talent. The sisters Milli Ortmann and Grete Wendelgelst in particular were behind these efforts. Both Willem Mengelberg and Willem Andriessen wrote letters of recommendation, which have been preserved. These attempts proved fruitless, due to Mischa’s insistence that his parents also accompany him to the special camp at Barneveld. This was not allowed; Mischa did, however, receive a number of special privileges during his stay at Westerbork. When his mother wrote a letter to Rauter in which she asked for a few privileges as well, Rauter was enraged and on 6 September 1943, ordered the entire family to be immediately sent on transport. The camp commander at Westerbork, Gemmeker, interpreted this as an order to send Etty on the next day’s transport as well, despite the attempts by her contacts in the camp to protect her from this. On 7 September 1943, the Hillesum family left Westerbork.

Only Jaap Hillesum did not go with them; at the time, he was still in Amsterdam. He arrived in Westerbork in late September 1943. In February 1944 he was deported to Bergen-Belsen. When that camp was partially evacuated, he was placed on a train with other prisoners. After a journey full of deprivation and hardship, the train was finally liberated by Russian soldiers in April 1945. Like so many others, however, Jaap Hillesum did not survive the journey.

Etty’s father and mother either died during transport to Auschwitz or were gassed immediately upon arrival. The date of death given was 10 September 1943. According to the Red Cross, Etty died at Auschwitz on 30 November 1943. Her brother Mischa died on 31 March 1944, also at Auschwitz.

The diaries

Before her final departure for Westerbork, Etty gave her Amsterdam diaries to Maria Tuinzing, who had meanwhile come to live in the house on the Gabriel Metsustraat as well. Etty asked her to pass them along to the writer Klaas Smelik with the request that they be published if she did not return.

In 1946 or 1947, Maria Tuinzig turned over the exercise books and a bundle of letters to Klaas Smelik. His daughter Johanna (Jopie) Smelik then typed out sections of the diaries, but Klaas Smelik’s attempts to have the diaries published in the 1950s proved fruitless. Two letters Etty had written, in December 1942 and on 24 August 1943, concerning conditions in Westerbork, did get published.

They appeared in the autumn of 1943 in an illegal edition by David Koning at the recommendation of Etty’s friend Petra (Pim) Eldering. This edition, with a run of one hundred copies, was printed by B. H. Nooy of Purmerend under the title Drie brieven van den kunstschilder Johannes Baptiste van der Pluym (1843–1912) [Three Letters from the Painter Johannes Baptiste van der Pluym (1843–1912)]. The two letters were preceded by a foreword with a biography of the artist and followed by a third letter, both written by David Koning to camouflage the true contents. The revenues from the publication were used to provide assistance to Jews in hiding. These letters have since been republished on several occasions.

In late 1979, Klaas A.D. Smelik, now director of the Etty Hillesum Research Centre, approached the publisher J. G. Gaarlandt with a request to publish the diaries left to him by his father, Klaas Smelik. This resulted in the publication in 1981 of Het verstoorde leven (An Interrupted Life) and in 1986 of all Hillesum’s known writings in Dutch, later translated in English. An Interrupted Life was republished in 1999 by Persephone Books.

Dorothy Day

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia and other web sites

(Dorothy Day in 1916 at the age of 19)

(Dorothy Day in 1916 at the age of 19)

Dorothy Day, Obl.S.B. (November 8, 1897 – November 29, 1980) was an American journalist, social activist, and devoutCatholic convert; she advocated the Catholic economic theory of distributism. Day “believed all states were inherently totalitarian,” and was considered to be an anarchist and did not hesitate to use the term.

In the 1930s, Day worked closely with fellow activist Peter Maurin to establish the Catholic Worker movement, a nonviolent, pacifist movement that continues to combine direct aid for the poor and homeless with nonviolent direct action on their behalf.

The cause for Day’s canonization is open in the Catholic Church, and she is thus formally referred to as a Servant of God.

Early life

Dorothy Day was born in the Brooklyn Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, and raised in San Francisco andChicago. She was born into a family described by one biographer as “solid, patriotic, and middle class.” Her father, John Day, was a Tennessee native of Scots-Irish heritage, while her mother, Grace Satterlee, a native of upstate New York, was of English ancestry.

Her parents were married in an Episcopalian church located in Greenwich Village, a neighborhood where Day would spend much of her young adulthood.

