Lectio magistralis of Cardinal Pietro Parolin on how to build peace with diplomacy. A new “office for pontifical mediation”? A surprising offer of dialogue with Saudi Arabia.

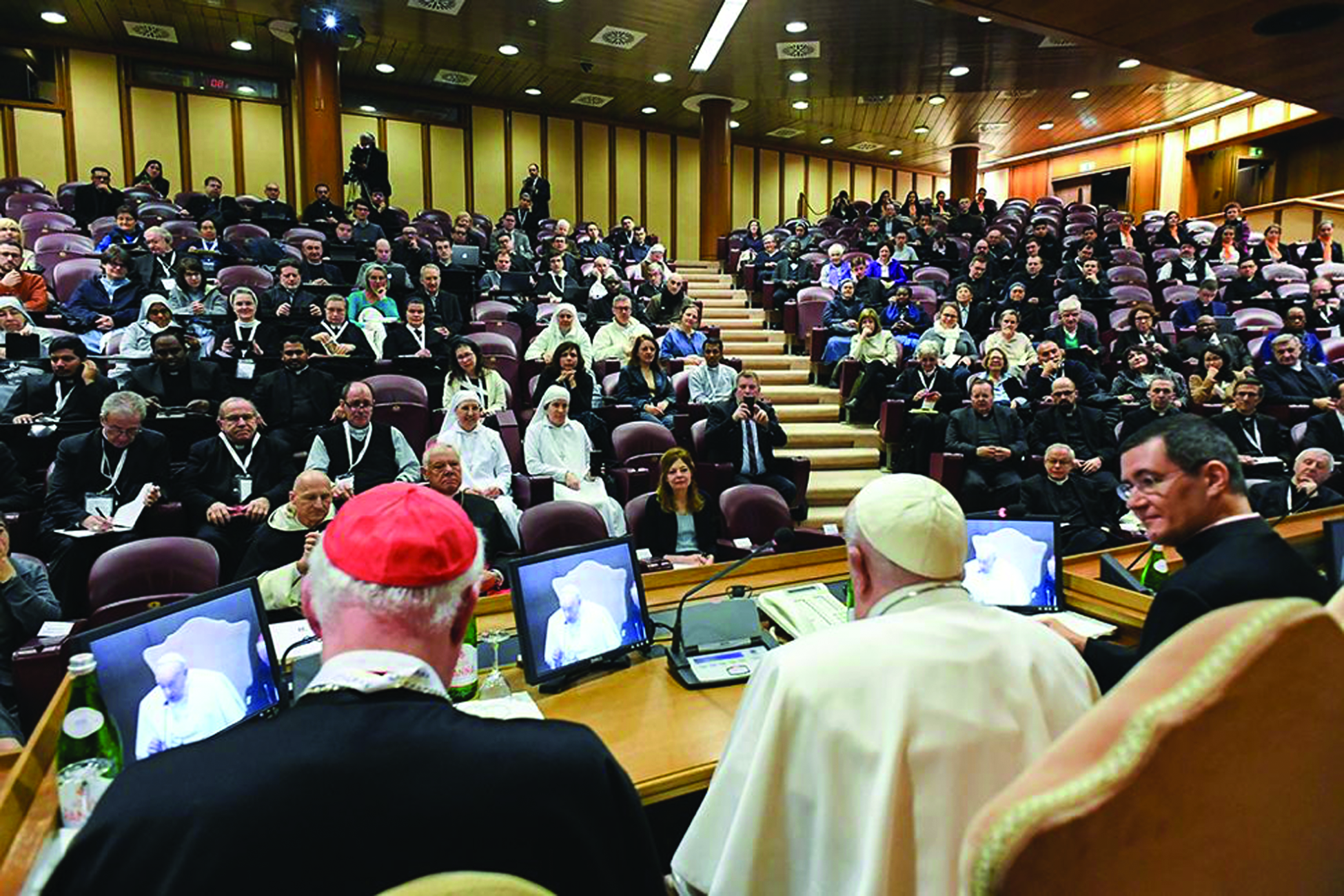

For one day, Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Parolin literally rose to the throne. He did so on Wednesday, March 11 at the Pontifical Gregorian University, where he delivered a lectio magistralis on the theme most distinctly his own: the diplomacy of the Holy See.

