The month of April 2012 saw the Vatican and Beijing sharpen their contrasting strategies towards the Catholic Church and its more than 12 million members in the People’s Republic of China.

Three specific events took place around the same time in that month that clearly illustrated the opposing strategies: (1) two new bishops were ordained with the approval of Rome and Beijing on April 19 and 25; (2) but Beijing insisted on having bishops not in good standing with Rome participate in each ceremony; and (3) the Commission for China held its annual plenary meeting at the Vatican (April 23-25). The Commission set out with determination to eliminate the ambiguities and divisions that Beijing seeks to insert into such key events in the life of the Church as the ordinations of bishops.

Since the Communist Party came to power in China in 1949, it has always sought to control all religious organizations, including the Catholic Church. In 1957, it established the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association (CPA) to govern the life of the Catholic Church and make it independent of Rome. That body still exercises nation-wide power over bishops, priests and Church life in general; it does so under the direction of higher political bodies including the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA) and the United Front.

In 1958, the CPA began ordaining bishops without papal approval, and still today is ready to do the same whenever this serves Beijing’s strategic goals. Nevertheless, it is encountering increasing resistance from bishops and sometimes, though rarely, from candidates to be bishops, and so — as happened in June and July 2011 — it has to resort to a mixture of financial incentives, political pressure and physical force to get bishops to comply with its agenda.

The Holy See, on the other hand, considers the CPA as a body alien to the constitution of the Church, and does not recognize it. It insists, moreover, that a candidate to be bishop has to have the Pope’s approval prior to ordination. Last year, it showed that it is now prepared to excommunicate those who present themselves for ordination without that approval.

Beijing knows well that the overwhelming majority of the faithful and of the bishops want to be in union with the Pope. The statistics speak for themselves: at the end of 2011, there were 117 bishops in mainland China and only seven were illegitimate, that is, ordained without papal approval. By April 2012, less than a dozen other bishops were not in full communion with the Pope because they had participated in two illegitimate ordinations in June-

July 2011, and had incurred automatic penalties. Around a dozen or so more had also participated in those illegitimate ordinations, but they had already explained their actions to the Pope and requested his pardon, which was granted. Thus, by early May 2012, almost 90% of all the mainland bishops were in full communion with the Holy See.

While Rome has worked hard to ensure this communion, Beijing has striven with equal determination to prevent this by seeking to increase the number of bishops not in communion with the Pope. It has done so in three ways: first, by ordaining bishops without the Pope’s approval; second, by getting those illegitimate bishops to participate in legitimate ordinations; and, third, by getting legitimate bishops to participate in illicit ordinations.

Since June 2011, Bejing has used all three ways in pursuit of its long-standing goal to build a national Church independent of Rome: it organized the ordinations of two bishops without the Pope’s approval on June 29 (in Leshan) and July 14, 2011 (in Shantou), and it arranged three ordinations approved by the Pope on November 30, 2011 (in Yibin), and on April 19 (in Nanchong) and April 25 (in Hunan) this year.

But in all five ordinations, Beijing sought to compromise the communion of bishops with the Pope by having those in good standing with Rome participate together with those who are not. In all, some 20 bishops participated.

Beijing’s strategy of “mixing” legitimate with illegitimate bishops in these ceremonies was denounced by Cardinal John Tong Hon of Hong Kong when he spoke to journalists on April 22, after taking possession of his titular church in Rome.

“We must always safeguard our principles,” he said. There are two important requirements for the ordination of a Catholic bishop, he explained: first, “the candidate to be bishop should be approved by the Holy Father to safeguard the unity of the Church,” and, second, “all the bishops involved with the consecration (of a new bishop) must not only be valid, they must also be legitimate” — in other words, they must be in communion with the Pope.

“The mixing of the illegitimate with the legitimate is wrong, and should not be allowed,” Cardinal Tong stated. “I hope this won’t happen anymore in the future, and that anyone who committed the offense on this occasion repents and submits a request to the Holy Father for pardon,” he said.