In 1904, her father, who was a sports writer, took a position with a newspaper in San Francisco. They lived in Oakland, California, until the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 destroyed the newspaper’s facilities and her father lost his job. The earthquake’s devastation and how people helped homeless victims became strongly ingrained in the young Dorothy’s memory. The family then relocated to Chicago.

Day was an avid reader as a child. She was particularly fond of Upton Sinclair, Jack London, and hagiographies of Catholic saints. She had also read Peter Kropotkin, an advocate of anarchist communism, which, along with these others, influenced her ideas in how society could be organized.

In 1914, Day attended the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign on a scholarship, but dropped out after two years and moved to New York City.

Day was a reluctant scholar. Her reading was chiefly in a radical social direction. She avoided campus social life and insisted on supporting herself rather than live on money from her father, a characteristic she was to maintain for the rest of her life, to the point of buying all her clothing and shoes from discount stores to save money.

Settling on the Lower East Side, she worked on the staffs of Socialist publications (The Liberator, The Masses, The Call), though she “smilingly explained to impatient socialists that she was ‘a pacifist even in the class war.'”

She also engaged in anti-war and women’s suffrage protests, spent several months in Greenwich Village, where she became close to Eugene O’Neill, and later joined the Industrial Workers of the World (‘Wobblies’).

She rejoiced at the success of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, as she relates in “From Union Square to Rome”.” She maintained friendships with such prominent American Communists as Mike Gold, Anna Louise Strong, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (who became the head of the Communist Party USA), all of whom she praised and eulogized in the Catholic Worker. In the November 1949 issue, she described herself as an “ex-Communist,” and in the January 1970 issue she declared that the Catholic Worker is “a revolutionary headquarters rather than a Bowery mission, as most newspapers like to picture us.”

Spiritual awakening

Roots

Dorothy’s parents were nominal Christians, rarely attending church. As a young child, she showed a marked religious streak, though, reading the Bible frequently. When she was ten she started to attend an Episcopalian church, after its rector had convinced their mother to let the Day brothers join the church choir; she became taken with the liturgy and its music. She studied the catechism and was baptized and confirmed in the church. Despite this she saw herself as agnostic.

Initially Day lived a bohemian life; her short marriage to Berkeley Tobey occurred “on the rebound” after an “unhappy love affair with a tough ex-newspaperman named Lionel Moise” and an abortion, which she later described in her semi-autobiographical novel, The Eleventh Virgin ISBN 978-0983760511 (1924)—a book she later regretted writing.

The sale of the movie rights to the novel enabled her to settle down, using the proceeds to buy a beach cottage on Staten Island, New York. She lived there with Forster Batterham, a biologist with whom she shared a deep interest in social activism. It was a time of idyllic peace for her, as she shared the company of good friends and enjoyed the beauty of nature, which Batterham helped her to appreciate.

During this period, however, Day began a time of spiritual awakening which would lead her to embrace Catholicism. She had picked up a rosary in New Orleans during the course of her many moves around the country and started to recite the canticlesshe had learned at her childhood church in Chicago. She began to attend Mass on Sundays at the nearby Catholic church.

This growing interest in religion became a continuing source of conflict and division between Day and Batterham, who had a deep aversion to religion. Unexpectedly, Day found that she was pregnant. As her partner opposed having children, this became another source of conflict. Despite his opposition, she resolved to have her child and to have it baptized, to give the child a spiritual foundation she had lost herself. In all her travels, Day had identified with the people of the working class, and everywhere she went the majority had been Catholics. Thus, she chose to give her allegiance to that faith.

After the birth of her daughter, Tamar Teresa (1926–2008), Day chanced to meet Sister Aloysius, S.C., a Catholic Religious Sister, walking down her street. She asked the Sister how she could have the child baptized. Sister Aloysius helped her, requiring Day to memorize the Baltimore Catechism for this. Tamar’s baptism was opposed by Batterham, who continued to live with Day and the child in Staten Island when he was not working in Manhattan. Day loved him deeply and respected him for his stand on social causes, putting off any move to join the Church because she did not want to lose him. This tension, she reported, led to illness and resulted in a nervous condition.

Conversion

Exasperated, Day broke up with Batterham; she refused to take him back when he returned after an emotional “explosion” had occurred. She then went immediately to Sister Aloysius to arrange for admission to the Catholic Church.