The complete text of his lecture was immediately released by the Vatican press office (in Italian), and excerpts in English are reproduced below.

In his talk, Parolin proposes the permanent constitution, within the Secretariat of State, of an “office for pontifical mediation,” at the service of initiatives like that secretly undertaken by the authorities of the Church for the re-establishment of relations between Cuba and United States.

Secrecy, discretion, prudence — these are three of the virtues that Parolin assigns to the good diplomat. And that he himself exercises with conviction, as demonstrated by the complete discretion with which he defends the current approaches of Vatican diplomacy toward one of the most problematic of dialogue partners, China, even at the cost of undergoing criticism from such a prominent representative of the Chinese Church itself as Cardinal Joseph Zen Ze-kiun, who says that he fears that China is seeking “unconditional surrender” from the Vatican.

One point on which Parolin expresses hopes for new developments concerns recourse to force.

To the “ius ad bellum,” “ius in bello,” and “ius contra bellum”—meaning the rules that justify the opening of war, impose limits on its conduct, and aim at preventing it — the cardinal proposes adding a “ius post bellum” that would not be limited to establishing relations between victors and vanquished at the end of the conflict (and here he cites, removing them from their context, the words of Pope Francis in February on the war in Ukraine that had deeply embittered the bishops of that country), but would extend to reconciliation among the parties, to the return of refugees, to the re-establishment of institutions, to the revival of the economy, to the protection of the artistic, cultural, and religious patrimony.

Another point on which Parolin expresses hope concerns the means of disarming aggressors.

In addition to armed humanitarian intervention and the duty to protect peoples that were insisted upon by, he recalls, John Paul II and Benedict XVI, the cardinal proposes “the search for additional tools” to oppose even new kinds of aggressors such as the “extraterritorial” terrorism now in action, in particular with the empowerment of a transnational judicial body.

With regard to religious freedom, Parolin recalls how the “ten principles” of the 1975 Helsinki Accords still need to be applied, all the more so at a “moment in which it is well documented that Christians are among the most discriminated against and there continue to be laws, decisions, and behaviors that are intolerant toward the Catholic Church and other Christian communities.”

And for the sake of “structuring dialogue among religions on the basis of the institutions and norms of international law,” the cardinal points to the example of an intergovernmental organization headquartered in Vienna, the International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue, abbreviated KAICIID.

But Parolin does not mention that the first two letters of the acronym stand for King Abdullah, referring to the monarchy of Saudi Arabia, which is the founder of the organization together with Austria and Spain, with the Holy See as a “founding observer.”

Nor does he seem to take into account the fact that last February the government of Vienna threatened Saudi Arabia with the closure of the center’s offices, after the human rights activist Raif Badawy was given a sentence of a thousand lashes and ten years in prison, the latest of many proofs of the illiberalism of that kingdom and of the extremism with which it applies the laws of the Quran.

Saudi Arabia responded to Austria’s threat by threatening in turn to remove from Vienna the headquarters of OPEC, the organization of oil producers of which it is the most influential member, rejecting all outside interference in its affairs and claiming to be “among the foremost countries” in upholding human rights, “albeit in accordance with Quranic law.”

The Holy See’s observer at the KAICIID is Fr. Miguel Angel Ayuso Guixot, secretary of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue headed by Cardinal Jean-Louis Tauran.

The unexpected citation of the KAICIID made by Parolin in his “lectio magistralis” can be seen as an outstanding example of Parolin’s diplomatic style, alien to any rupture even with the most intractable dialogue partners.

Sandro Magister, 71, is an Italian journalist who writes for the weekly Italian magazine l’Espresso on the Catholic Church and the Vatican. He has written two books on the political history of the Italian Church: La politica vaticana e l’Italia 1943-1978 [“Vatican Politics and Italy 1943-1978”], Rome, 1979, and La Chiesa extraparlamentare. Il trionfo del pulpito [“Extraparliamentary Church: The Triumph of the Pulpit”], Naples, 2001. In 2008, 2009, and 2010, he oversaw the publication of three volumes with the homilies of Benedict XVI from the corresponding liturgical years, published by Libri Scheiwiller. His articles are posted on the internet at the website: https://chiesa.espresso.repubblica.it.

Facebook Comments