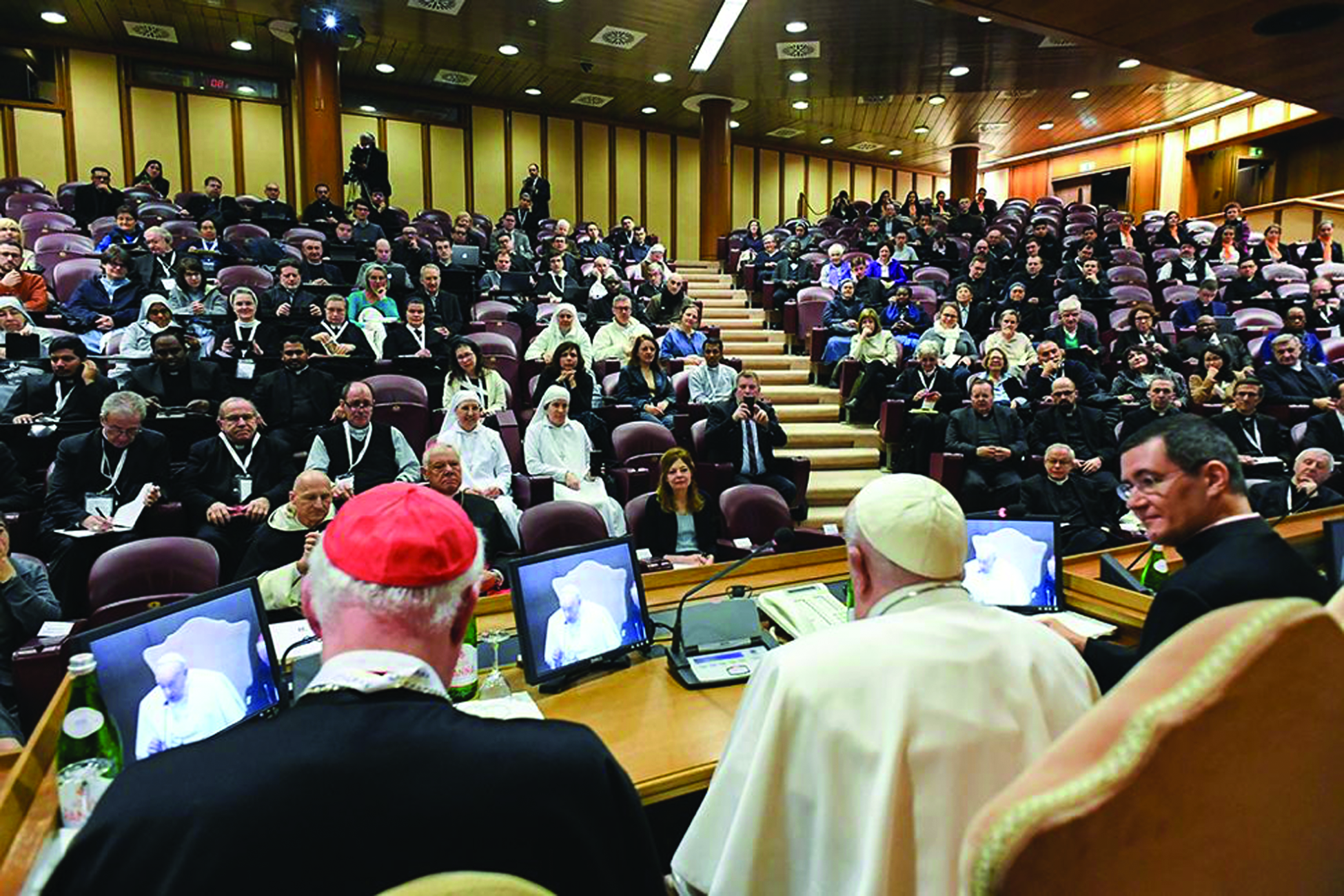

Next day, Cardinal Tong participated in the fifth annual plenary meeting of the Commission for China, together with Chinese bishops from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan, and two dozen senior Vatican officials and representatives of religious orders with links to China. Pope Benedict had set up the Commission in 2007 to study the issues of major importance for the life and mission of the Church in China and to advise him on these.