This took place in December 1927, with her conditional baptism (due to her prior baptism in the Episcopalian Church) at Our Lady Help of Christians Parish on Staten Island. In her 1952 autobiography, The Long Loneliness, Day recalled that immediately after her baptism she made her first Confession and the following day she made her First Communion.

In the summer of 1929, Day decided to leave New York temporarily, partly to put the situation with Batterham behind her, and also to accept work as a screen writer in Hollywood. She moved with Tamar to Los Angeles. She returned to New York just as the effects of the Great Depression were beginning to be felt. Later, Day began writing for Catholic publications, such as Commonweal[22] and America on the events of that situation around the country. She began to feel separated from the protesters in the streets, feeling a lack of leadership from her new faith.

In the early 1940s she became a Benedictine oblate, which gave her a spiritual practice and connection that sustained her throughout the rest of her life. As described in her letters in “All the Way to Heaven,” she left the Benedictines for a time to consider joining the Fraternity of Jesu Caritas, which was inspired by the example of Charles de Foucauld. Day felt unwelcome there and disagreed with how meetings were run. When she decided to return to the Benedictines and withdraw herself as a candidate in the Fraternity, she wrote to a friend, “I just wanted to let you know that I feel even closer to it all, tho it is not possible for me to be a recognized ‘Little Sister,’ or formally a part of it”.

The Catholic Worker Movement

Peter Maurin

In 1932, Day met Peter Maurin, the man she would always credit as the founder of the movement with which she is identified. Maurin, a French immigrant and something of a vagabond, claimed to be from a family which had occupied the same farm which their distant ancestor had received as a bonus for service in the Roman army. He had entered the Brothers of the Christian Schools in his native France, before emigrating, first to Canada, then to the United States.

Despite his lack of formal credentials, Maurin was a man of deep intellect and decidedly strong views. He had a vision of social justice and its connection with the poor which was partly inspired by St. Francis of Assisi. He had a vision of action based on a sharing of ideas and subsequent action by the poor themselves. Maurin was deeply versed in the writings of the Church Fathersand the papal documents on social matters which had been issued by Pope Leo XIII and his successors. Through this knowledge, Maurin provided Day with the grounding in Catholic theology of the need for social action both felt. Years later Day described how Maurin also broadened her knowledge by bringing “a digest of the writings of Kropotkin one day, calling my attention especially toFields, Factories, and Workshops; Day observed: “I was familiar with Kropotkin only through his Memoirs of a Revolutionist, which had originally run serially in the Atlantic Monthly. (Oh, far-[past] day of American freedom, when Karl Marx could write for the morning Tribune in New York, and Kropotkin could not only be published in the Atlantic, but be received as a guest into the homes of New England Unitarians, and in Jane Addams’ Hull House in Chicago!)”

The Catholic Worker

The Catholic Worker movement started with the publication of the Catholic Worker, first issued on May 1, 1933. It was established to promote Catholic social teaching in the depths of the Great Depression and to stake out a neutral, pacifist position in the war-torn 1930s. (See the Catholic Worker: The Aims and Means of the Catholic Worker.) This grew into a “house of hospitality” in the slums of New York City and then a series of farms for people to live together communally.

The movement quickly spread to other cities in the United States and to Canada and the United Kingdom; more than 30 independent but affiliated CW communities had been founded by 1941. Well over 100 communities exist today, including several in Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada,Germany, the Netherlands, the Republic of Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand, and Sweden.

Fame

By the 1960s, Day was embraced by a significant number of Catholics, while at the same time, she earned the praise of counterculture leaders such as Abbie Hoffman, who characterized her as the first hippie, a description of which Day approved, though there is some evidence which indicates Day might not always have taken a positive view of the hippie movement.

Although Day had written passionately about women’s rights, free love, and birth control in the 1910s, she opposed the sexual revolution of the 1960s and beyond, saying she had seen the ill effects of a similar sexual revolution in the 1920s. Day had a progressive attitude toward social and economic rights, alloyed with a very orthodox and traditional sense of Catholic morality and piety. A daily communicant, Day was unable to prevent the irregularities that occurred at the Tivoli Catholic Worker Farm. In her diary she relates the criticisms of Stanley Vishnewski, then declares, “But I have no power to control smoking of pot, for instance, or sexual promiscuity, or solitary sins.”