The plenary meeting at the Vatican focused on the formation of the laity in China and, among other matters, discussed Beijing’s strategy of “mixing” legitimate and illegitimate bishops in episcopal ordinations which creates confusion in the Catholic community in China.

Since the Commission is an advisory body, its conclusions become part of Vatican policy when the Holy See makes them its own, as happened in April when it issued a statement approved by Pope Benedict. That text set out, among other things, to eliminate the ambiguities regarding the bishop’s role in the Church, ambiguities that have been introduced by the CPA and other state entities.

“The Church needs good bishops,” the communiqué stated. It reminded China’s bishops that it is “from Christ, through the Church” that “they receive their task and authority.” In other words, their “task and authority” do not come from Beijing’s government or its entities, and they “exercise” this “in union with the Roman Pontiff and with all the bishops throughout the world.”

Then going to the heart of the problem, the statement re-affirmed that “the claim” of the CPA and the bishops’ conference created by the Chinese government “to place themselves above the bishops and to guide the life of the ecclesial community” does not correspond to Catholic doctrine. Pope Benedict had already made this clear in his 2007 Letter to Catholics in China.

The Holy See’s statement reminded mainland Catholics — and indirectly the government — that the Pope’s 2007 “instructions” are still operative and provide “direction” and therefore “it is important to observe them.” By following his instructions, it said, “the face of the Church” can shine forth clearly, without ambiguity or confusion.

Since the confusion and ambiguity is created by bishops or candidates to be bishops who follow instructions from the CPA rather than from the Pope, the statement focused on those Chinese “clerics” who have obscured (“obfuscated”) this clear Church teaching by doing this. It mentions two distinct groups: illegitimate bishops and legitimate bishops.

The first group “obfuscates” the Church’s teaching because they have been ordained as bishops “illegitimately,” that is, without the Pope’s approval, and they have subsequently “carried out acts of jurisdiction” or “administered the sacraments.”

By doing so, the Holy See said, “they usurp a power that the Church has not conferred upon them.” Furthermore, by participating — as some did in November 2011 and April 2012 — in episcopal ordinations that had the Pope’s approval, they have “aggravated” their personal situation before Church law, “disturbed the faithful” and “often violated the consciences of the priests and lay faithful who were involved.”

As for the second category of clerics who “obfuscate” the Church’s doctrine, the Holy See said these are “legitimate bishops” who have participated in “illegitimate episcopal ordinations,” that is, ordinations of bishops who lack the papal mandate. It revealed that “many” of these bishops “have since clarified their position” and have asked and received pardon from Benedict XVI. But other bishops “who also took part” in those illegitimate ordinations “have not yet made this clarification,” the statement said, and it “encouraged” them “to do so as soon as possible.”

The Holy See’s statement went on to remind all bishops and priests in China that “evangelization cannot be achieved by sacrificing essential elements of the Catholic faith and discipline.” This reminder was read as a response to the CPA and other Chinese officials who seek to justify illegitimate ordinations on the grounds that the Church needs bishops to promote evangelization.

Furthermore, the Holy See is well aware that China’s bishops need the support of their priests, consecrated men and women, and lay faithful to help them resist pressure from the CPA and other state bodies, and to act in accordance with Catholic doctrine and discipline. For this reason, and others too, it has — with the help of the China Commission — emphasized the vital importance of good formation for the more than 12 million laity (over 6 million “underground”), the 5000 consecrated women (1,600 “underground”) and the 3,200 priests (1,300 “underground”) in mainland China.

Formation is the challenge that lies ahead for the Church in China. It is the way to build greater unity in that Church, and to overcome the divisions forced on that one Church by the CPA and Beijing.

It is the way to foster understanding and reconciliation between the “underground” and “open” (state-recognized) Catholic communities that live side by side on the mainland.

It is one of the keys to the new evangelization of the Chinese people.

Facebook Comments