Her devotion to her church was neither conventional nor unquestioning, however. She alienated many U.S. Catholics (including some clerical leaders) with her condemnation of the authoritarian Falangist Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War; and, possibly in response to her criticism of Cardinal Francis Spellman, she came under pressure by the Archdiocese of New York in 1951 to change the name of her newspaper, “because the word Catholic implies an official church connection when such was not the case.”

The newspaper’s name was not changed.

Awards

In 1971, Day was awarded the Pacem in Terris Award of the Interracial Council of the Catholic Diocese of Davenport, Iowa. It was named after the 1963 encyclical by Pope John XXIII which calls upon all people of good will to secure peace among all nations. Pacem in Terris is Latin for “Peace on Earth.” Day was accorded many other honors in her last decade of life, including the Laetare Medal from the University of Notre Dame in 1972.

Later life and death

Despite suffering from poor health, Day traveled around the world to preach the power of God’s love and the way of pacifism. She went to India, where she met Mother Teresa and saw her work. In 1971, with the financial support of Corliss Lamont, who she described as a “‘pinko’ millionaire who lived modestly and helped the [Communist Party USA],” Day made a trip to the Soviet Union as part of a “peace pilgrimage.”

She met with three members of the Writers’ Union to defend Alexander Solzhenitsyn against charges that he “sold out” the USSR; Day informed her readers that “Solzhenitsin lives in poverty and has been expelled from the Writers Union and cannot be published in his own country. He is harassed continually, and recently his small cottage in the country has been vandalized and papers destroyed, and a friend of his who went to bring some of his papers to him was seized and beaten. The letter Solzhenitsin wrote protesting this was widely printed in the west, and I was happy to see as a result a letter of apology by the authorities in Moscow, saying that it was the local police who had acted so violently.”

The travel restrictions on tourists did not prevent Day from going to the Kremlin, and she reported: “I was moved to see the names of the Americans, Ruthenberg and Bill Haywood, on the Kremlin Wall in Roman letters, and the name of Jack Reed (with whom I worked on the old Masses), in Cyrillac characters in a flower-covered grave…. I felt that my former roommate, at the University of Illinois, Rayna Prohme, should have had a flower-bedecked grave along the Kremlin wall also. She had edited a paper in Hankow, had accompanied Madame Sun Yat Sen to Moscow when Chiang Kai Shek had taken over the Communist dominated city, and was preparing to continue her work as a dedicated Communist when she died in Moscow.”

She joined Cesar Chavez in his efforts to provide justice for farm laborers in the fields of California. There, at the age of 75, she was arrested with other protesters and spent ten days in jail. From 1972 to 1978 she was a part-time resident of the now-demolished Spanish Camp community in the Annadale section of Staten Island.

Day gave her final public appearance at the Eucharistic Congress held on August 6, 1976, in the City of Philadelphia to honor the Bicentennial of the United States. She spoke on the love God has for humanity and the need to spread that love throughout creation. Day characteristically tied in her message to the anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on that day.

Shortly after this, Day suffered a heart attack. She died on November 29, 1980, at Maryhouse in New York City.

Day was buried in the Cemetery of the Resurrection on Staten Island, just a few blocks from the location of the beachside cottage where she first became interested in Catholicism.

Cause for sainthood

A proposal for Day’s canonization was put forth publicly by the Claretian Missionaries in 1983. At the request of Cardinal John J. O’Connor, made as head of the diocese in which she lived, in March 2000 Pope John Paul II granted the Archdiocese of New York permission to open this cause, thereby officially allowing her to be called a “Servant of God” in the eyes of the Catholic Church.

In keeping with canon law, the Archdiocese of New York then submitted this cause for endorsement by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, the national organization of the bishop of the country. In November 2012, during the course of a semi-annual meeting, and at the urging of the current Archbishop of New York, Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan, President of the organization, the Conference formally endorsed this cause.

In introducing this “consultative” item, Cardinal Dolan gave his fellow bishops the following “clarification”: “you’re not being asked to indicate whether or not you consent to the cause–I hope you do–but if you have any objections, there’ll be chances for you to express those during the cause. What I’m seeking your opinion about is the opportuneness of advancing the cause on the local level.”

In the Episcopal Church, Dorothy Day is listed as a person “worthy of commemoration” in the liturgical calendar but for whom not enough time has elapsed since her death; the current guidelines of the Episcopal Church for an official commemoration in the calendar include waiting fifty years after the death of the one being commemorated. “Local and regional commemorations” are encouraged.

Facebook Comments